Before Richard Klein, professor of French in New York could quit smoking, he first needed to investigate the reasons for his addiction. In his book, Cigarettes are Sublime, he writes about the cigarette as a glorious acceleration towards death and finds support for his argument through film and literature.

The most beautiful encasing of tobacco is the handwritten letter.

At the start of the last century, French author Theophile Gautier travelled to a far corner of Spain where, not only were cigarettes packaged in a wild array of colours, he found that the cigarettes themselves were made from a multitude of coloured paper. The paper, dyed by the liquorice flavouring, must have been cut from highly personal letters. As Gautier examined each separate cigarette, he realised he was looking at fragments of declarations of love, business quarrels, confessions, pleas-- the tobacco was rolled in life itself.

The reader then sets fire to the story. He watches the cut up histories curl, crinkle and disappear and with that primitive cigarette, thinks of Greek statues or the Boroboedor, or of other white and grey depictions that once were coloured brightly.

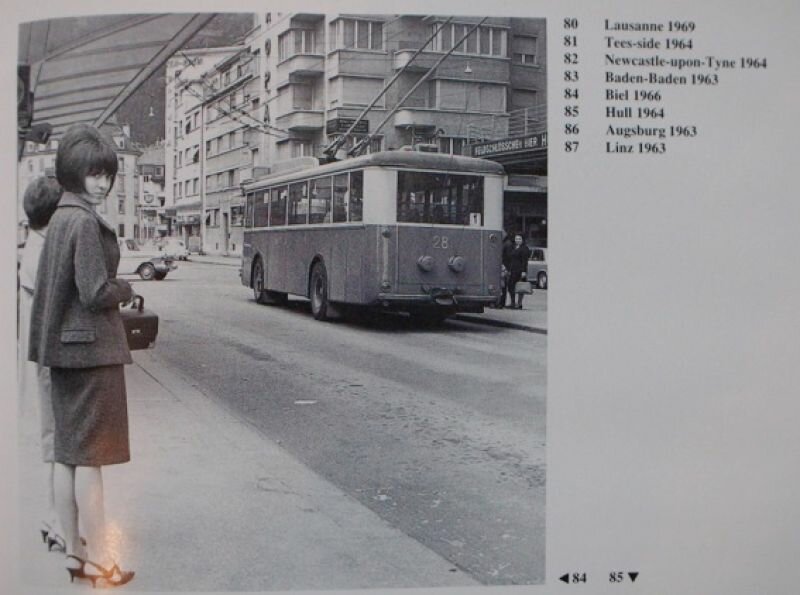

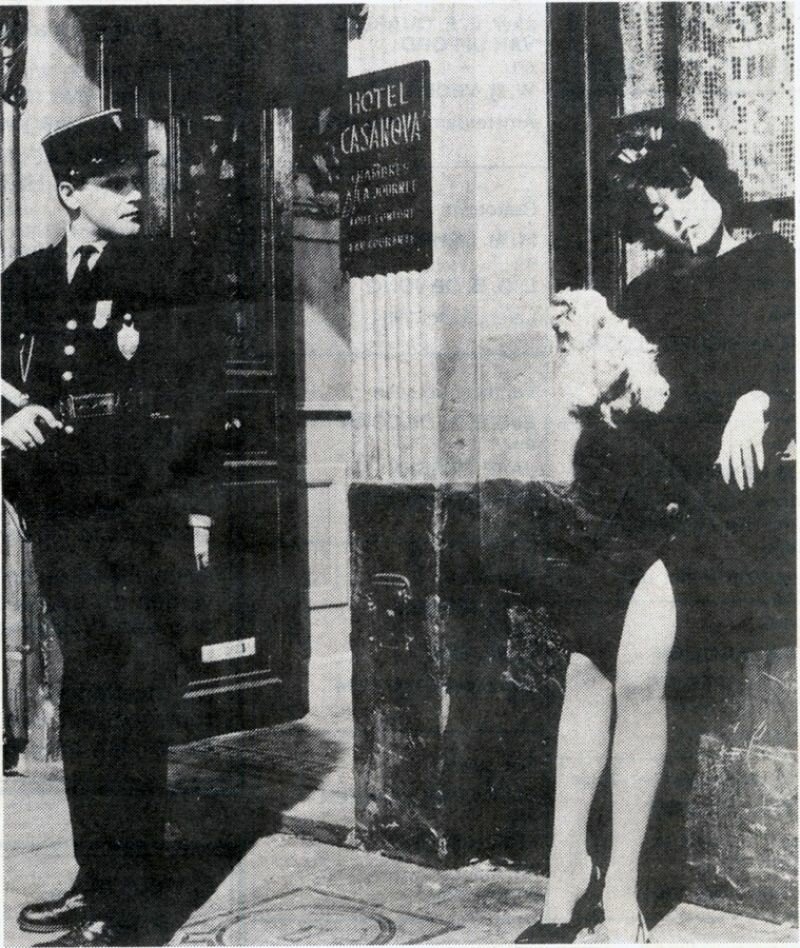

Thirty years after Gautier found the letter-wrapped tobacco in that far corner of Spain, Brassaï stands behind a Rolleiflex perched atop a tripod at the Rue St. Jacques in Paris. He gazes into the lens while we remain unknowing of his subject. Not far off, another camera stands before another photographer who catches him in this sombre state.

A cigarette hangs from his mouth, long, exceptionally fat and extremely white against the darkness. You wouldn't think it anything special, if Brassaï hadn't appointed a caption to the image that transforms the cigarette into the main character.

"A Gauloise is for a certain lighting, and a Boyard for when it's dark," he says, without revealing which of the two it was.

The darkness in the picture conjures the suspicion that it was most likely a Boyard. With its 10,5 mm diameter, it was slower to burn than the Gauloise, 8,7 millimeters white. For Brassaï, the cigarette was not only a stimulant, but he also used it to measure the time of exposure for certain recordings.

Four years before Brassaï smoked that cigarette, Erich Maria Remarque wrote that on the battlefield, cigarettes and cigars were handed out as the hour of battle was near. Sucking air into the lungs decreases the fear of dying. Nicotine enters the blood, the pulse raises, the pressure of the arteries increases. The smoker feels that every new cigarettes changes something in him. Despite revelling in the enjoyment of his smoke, he’ll remain somehow conscious of a danger he simultaneously denies, a menace he willingly allows to enter his body.

It’s exactly for this reason that smoking has a purpose during war. The soldier’s fear is amorphous, because the enemy is hidden. There is no precision to his fear. He lights a cigarette, and the area of threat around him is tempered to his hand, his lips, his mouth, his lungs. You could compare it to a man afraid of open spaces; he runs across a wide, long bridge and sticks a needle in the palm of his hand. By this action, his surroundings focalise to that one pinprick in his skin, and before he knows it, he’s on the other side.

The tobacco wrapped in words, the Boyard as a meter of time, and the rollies that shroud the threat of the enemy are just a few of Richard Klein’s examples in Cigarettes are Sublime. The book makes one think of different coloured paper, all rolled up into one big ball. However you approach it, no colour is favoured. It’s infused with stories, confessions, and reflections that attempt to remove the permanent air of doom inherent in the cigarette.

Klein’s book is a paradoxical praise to the cigarette. Upon finishing his book, the poet of nicotine quits, perhaps for good. Not because of any physical complaints, or because he agrees with the American Ministry of Health’s plans to prohibit smoking in as many public places as possible. Klein is wary of a nation that attaches labels of warning on cigarette packets, limits the advertising of tobacco, but at the same time subsidises tobacco farmers. In 1992, the USA’s tobacco export amassed to 3,7 billion dollars.

Richard Klein teaches French at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. His age is never mentioned, but he’s most likely just over fifty, “closer to the end of my career than to the start.”

Cigarettes are Sublime is his first, and probably his last book, which he wrote because he refused to simply quit smoking. He first wanted to understand the many reasons for his addiction before giving it up.

The eternal final cigarette held by Zeno’s Consciousness’s hero held until his death does little to dissuade Klein. While reading Italo Svevo’s analysis of the fallacy and self-deception of smoking, he became aware that smoking is not only harmful, but can also be seen as a moment of reflection, a choreography that seduces the fingers over and over again.

To Klein, Zeno became a dandy who preferred the daily struggles with smoking above society’s ridiculous issues. It was in his footsteps that this professor of philosophy decided to appoint the lead role in his book to the cigarette. Instead of choosing to write a novel or a story, he opted to write a reflection and tried to look for images that portray just how deeply the cigarette is anchored in existence.

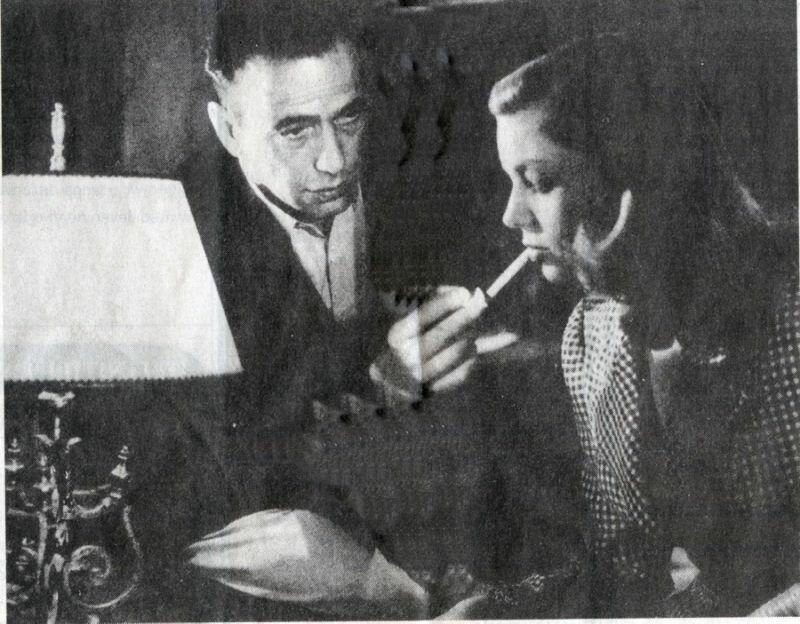

America might soon ban Michael Curtiz’s 1942 film Casablanca, the disguised anti-axis resistance film, because every character but Ingrid Bergman smokes. The movie’s hero, Victor Laszlo, played by Paul Henreid, half covers his face with his cigarettes as though, according to Klein, he has a secret to hide.

Although his own struggle with smoking is never explicitly mentioned, Klein’s dilemma is what grants his book its power. The continuing, the stopping, this one will be the last, oh, why should it, it could also be the second last, I could stop tomorrow, or next week, next year—the half-hidden repetitive doubt of one who wants to quit seeps through every image.

Cigarettes are Sublime is a drama in the form of a philosophical reflection: Carmen, Casablanca, l’ Être et le Néant; however precociously Klein dissects these works, their first purpose remains to illustrate his irresistible pleasure in smoking.

He quotes Theodore de Banville, who found the cigarette to be the most demanding of his mistresses. The cigarette allows for no other love, the passion is absolute, all-encompassing. Later on, Klein refers to smoking as the decrepit enchantment of risk, suspicion and shame.

It’s precisely that, according to Klein, that makes a cigarette so very seductive. After all, a mountainous landscape is most beautiful when viewed from the edge of a cliff. He suspects that the artists he uses to support his claims would never have created their best works if they had quit smoking. His arguments are completely romantic. Each drag of a cigarette is a glorious advancement towards death. Life is attributed its value by the risks that might shorten it. In his self-conflict he continuously reverts to the lyrical—describing how in Casablanca, a waiter brings out two glasses of champagne. A soldier inhales deeply, exhales, inhales and for a few moments, the entire screen is filled with an extraordinary cloud of the finest grey, floating above the crystal, the glasses themselves seem to smoke, catching all the light of the café.

Klein refers to this short occurrence as an epiphany, a moment of victory. From this moment, Cigarettes are Sublime takes off. Klein’s territory lies in those small gestures made for the sake of smoking that are otherwise left unexplored. A cigarette shaken out of a package, slid in between lips, the lighting of a match, inhaling and exhaling; moments that go unnoticed, negligible movements that precede an actual event.

Klein doesn’t see it that way. With every new cigarette it’s as though the luxuriously nonchalant smoker marks a moment in ever-expanding time. Call it a doubling of time, if you will. The work, or whatever it is that must be executed, continues while simultaneously in an intricate collaboration with tobacco, fire, smoke, hand, ash, lungs, mouth—a number of minutes lacking any sort of narrative are exalted and are untouchable.

Alfred Hitchcock’s light-hearted comedy, To Catch a Thief from 1955, isn’t named in the book. Still, there’s a scene that epitomizes Cigarettes are Sublime that in today’s world, where tobacco is met with great distrust, would never be shown.

Actresses Jessie Royce Landis and Grace Kelly play a wealthy mother and daughter who become embroiled in a tale of crime with the suave criminal Gary Grant. The two women are at breakfast in an overtly opulent hotel room.

Landis speaks. While her toast and omelette sit before her, she lights a filter cigarette and starts an excited monologue explaining the latest events. To bring her point across she gesticulates, waving her hands through the veil of smoke, or as Klein would say, through the image of thoughts.

As she finishes speaking, she points her cigarette downwards and sticks it firmly into the untouched yolk. It’s the punctuation after the last sentence. The fire douses with a hiss in the breaking yellow of the inner core.