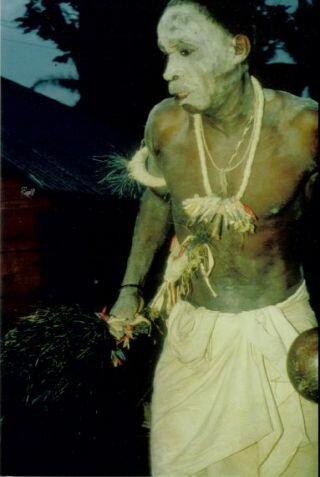

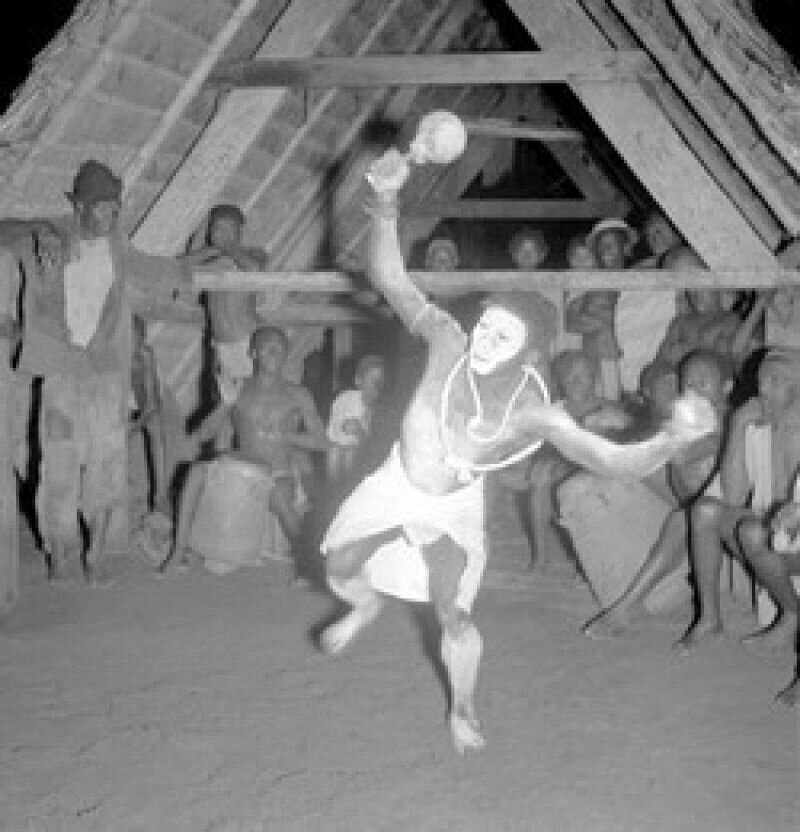

A lecture at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague on good and evil closed with a ritual performed by Winti priestess Nana (Marian Markelo). A few weeks later, I went to meet her to find out more about Winti.

What is Winti exactly?

It's a way of life that deals with the balance between yourself, nature and the people around you, your ancestors and your spiritual mentors. You can turn to Winti for support at any given point in your life.

Is it a religion?

Not when you compare it to Western religions: there is no leader, there are no writings, and it’s not institutionalised. If you consider religion to be about connecting, you could call Winti a religion. The word religion has many meanings.

Where do you find Winti?

Winti originated in Suriname, and it’s comparable to Santeria in Cuba and Candomblé in Brazil.It deals with nature, living people and the people on the other side of life (in Winti they are with us). Nature is the main focus, it's about everything that is a part of nature but also about the people that no longer posses their physical bodies.

The western world is completely reliant on rationality, on facts measurable through clear cause and effect. Scientists have led us to believe that things exist only when they can be measured. Because of this way of thinking, we have lost sight of so much. People have grown estranged from nature and from who they truly are. They focus on everything around them, but not on themselves and nature.

Winti is a model for harmony, it ends contradictions: people who are here have to communicate with people on the other side.

What does nature mean in Winti?

The Winti see humans as advanced beings of nature and if we start with ourselves we'll be able to set the right examples for others. When I perform my rituals I make sure the waste material is dealt with properly, in the garbage or in the forest. It starts with the little things: like not dumping your rubbish just anywhere, not spitting on the earth, keeping yourself and your property clean. Otherwise the gods will be reluctant to approach you, they wouldn't visit a dirty place.

People are too involved with the superficial, think that nature is theirs, and that they posses the material world.

How did Winti come to originate in Suriname?

Winti is truly Surinamese. It finds its origin in the time of slavery. In Suriname different groups of people were mixed and Suriname succeeded in creating a whole out of all those African elements: Winti. Until 1979 the practice was prohibited by the Dutch, which meant that many elements of Winti were lost.

What made you get involved with winti?

I wasn't raised with Winti, my mother was a member of the church and my grandfather was even a preacher during the time of slavery. Winti has always been with me: when I was thirteen years old I had to clean the chicken shed, I sat down there quietly. I heard a voice inside me say: 'you already know everything you need to know, you're still a little girl, but we're going to make sure you'll know everything. The supernatural is inside you.'

I went inside and told my mother: 'I won't be going to church anymore.' My mother and father supported their children to do what they wanted to do and to focus on the things they were good at. They accepted our individuality.

One day, my mother sent me to the market to buy fish. I wore nice American clothes that I had picked myself. Yes, I like to show off a little. A man paid me a compliment, 'O little girl, you look so beautiful.' 'It's none of your business,' I answered. I didn't accept his compliment. He kept on repeating his words. It bothered me. I had a nice bike with a little bag on the front, I collected stones thinking if the man would bother me again I'd throw those stones at him.

But right when I wanted to throw a stone at him, the man suddenly stood at the other side of the river. This was not good! I biked home as fast as I could and when I arrived my mother told me I was rude and impolite: you shouldn't throw stones at old men, you should say thank you when someone gives you a compliment.

Later in life, I decided to move to the interior of Suriname to work as a nurse. Three days before I let I was asleep and had the following experience - it was not a dream, but an observation. In my sleep a man approached me, he was made out of bronze, he looked beautiful. He told me: you're going to Stoeli [an island deep within Suriname] and I will introduce you to all the people you need to meet.

People were waiting for us all around the shore and the man would say: this is the one, this is her! In a big wide-open field men and women were circled around an iron pot, cooking. The man said: I'm going to put my hand inside and you should do the same. I put my hand inside the pot. That man took hold of me, I looked at him, at his smile, and saw he was the man from the forest.

That dream put me in a trance and I screamed so loud that the neighbour came and forced the door. She recognised that what was going on was Winti. When I came to, she had arranged all kinds of things around me: pimba (white clay), gin, a squash. She told me: ‘Girl, you need to do something, you have Winti, you have to tell your mother.’

Who is this man?

This Winti is a god of war, he very manly. It means that I'm not afraid of anything. As a kid these qualities made me rude and strong-minded. You see, you can’t ever really choose your way, it was always in me and in my destiny. You receive skills and insights to be able to do what you are supposed to do, to reach your destination and on the way, the Wintis will find you. That's how you reach faith, or your destination, with help of the Wintis, the Jorkas, and the spirits of your ancestors.

My guide is a Kromanti Winti and I love him—he’s a beautiful sculptured bronze man, and he’s strong. Although I am a woman, his power gives me a masculine strength.

But a god of war sounds frightening to me, does he contribute to the good in the world?

This Winti is a Kromanti, a god of war, a thunder god with knowledge of herbs and rituals. Although this might sound negative, one must keep in mind that during slavery the power of the Kromanti was necessary—they were fearless and heroic spirits. Where battle is necessary they come, they take action and they clear up the mess.

When I'm in need, he will take over. In Amsterdam, I was attacked by two men and the Winti took over. I call him god of war because of those qualities. It's a force that was given to me by my enslaved grandparents.

And through the Kromanti you became a Winti priestess, how did that happen?

We performed rituals in the outback of Suriname to properly initiate me and give me tools. I know what to do with them. As an initiation you marry your Winti, I receive energy from within, also to help others.

How do you see, from the perspective of Winti, the role of the artist?

In the west, spirituality is on the sidelines. The emphasis on the material has not only brought prosperity, but also an imbalance between it and the immaterial, which is vital to society. Where we stand today, the artists’ role is to revive the immaterial and spiritual to bring society back to balance