Hanae Wilke (1985, NL) is an artist and writer living and working in The Hague and London.

1000 Things is a subjective encyclopedia of inspirational ideas, things, people, and events.

Read the most recent articles, or mail the to contribute.

Hanae Wilke (1985, NL) is an artist and writer living and working in The Hague and London.

The immense hangar, an old converted bread factory, is lined with market stalls where families sell their old wares: junk that, pulled from the bottom of cellars and the dark corners of garages and cupboards, momentarily regains value, however slight. Hands grope through second hand clothing, mostly chain bought and cheap, grouped in slightly musty smelling endless piles.

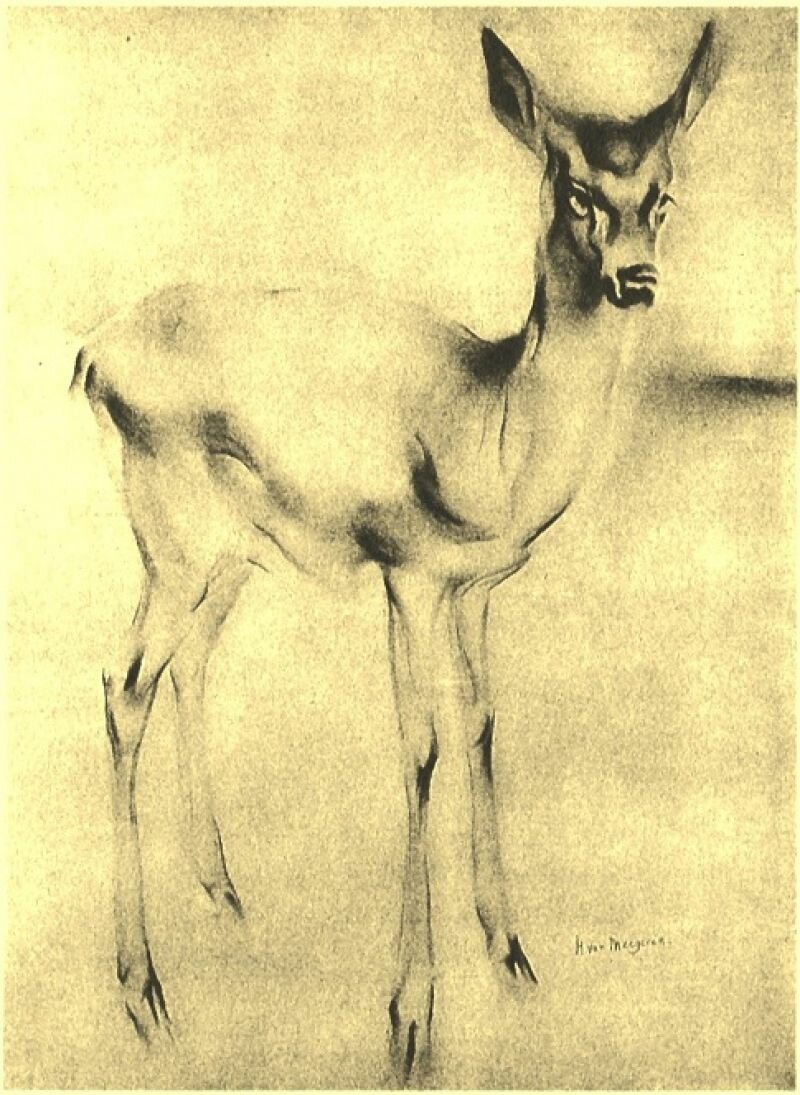

At the far end of a table covered in yellowing art books, old editions of classics frayed at the edges, and stacks of thriller pulp, sits a large folder. It opens to a collection of drawings, watercolours and sketches that are mostly abstract and frantically scrawled. I look up and catch the gaze of a tall, melancholy man with long mousy brown hair and silver rimmed circular spectacles. With a nervous excitement, the seller explains that these are the remains of his artist days that he sells alongside the used books. I buy an odd, demonic depiction of a creature drawn with Indian ink over a printed pencil drawing.

One late night sitting around my dinner table, a friend notices the ink drawing on the wall, and after taking a closer look, asks if it’s a genuine Han van Meegeren, the great master forger. As it turns out, the backdrop to the demon creature is a copy of Han van Meegeren’s most prolific pieces, namely ‘Hertje’ (or ‘Little Deer’), reproductions of which hung on the walls of thousands of Dutch homes in the 1920’s. But van Meegeren’s style was caught in the past and completely irrelevant in a world of Cubism, Dadaism, and Surrealism, and he was derided by the art world for his lack of originality.

At the start of the 20th century, detecting a forged painting was a fairly simple process: a swab of alcohol was wiped over the dubious canvas, a needle carefully inserted and checked for any oily residue. This would be the mark of a forgery, as an age-old canvas would be thoroughly hardened and deliver a clean needle.

Han van Meegeren bought cheap 17th century paintings to scrape off the original painting. Instead of oil, he used an early form of plastic named Bakelite to mix his pigments into paint. He would then bake his freshly painted antique canvas until the plastic fully hardened, and finished the simulated aging process by rolling the canvas and cracking its surface. Voila, instant Dutch Master!

Relatively few paintings by Johannes Vermeer have survived the ages. When in the 1930s a series of paintings began emerging from his supposed unknown religious period, they were eagerly snapped up by collectors, including the Rotterdam museum Boijmans van Beuningen, who paid what would today be more than 4,5 million Euros for Vermeer’s Supper at Emmaus. The painting, revered by art critics as Vermeer's masterpiece, was nothing more than a carefully executed van Meegeren.

Having foiled the art world that rejected him, van Meegeren lived a wealthy and lavish life all through the Second World War. But his life of decadence was disrupted when, after the end of the war, a Vermeer was found in Nazi henchman Herman Göring’s largely misappropriated art collection, and was traced back to van Meegeren, who refused to name his source. The outrage was immense: how dare he allow Dutch national treasure to fall in the hands of a Nazi? He was arrested for treason, a felony that at the time was punishable by death.

His plea to innocence was simple. He couldn’t possibly be a traitor, because the painting he had sold to Göring was not a Vermeer, but a forgery by his own hand. A sensational trial was carried out in a courtroom hung full of van Meegeren’s fakes. The art world was stupefied – how could they have been so utterly mistaken – and he was deemed to be a liar.

As a free man, Van Meegeren passed away from a heart attack before he could begin his prison sentence, and after his death, his paintings became so desired that van Meegeren forgeries began to flood the market.

My own Hertje still hangs on my wall, covered by the market man’s inky black drawing. Is he still no longer an artist? A failed artist can become a most tragic creature, overcome by vanity, envy, and consumed by bitterness. But Han van Meegeren’s exclusion from the art world led him to what is probably the most extensive art scam ever. “But sir, I'm sure about one thing: if I die in jail they will just forget all about it. My paintings will become original Vermeers once more. I produced them not for money but for art's sake.”

Tropes: a significant or recurrent theme; a motif.

The moment is inevitable. You’re in your studio, you’re working on a piece and a certain uneasy feeling creeps over you: you’ve seen this before. Or otherwise, you’ve felt happily contented with a completed work, satiated in state of smug recline... until you scroll through that blog or walk into that exhibition space and come across another artist’s work that undermines any sense of originality you ever hoped to have.

But fear not! You are not alone.

Perhaps we should be grateful for our ability to tap into the ‘cloud’ and make amends with fears of falling into the derivative. After all, one could argue that art making is essentially a social act (what is the artwork without the other?) so we might feel comforted by our inclusion into a world of like-minded colleagues, rather than feel the paralysing fear of appropriating one of the many art world tropes.

See, you might almost find it's unavoidable:

1. Plants

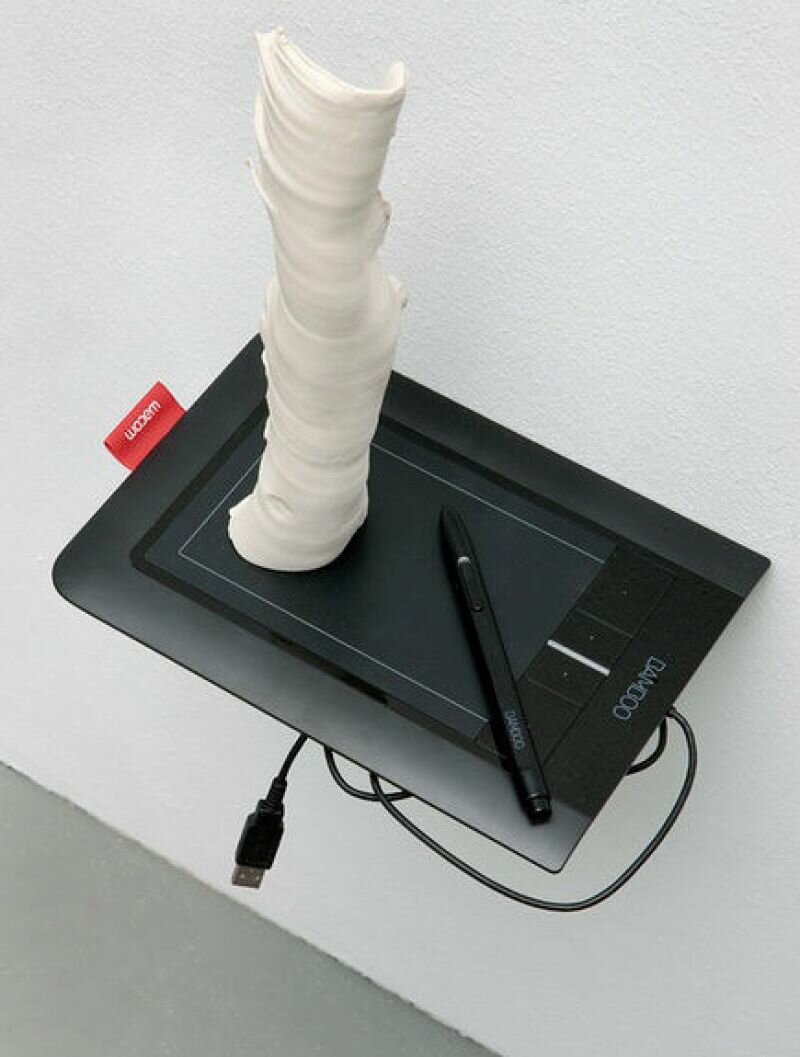

2. Digital Material Goods

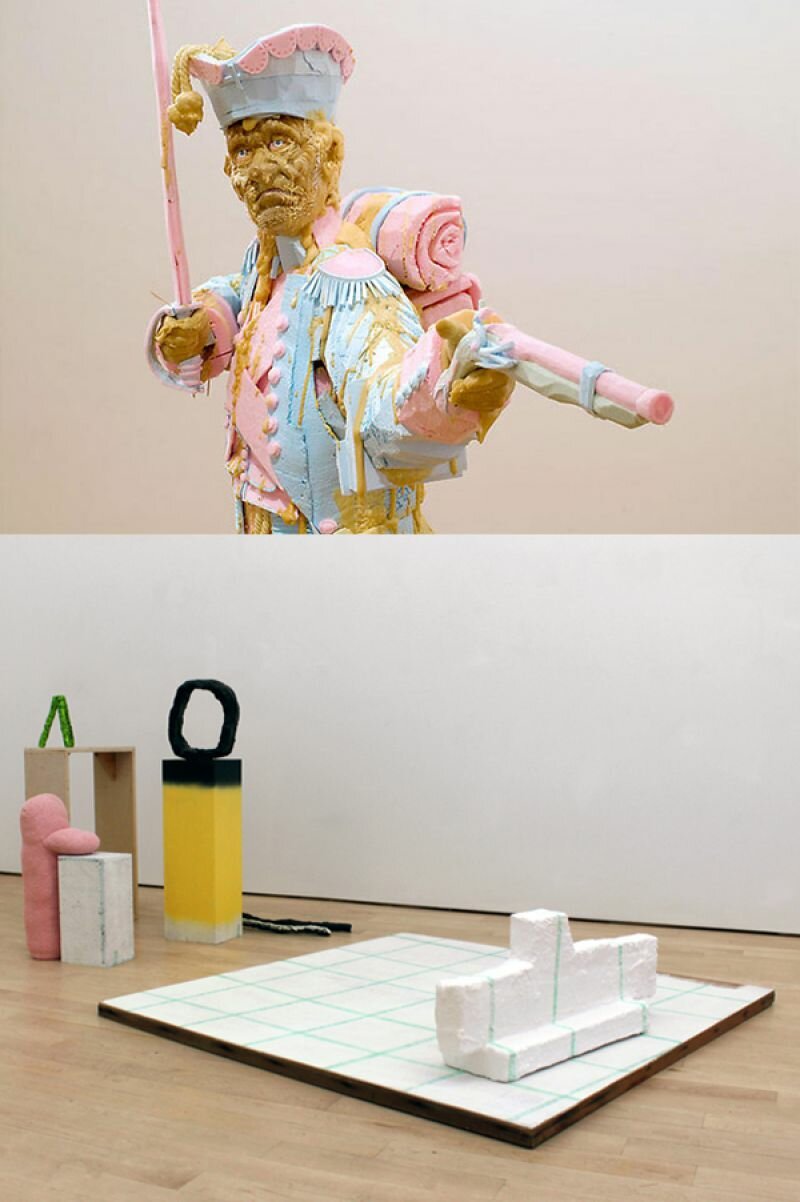

3. Foam

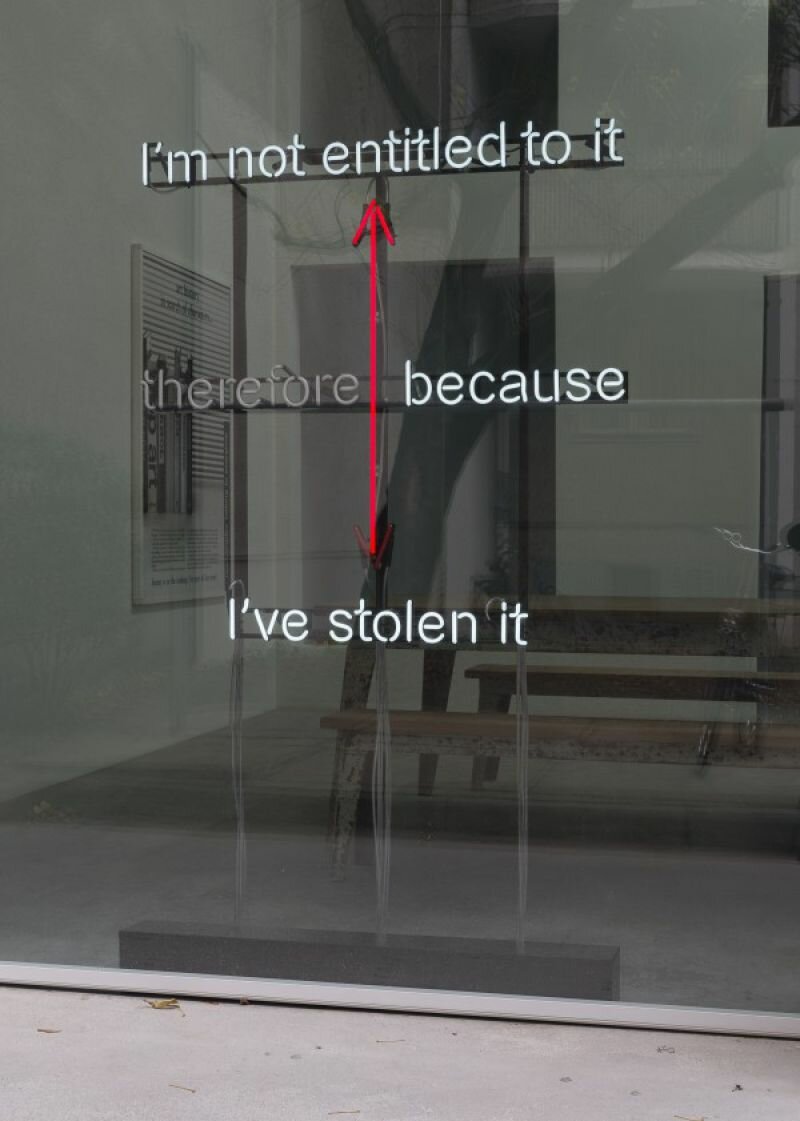

4. The Neons

5. Forever Gradients

6. Cool Steel

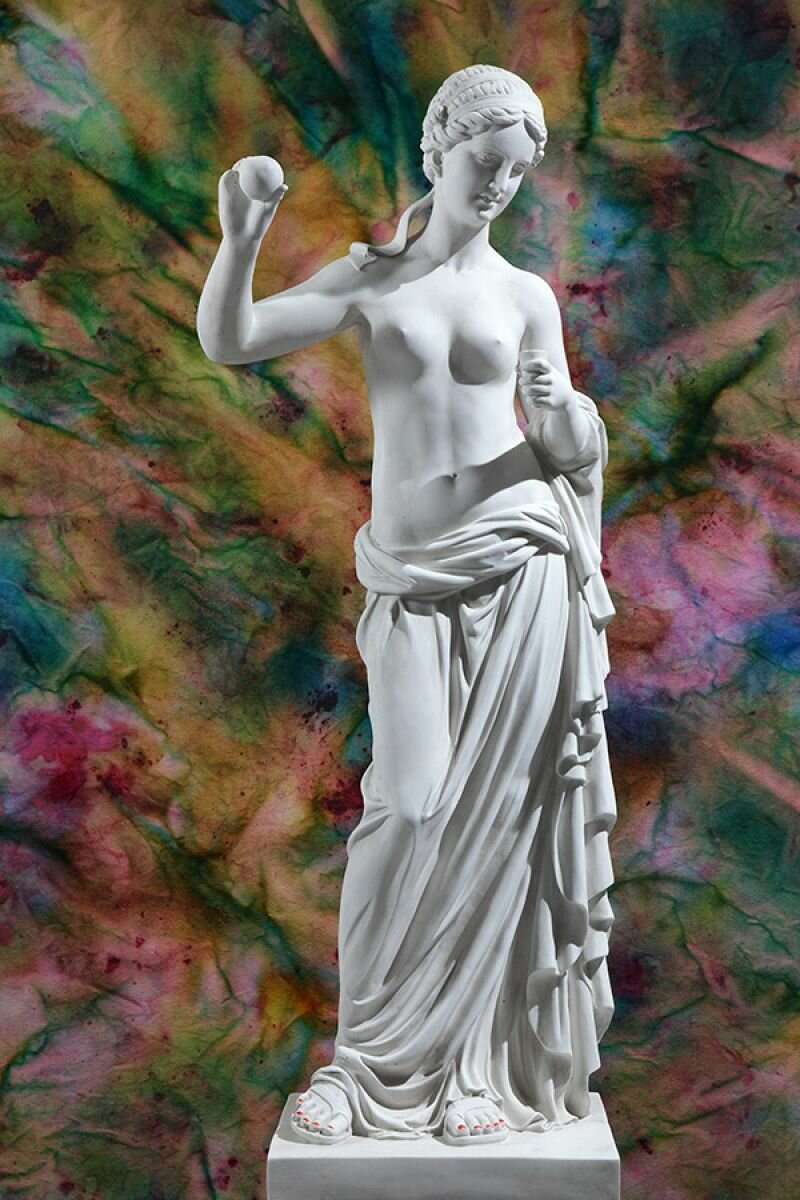

8. The Revival of the Classics

9. Marble Mania

10. Home Decor

Once upon a time, in 1913, Kandinsky predicted an art of pure consciousness, where we would find ourselves dematerialised and, in a state of telepathy, exhibit our artworks spirit to spirit. We might not be there yet, but it seems our spirits often end up sourcing from the same fountain.

There you have it. Now don't worry, go out, make stuff.

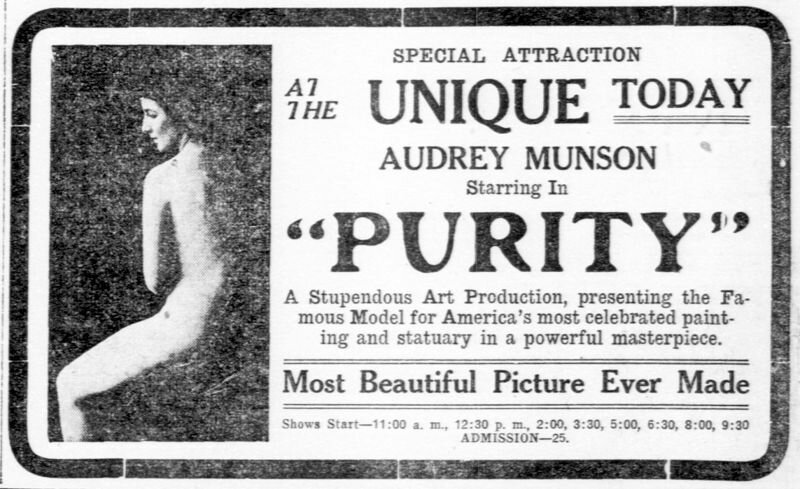

"The most perfect, most versatile, most famous of American models, whose face and figure have inspired thousands of modern masterpieces of sculpture and painting."

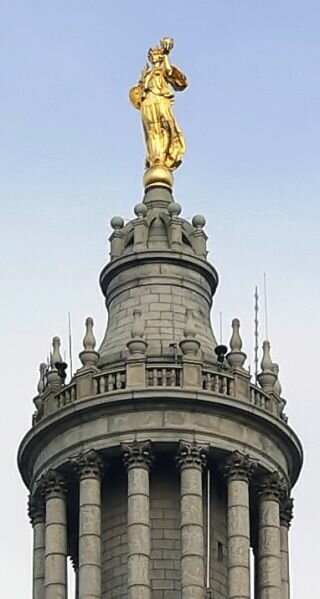

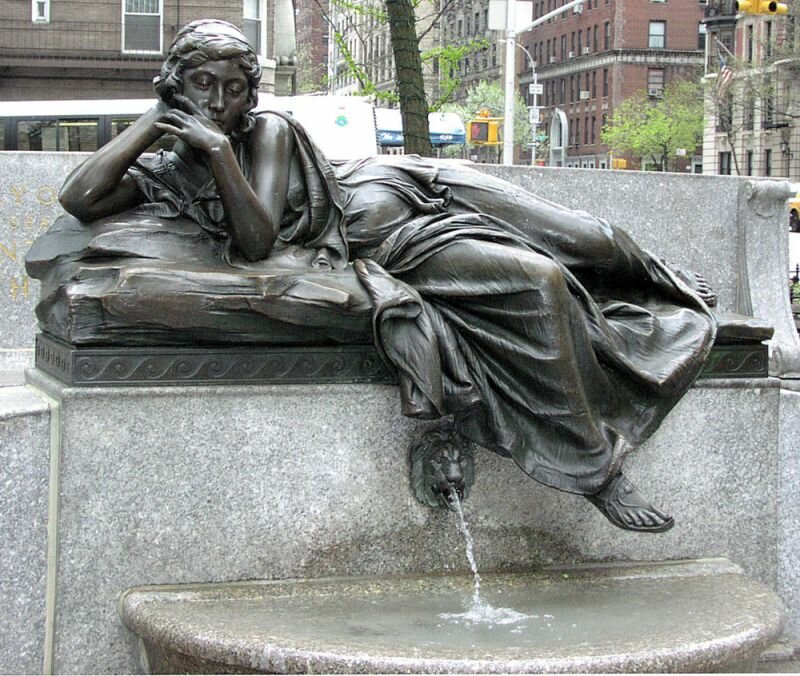

At the turn of the 19th century, the socialite Audrey Munson, known also as Miss Manhattan, was the muse of many and the most sought after model of all New York, becoming a ubiquitous figure on canvas, tapestries and stone. Still, her likeness graces many corners of Manhattan: from the Pulitzer fountain to the Civic Fame statue atop the Manhattan Municipal building, the city's largest sculpted figure after the Statue of Liberty.

Her fame and popularity had grown so vast that during the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exhibition, it was her image that was cast onto nearly every work shown.

In 1915, Audrey moved to New York to California to extend her career into the brand new film industry and boarded at the house of a doctor. His wife sent Audrey away when she began to suspect that the doctor had fallen in love with her. When his wife was found murdered not long later, the doctor was convicted of murder in the first degree. He hung himself before they could take him to the electric chair.

After the scandal, her reputation was destroyed and her career fell flat prompting the downwards spiral into which she would descend. She blamed “powerful forces” for the disintegration of her career, and fabricated an engagement to a certain Joseph J. Stevenson. When, according to her, the non-existent Stevenson broke off their betrothal, she ingested a solution of mercury to try and end her life.

Although she recovered from her suicide attempt, her mental health would continue to deteriorate and she was placed in a mental ward at 39. Here, she would reside for the next sixty-five years, and pass away in 1996 at the age of 105.

Helene Kröller-Müller, born into a prosperous industrialist family and Anton Kröller, a shipping and mining tycoon, were one of the wealthiest couples of their era in The Netherlands. Not only was Helene Kröller-Müller one of the first European women to amass a major art collection, she was also one of the first to recognise Vincent van Gogh’s talent, ultimately purchasing 90 of his paintings. Spearheaded by Helene Kröller-Müller, the couple set out to build a hunting lodge, the Jachthuis Sint-Hubertus— an enormous villa jutting out from the centre of the vast Dutch national park, the Veluwe.

Mrs. Kröller-Müller herself, as depicted in her study room.

Between 1914 and 1920, the build of the Jachthuis became one of Helene’s main attentions. She recruited the immensely successful architect now considered one of the fathers of Dutch modern architecture, H.P. Berlage, in an exclusive contract that bound him to the Jachthuis as his sole project. It proved an unparalleled endeavour for Berlage and he was set to design both building and interior, furnishings included, to the utmost detail.

Berlage’s motto, ‘unity in diversity’, was materialised through the Jachthuis: floors, ceilings, and walls were covered in triple glazed brick in red, yellow, blue, white, crème, green, and black. True to Berlage, many of the steel I-beams were left bare, although swathed in colour. The Jachthuis, its floor plan shaped like the antlers of a deer, exemplified a world of modern splendour.

The lodge was spared no luxury, and many of its features were a rarity in its days: electricity, a central heating system, warm water (although not in the servants’ quarters), and even a central vacuum system were installed. The tower overlooking the forests and heaths was fitted with an especially spectacular feature, the country’s first elevator. Once again, the servants were exempted from such luxury, and instead, climbed the many stairs to serve their patrons their tea.

The I-beams, visible and painted red.

Helene, being accustomed to a world of affluence, was not familiar with being denied her wishes. Inevitably, the design and build of the Jachthuis became a perpetual tug of war between Helene and Berlage. Once the foundations had been dug, she changed her mind and demanded to start over in a more favourable location on the plot. Although Berlage was presented with the extraordinary opportunity of a seemingly endless source of funds to create what was, in essence, a great gesamtkunstwerk, the strain of Helene’s fickle nature proved too much, and he walked away before the build was complete.

From each lamp, to each door made from rich, dark tropical hardwood nowadays too precious to consider, to every chair (those in the ladies room lowered to fit Helene’s petite frame) to the clocks, and even to the cigar humidifying cabinet—all were built in the vision of Berlage. Many of these objects in the Jachthuis attest to Berlage’s meticulous design, from the bronze sculptures bolted in place never to be relocated, to the legs of the furniture that fit perfectly over the square geometric floor tiles.

The legs of the cabinet fit perfectly over the tiles.

But nothing is as indicative as what one finds when lifting a corner of the dining room carpet. There, on top of the deep jade coloured glass floor tiles lies a thick red rug underneath which nothing but bare concrete is exposed. A bid to reduce costs? No, money was never an issue. The decision to keep the naked concrete, its banality dully contrasting with the luxury of its surroundings, was of a purely functional nature, a small gesture to ensure that everything stayed precisely as it should be, never straying from what Berlage envisioned. After all, you can’t quite move the rug if that’s where the tiles stop.

Lift the rug to reveal the concrete!

This morning, Marina Abramović stands at the entrance to the Serpentine Gallery to welcome the first visitors of the day to her performance piece, 512 hours. ‘Most artists do not say good morning but I do! Good morning!’ she says, and looks deeply into our eyes as we each enter. Once inside, we’re asked to leave our phones and belongings in lockers before stepping into the exhibition.

I’m handed a black strip of cloth to tie over my eyes and coaxed into the white room filled with more than a dozen other blindfolded visitors slowly shuffling around, many with their hands tracing along the side of the walls to keep themselves in check. Muffled noises reverberate through the large gallery space where the bodies of the others are the only obstacles for sound to bounce off of. Robbed of my vision, I am reminded of diving to the bottom of the ocean where the blue extends into an infinity that is endless as well as stifling and claustrophobic.

The invigilator who blindfolded me gently spins me around and I, disorientated, rely on my hearing in a bid to understand my position but can make little of the dull acoustic. My hands, too, find a wall and follow the contours of the room. Every so often I brush against another body and we both erupt in muted giggles. The touch of warmth, the physicality of life and energy within the other is a striking contrast to the cool of the wall. As I move through the space I find myself looking forward to these physical encounters, these intimate meetings that, devoid of eye contact, are based on senses that I’m usually far less aware of.

Suddenly, a soft hand reaches out to mine—it’s been a while since I’ve held a hand and this unexpected contact spreads like the warmth of an enveloping embrace. A calm, hushed voice begins to speak: ‘Walk very slowly, in slow motion. Pay attention to each of your movements’. His soothing voice echoes a semblance of love. Silently, we walk together, hand in hand.

This stranger’s words stirs a feeling deeply nestled within: I am taken care of while I am in a state of near helplessness. For an instant I am in love, that home-coming type of love, perhaps the greatest kind of love! Minutes later, he releases my hand: ‘Carry on without me’. And I continue, gliding through a sightless world and floating on the remnants of the briefest infatuation I’ve ever known.

Rolf Nowotny, Deaf Parent, 2013

Relieved of my blindfold, I walk into the next room where a kind faced girl, another invigilator, leads me to a space where row upon row of cots are laid out. Most of the cots are occupied by visitors wearing ear defenders. They seem to be asleep. She gestures to an empty bed and I lie down. She pulls a thin purple cotton sheet over me and her face floats above me as I close my eyes. Once again, I am pulled into a worriless childlike world, where the maternal figure moves me to a long forgotten state of surrender. Like the shepherd was my lover during my minutes of blindness, the girl momentarily becomes mother.

After my session, I visit the toilet. The girl whose face lingered in the darkness of my closed eyes exits a stall as I await my turn. When our eyes meet, I smile at her and she returns the gesture, although the tenderness of our previous exchange has disappeared. Strangers once again, indeed, and the gallery, too, has reverted to just that: the white cube.

And I realise that I have just fallen for the Marina method despite numberless reasons to be wary: Marina’s embrac of celebrity status and that odd goddess-like persona she strives towards, how my ‘authentic’ experience is induced by paid invigilators repeating the same gestures daily, and how the performance is basically a series of new age mindfulness exercise. And yet, despite this awareness, I’ve gladly given in.