I’m on the road, heading for Georges Perec. The exhibition Regarde de tous tes yeux, regarde – l’art contemporain de Georges Perec brings together work by 68 artists that somehow correspond to the characteristics of Perec’s writing. After a ten-hour drive I arrive in Dole, France, where the exhibition is taking place. I enter a Chinese restaurant and order a 1664 Kronenbourg. Asian girls in summer dresses surround me. They laugh and stare at me. I take a snapshot. They don’t mind. Seem unmoved even. The fish in the three aquariums bounce back every time the camera flashes.

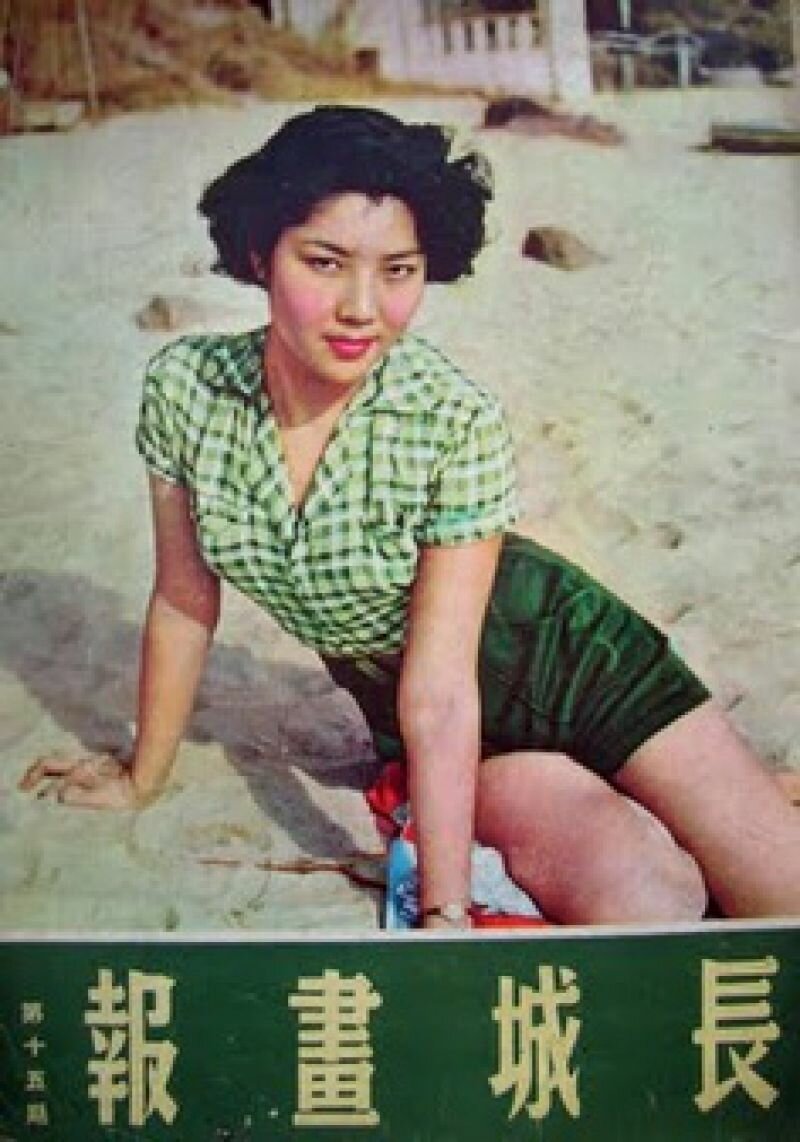

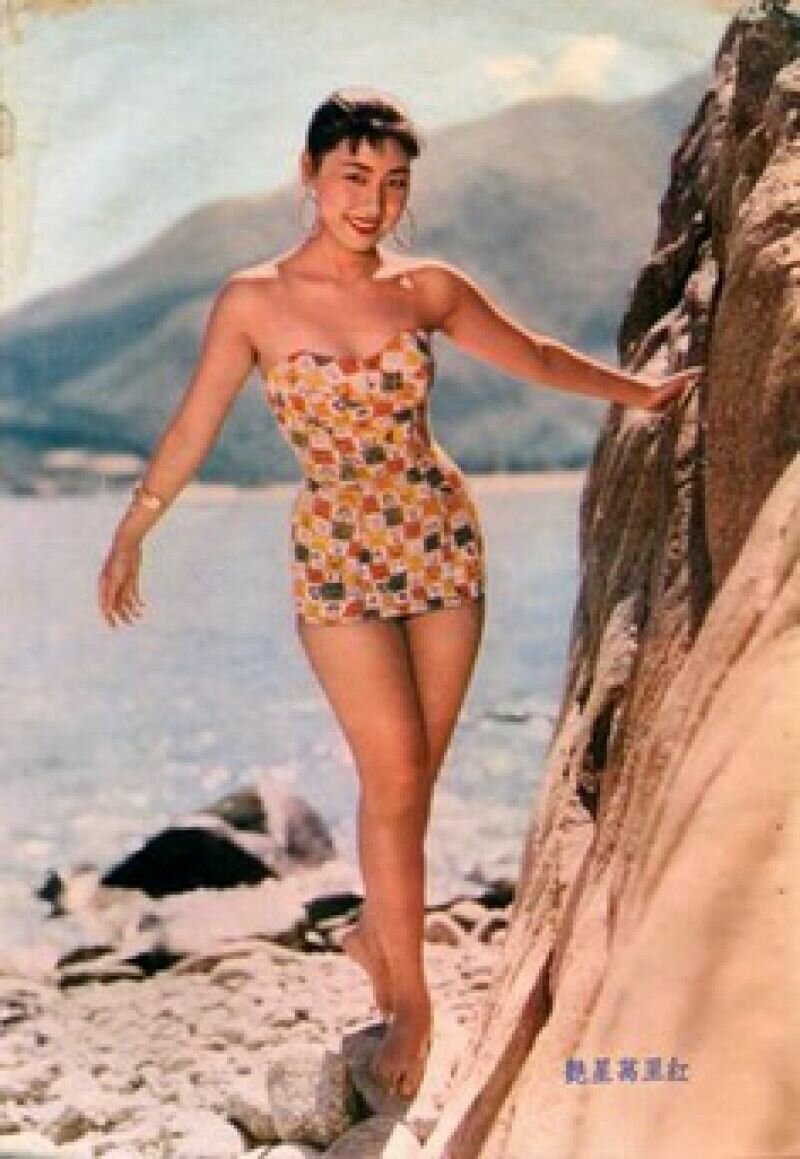

It’s Saturday night and the place is packed. They’ve put me in the corner for lonely strangers with the fish tanks and the Asian pin-up posters. I cannot see any of the other customers. I can only hear the different French conversations. I try to make out what it is they are saying, but my French is bad, and four or five conversations are taking place at the same time. I decide to stop understanding and I start relaxing. Now it’s just a comfortable sophisticated French blur.

I drink my beer and wait for my duck and asparagus.

At certain points during my meal all conversations die out at the exact same moment. The sudden unplanned quietude shoots me back to a high school party in an indoor swimming pool: I’m shouting in a girl’s ear, hoping to impress her with a well made-up story. When suddenly the music stops, the silence alters the atmosphere entirely, turning my words into ridiculous sounds, making me feel like a fool.

But tonight I enjoy these ‘in between moments’ since I’m not planning to say anything to anyone, except ‘Avez-vous chopsticks?’

This text is a fragment of Het is begonnen. Onderweg met Georges Perec (It Has Started, On the Road with Georges Perec). It consists of 11 texts, all of them prefaces to a possible research into the connections between the writing experiments of French novelist Georges Perec and practices in visual art, concentrated on Sander Uitdehaag’s own work and life. The prefaces are very diverse in style and content and can read in random order, and together make up a meta-story: a search for the right tone and the best beginning.

Het is begonnen is for sale via .