The extraordinary life of James Tiptree and Alice B. Sheldon (1915 – 1986.)

The author Julie Philips, residing in Amsterdam, won a prestigious American prize with her biography of sci-fi legend James Tiptree. His life story is hard to believe.

At the start of the seventies, the sci-fi world was mesmerised by a mysterious author. James Tiptree Jr. supposedly worked for the CIA and could therefore only communicate via an anonymous postal box. He had travelled sinister territories and knew how to use a weapon. His energetic, possessed stories of sex and death were extremely masculine while always remaining attentive to the ‘unseen’ woman. A feminist jock? A sensitive macho?

In Julie Philips’ National Book Critics Circle Award-winning book, James Tiptree Jr., the Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon, the mystery of Tiptree’s hidden life is unravelled. The Dutch-American biographer Philips reveals an unlikely history. Born a child to rich travellers in 1915, Sheldon travelled the darkest reaches of Africa as a young child. As a teenager, Alice ran away with a violent drunk whom she left after six years to join the newly formed female division of the army. She struggled with homosexual feelings, but all her greatest love turned out to be femme fatales, who all either went insane or died young. She became a photo analyst at the CIA, where she met her husband, Huntington (Ting) Sheldon. Together, they bought a chicken farm, upon which she decided to study psychology (bipolar career planning!) As a researcher, she was a failure. Falling into a depression, she swallowed every upper and downer she could lay her hands on. Never did she feel like she could be her true self. This idea had much to do with the dominating presence of her mother, who wrote travel stories and was a prominent member of Chicago’s high society.

From a young age, Sheldon read science fiction, a guilty pleasure for which she often felt she needed to be apologetic. However, since the war, her pulp sci-fi had undergone a great transformation. No longer were the stories about green men and scarcely clothed women undoing their bras, but they had becoming reflections on nuclear war and overpopulation. The ambitious young hounds of the New Wave added a literary sensibility to the genre. Science fiction would not only be a literature of ideas, but come to fruition both stylistically and psychologically.

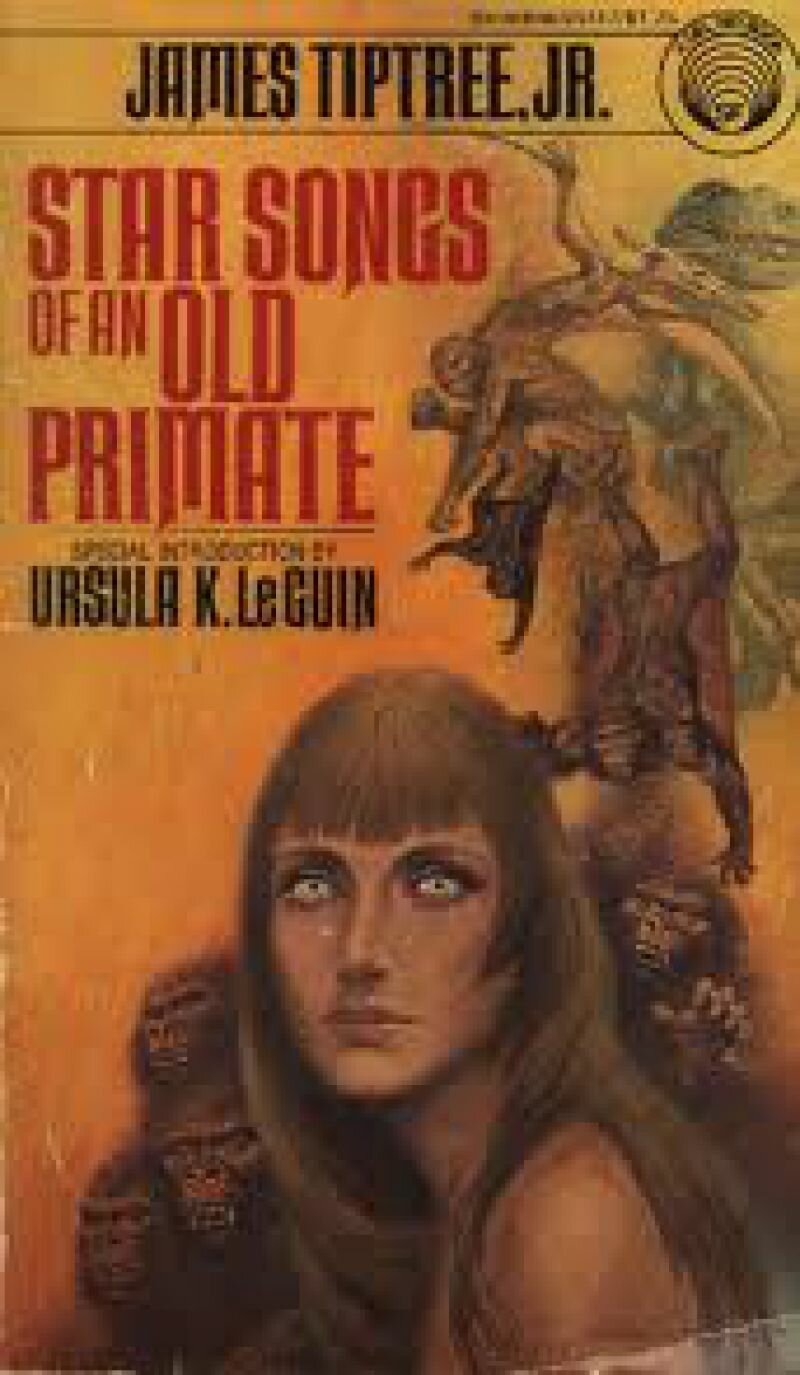

It’s this climate in 1967 in which Alice Sheldon began writing science fiction under the pseudonym James Tiptree. Leading editors like Frederik Pohl and Harry Harrison saw potential in her early work. Her stories would soon start becoming more personal and grim: the expression of frustrations that Alice could not ventilate in her every day life. The joke started becoming serious. Tiptree gave meaning to Sheldon’s meaningless existence.

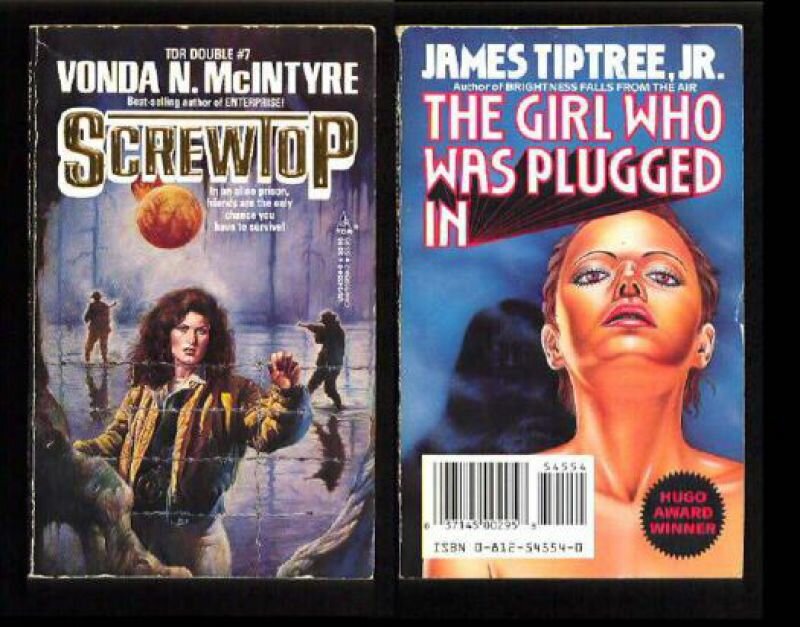

A number of Tiptree’s novels became classics. In “The Last Flight of Doctor Ain” (1969) the protagonist flies around the world to save his love – and this becomes gradually clarified: the Earth itself – from demise. To do so, he releases a deadly disease to eradicate the whole of mankind. “The Women Men Don’t See” (1972) is a satirical story in which federal agent Don crashes into the bush with two women. He constantly wondered about their motives, until they chose alien abduction over being “cared for” by him. And in the gripping “Love is the Plan, the Plan is Death” (1971) we follow the sexual awakening and the progressive dying of an insect. Under a second pseudonym, Raccoona Sheldon, she wrote “The Screwfly Solution” (1976,) in which alien abuse the aggression inherent in male urges, which results in the men annihilating all women in a frightening, all-natural way. Tiptree’s stories nearly always end in death and usually relate to sex in some way. Between man and woman, and between man and the “other.”

The very personal charge to Tiptree’s stories and columns would end up destroying him. It happened when Sheldon’s mother died in 1976. Someone compared a column by Tiptree describing his mother’s death next to the recent obituaries. A rumour started, claiming Tiptree was actually Alice Sheldon and lived in McLean, Virginia.

For Sheldon, the discovery was the beginning of a nightmare. She began to grow paranoid, and feared that her work was criticised more heavily because she was “just a woman.” In actuality, her work was becoming weaker because she “lost” the voice of Triptree. She saw herself as an empty shell, a failed human, a half-hearted version of the man she could be on paper. And she was growing old – unforgivably and unbearably old. This ended in a violent conclusion. On the 18th of May 1986, Sheldon first shot her husband before shooting herself. Seeing as suicide was constantly in her thoughts, she had chosen life for a long while. Now she chose death, so prominently present in her stories.