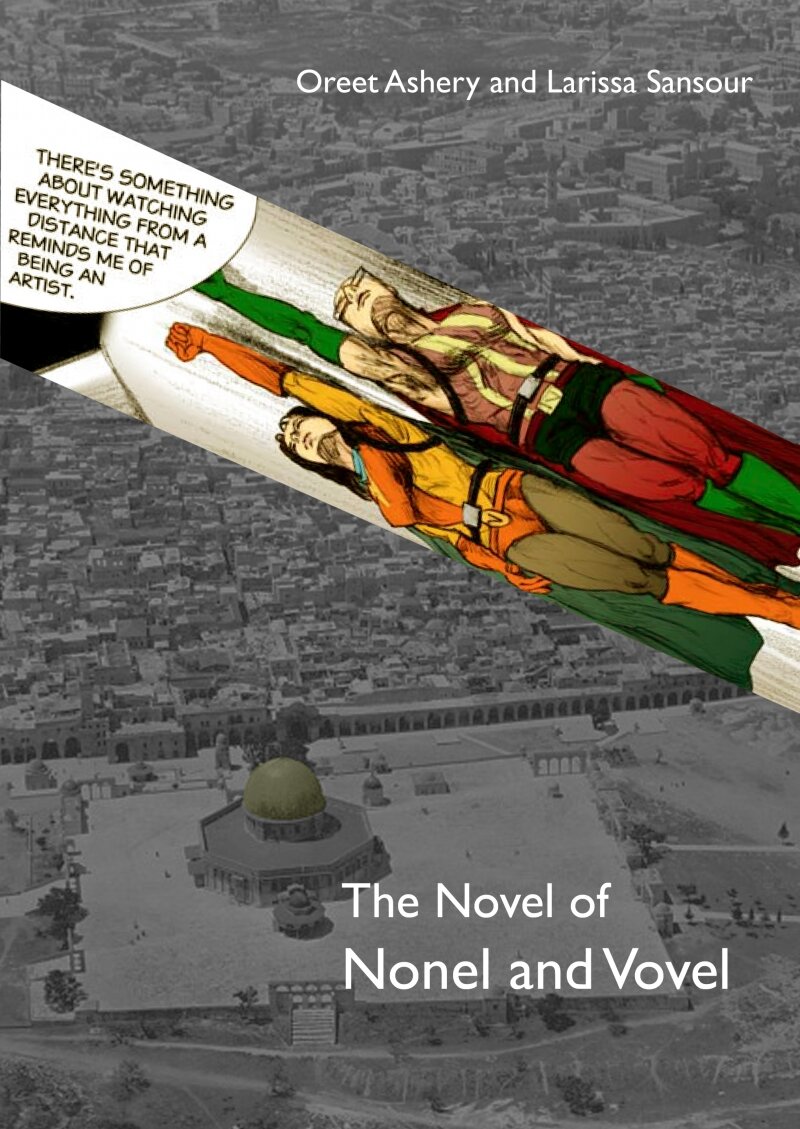

The Novel of Nonel and Vovel

© Oreet Ashery and Larissa Sansour

The art world is enamoured with many “-isms”: they sound distinguished, contemporary, intelligent, and articulate. But more than anything else an “-ism” is an idea-clustered temporal designation, right for a specific space-time coordinate. It has become a protective cloak for art workers to arm themselves with “-isms” when venturing out on a mission, as it supposedly demonstrates an understanding of a current moment, false or not.

There is one “-ism”, however, which seems oblivious to trends, hypes, and professional commodification, yet which is markedly contextual and genuine, and demands you to undo any protective clothing: heroism. Though its ring might sound unfashionable and outdated, yes even archaic, artistic practice and the heroic make for good bedfellows, yet recently this natural match has been prone to amnesia. Heroism, in this sense, is not at any time to be confused with ego, politically correct righteousness or misplaced didactic sentiments. For are we not grandly fed up and done with chatter about morals and values from a pedantic and paternalistic state, and societal pressures to perform in some way or other?

Do we really need post-modern tales of the epic, populated by modern-day art heroes who are larger than life? (no, please) Have we not regurgitated art movement after art movement, biennial after biennial, the next big theoretical turn after the other, and the – pick a number – next “radical” vision of the next star curator on the block? All that has nothing to do with heroism. So what is this notion that allows us to accrue a particular value from our precarious labour that is not measured monetary terms. Is there, in an era of capitalist consumption, room at all for an artistic heroic that refuses to comply with flavour-of-the-day expectations, and generates meaning out of necessity rather than out of market or policy demands. (yes, there is!)

Heroism is not to be found in tweaking the market till your fingers bleed, lest your concepts dry for a few crumbs of recognition and square metres of gallery space…or that coveted thank you note in an expensively produced catalogue. Heroism is modest, often undetectable, for it goes against the grain of our conditioned and framed vision. To have the courage to read, create, think, write and perform against the grain is what constitutes the life and blood of critical intellectual and creative practice. Somehow we seem to have lost this in the maze and haze of appropriating other “-isms”. So say it softly and say it sweetly: “there is no -ism in heroism”.