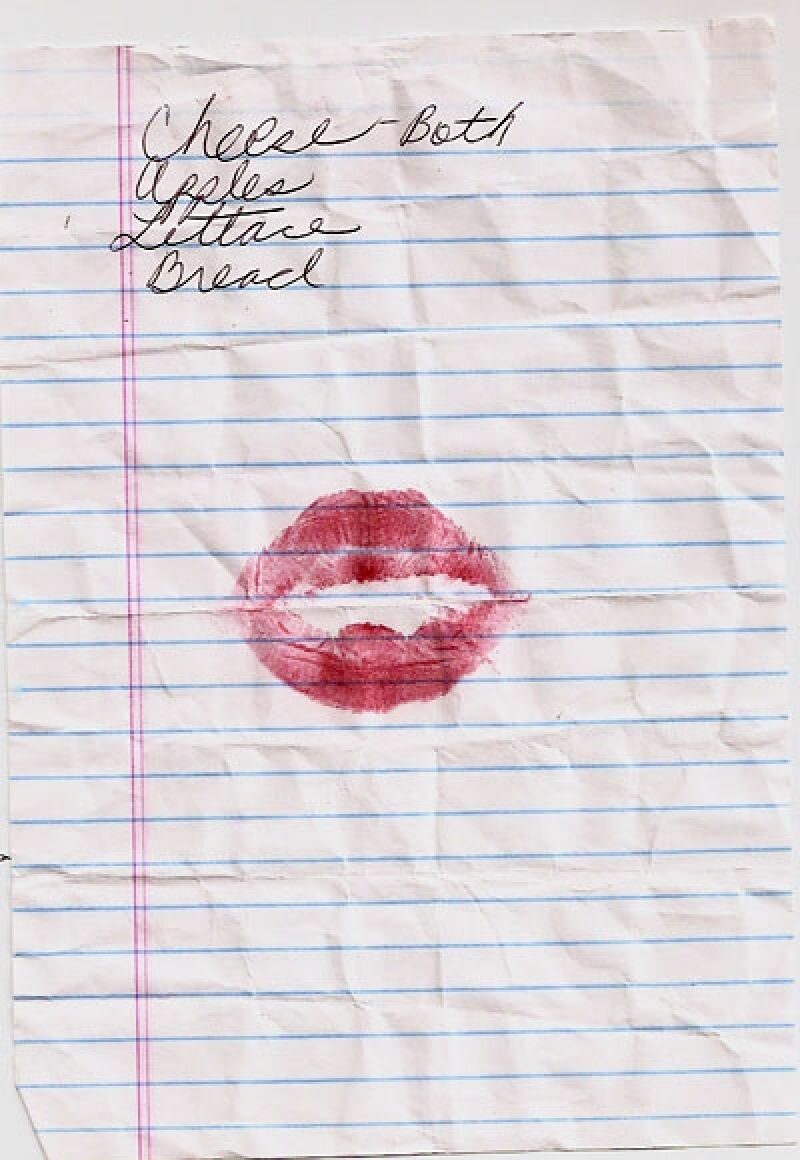

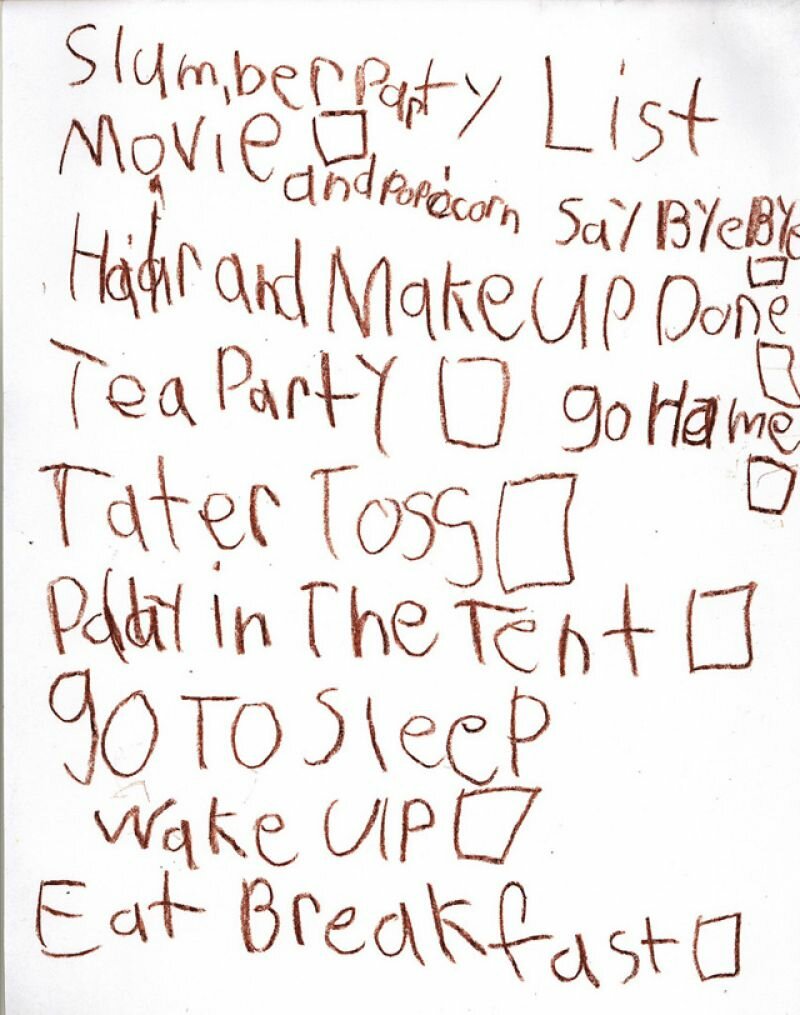

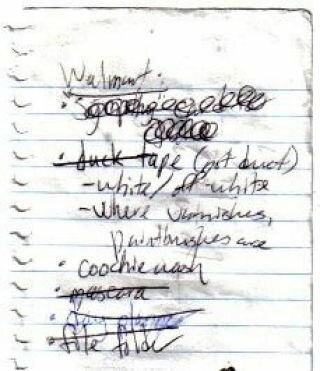

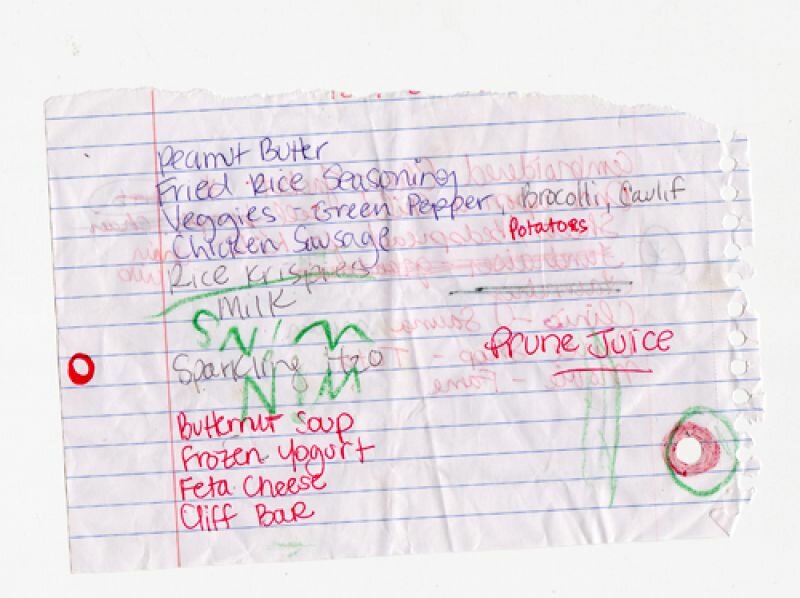

As entries, strike-throughs, spelling mistakes, re-entries, question marks, lists within lists, bullet-points, dashes, personalised bullet-points, squares, asterisks, circled entries, bold entries, ambitious entries and already-done entries are scattered across the page, the mind moves quicker than the pen to create this masterpiece in its initial form. Margins, the bottom of the list or the space in between the lines are an opportunity to add information that could not keep up with the mind or that were simply forgotten. At times, these secondary entries will appear in a different colour where an alternative writing tool has had to be used.

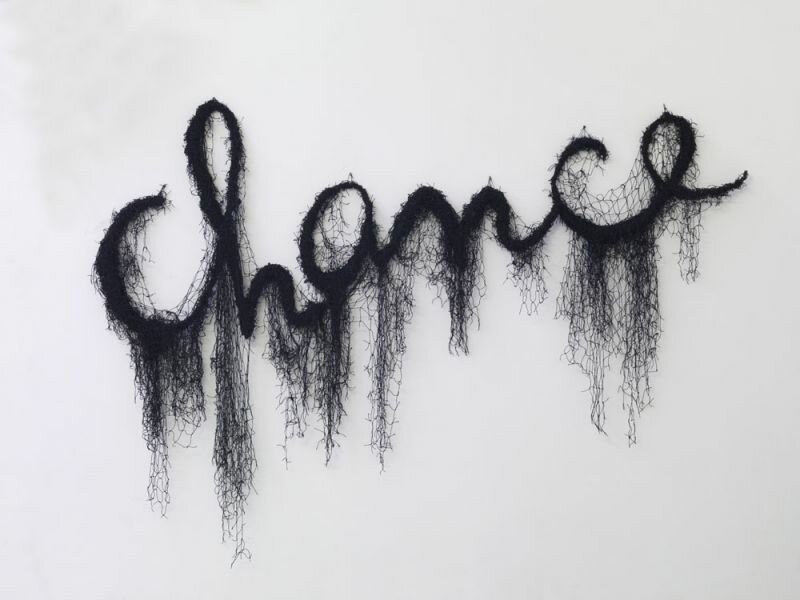

The creator of a list has no intention to design their thoughts but merely to order them visually in tangible form. The back of a card, an old envelope, some scrap paper, a notebook, a smart phone, a saved email draft, a train ticket or a post-it note provide the canvas for this mind montage to be drawn out.

The activity of list-making is both common to all yet entirely individualistic.There is a sense of urgency attached to something that is created on-the-go or in between activities and maybe it is the extent of this pressure that when making a list, normal writing conventions are ignored. Baselines are misused, words are written across them rather than on them; the ascenders on letters become muted; the descenders have added flamboyancy and the margins are no longer a no-go area for words but a place to fill with words, additional thoughts, numbers, sketches and question marks.

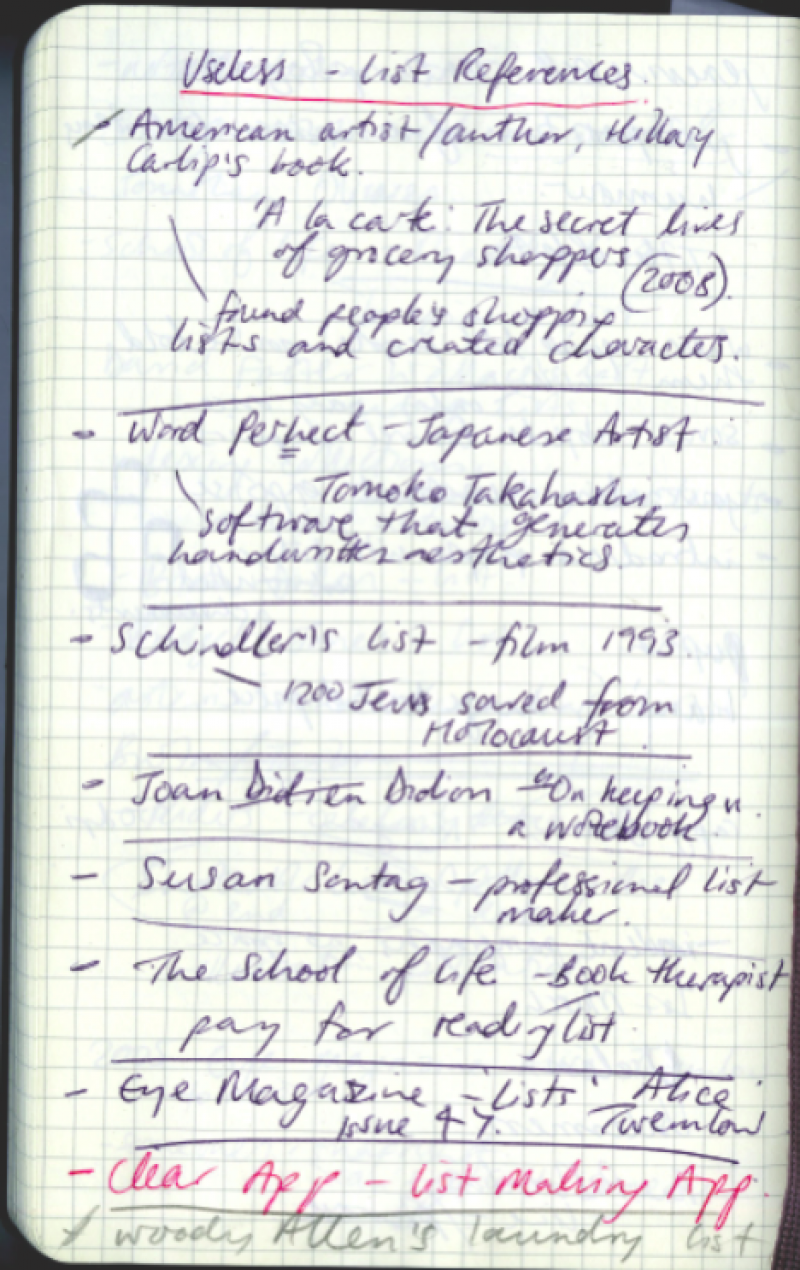

In a moment’s pause, a second thought is given to putting these thoughts into better order or form, perhaps in order of priority or alphabetically.This can be done at a later date. Sometimes, a complete re-draft of the list might be necessary. If it is a list of that type it can be prepared to make sense to others. It is at this point a design element might be added: colour coding, font selection, margin widths and line lengths.

There is an unspoken hierarchy to the various forms of lists that surround us in our daily lives.Train times, shopping lists, gift lists, hate lists, wish lists, to-do lists, today’s food specials, contents pages, registers, stock lists, missing lists, menus and guest lists. The different forms of lists are matched and paired with a tried and tested format. Registers are done alphabetically; shopping lists by memory, train times chronologically etc.

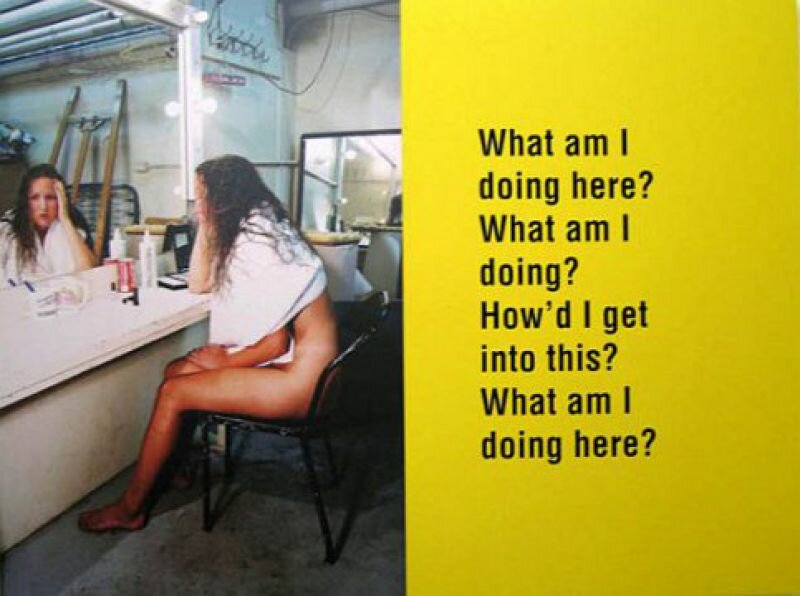

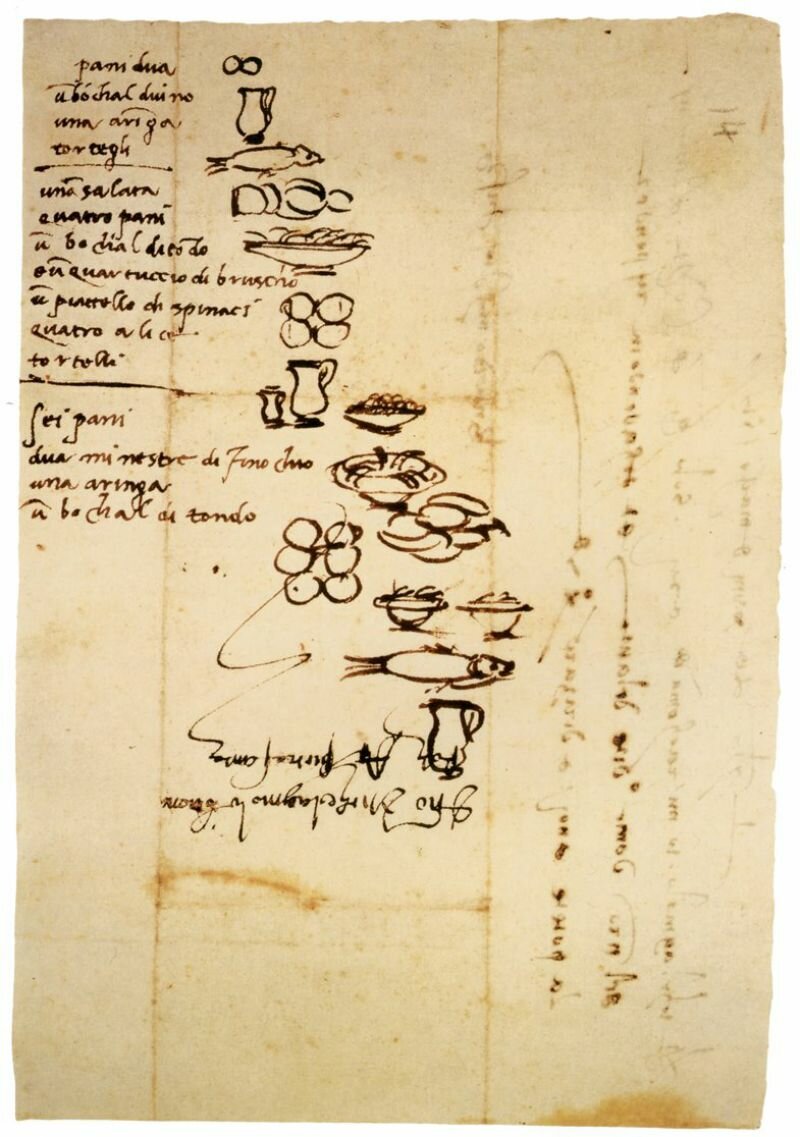

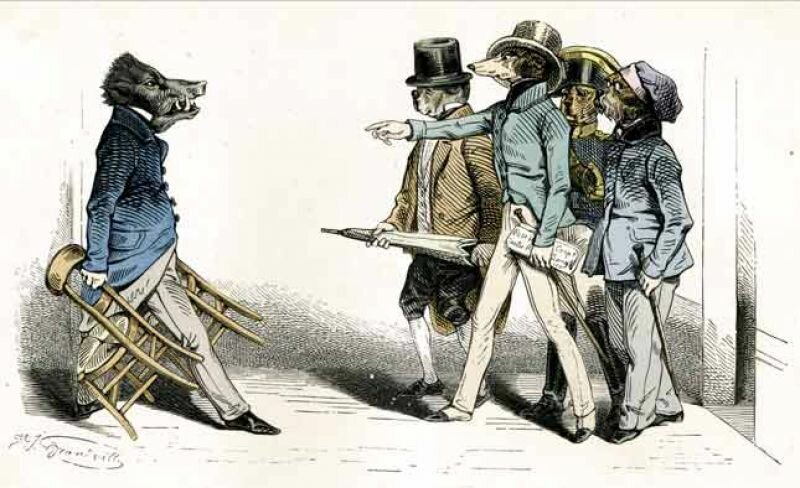

When a list finds itself in the hands of someone other than its author, different aspects of it might be scrutinised. The graphologist looks at the space between the lines and the curves or flicks of the letters, the size of the capital letters, the margins around the texts and the slant of the handwriting. The artist dreams up the story that precedes the list and what might follow. The curious looks around to find its owner. And others disregard it.

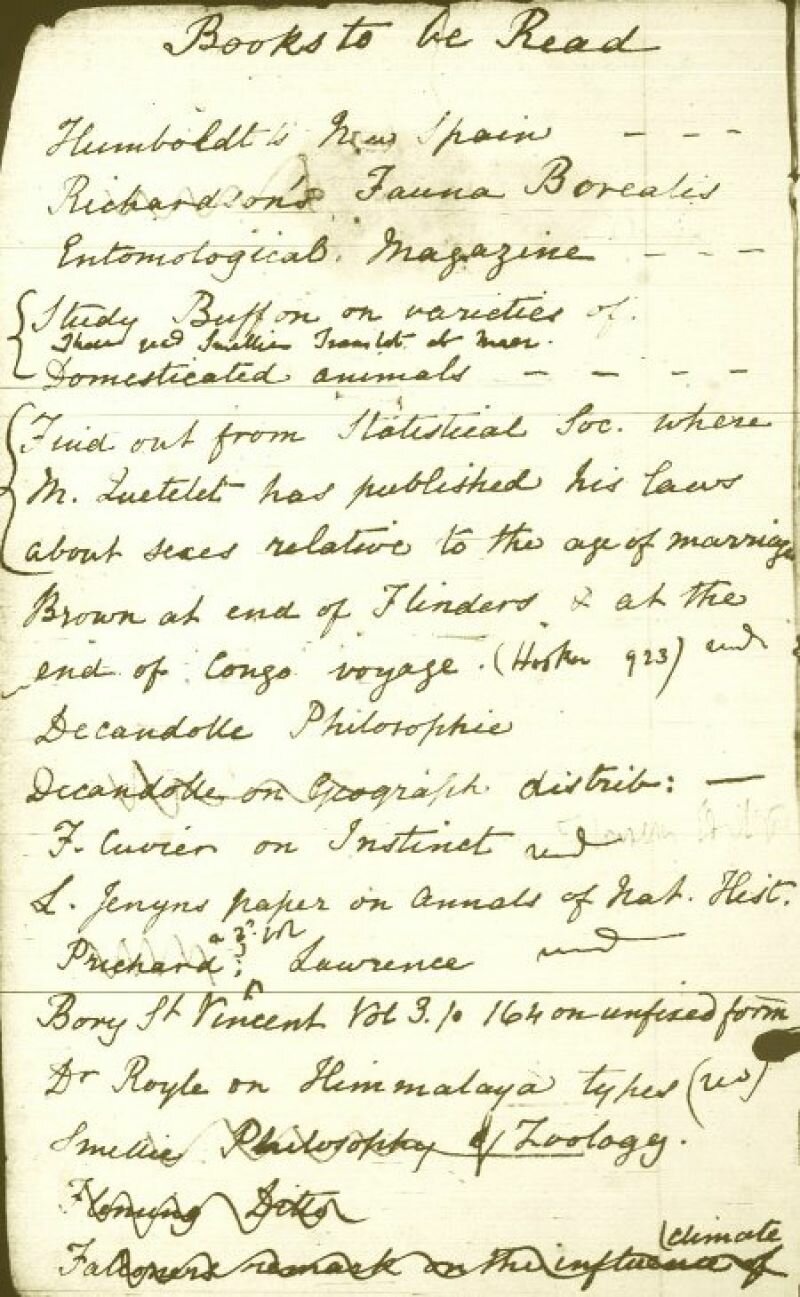

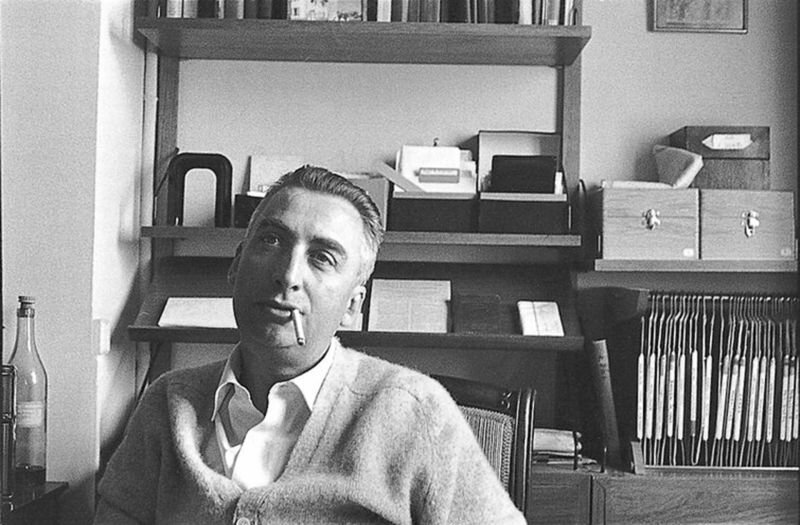

When an individual has shown extraordinary qualities or talents, the contents of a list they have made might become valuable to others. The lives of great scientists, musicians, actors, writers or designers are retraced and dissected by making their diaries or notebooks public. Whilst the content of their home is on show so is the content of their minds. Private information, messily scrawled across the page with changes and errors, supposedly give insight into a frame of mind. A laundry list suddenly reveals secrets of their lifestyle, an unseen side to their character.

This information, analysis, format, or story is irrelevant to the author; the content is what is of interest to them. Their document is plagued with encryptions of coding, different methods of ‘crossing off’, ticks, strike-throughs and circles around ticks. Only some entries have numbers, where clearly an attempt at prioritising has been made. Some have dates next to them, for deadlines and finales, giving an added importance, a ticking reminder. These juxtapositions need not make sense to others.

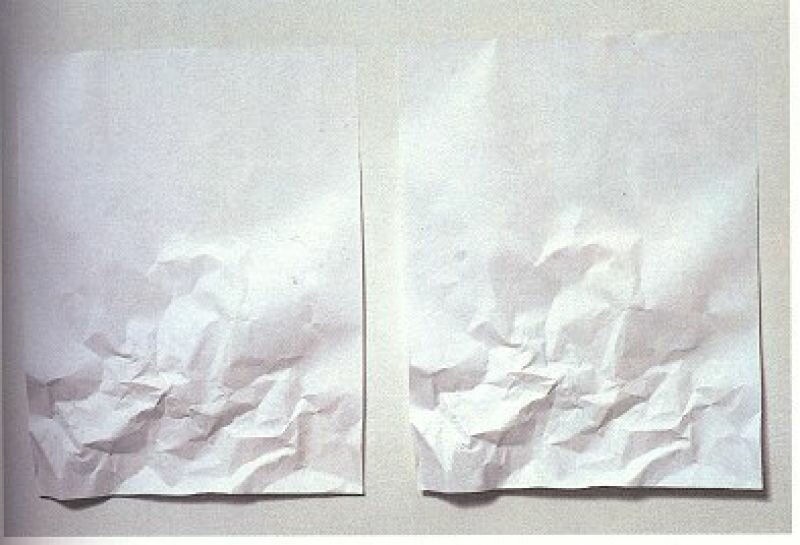

Having been created, a list triumphantly sits at the top of important papers. It is versatile and can be used as a bookmark, a coaster or a space to sketch; it is embellished with important things, mustn’t forgets and mental notes. It ages well. Every mark on this creation is part of its existence. Folds in the page create creases across the unused printed lines; they battle with the thoughts sprawled across them. A new dimension is added to the form where the author has rolled the corners back and forth between their fingers.

At the height of its usability, the list holds authority over its creator; unchecked items glare at you and make you feel guilty for the things you have not yet accomplished. A mutual resistance grows and other lists arise. Before the list has peaked it finds itself at the bottom of a bag, on a supermarket floor, wedged in a shopping basket, slotted in the corner of a sofa stuck to some crumbs, at the end of a book that was being read, in the shredder, at the back of another list, propping up a table, underneath a doodle, fallen on the pavement or sitting helplessly in the recycling bin, sitting next to the envelope that wasn’t chosen and another list that has efficient strikes through most entries.

On the off chance that a list may be revisited or found again by its creator, they might experience the sense of satisfaction that comes with being able to cross off multiple items from the list. The single action of drawing a line, or the flicking of a tick enhances the achievement of completion.