Less is better, less is more. This principle has held the last century's art in a tight grip. Even now, the elimination of frills and the absence of the anecdote remain praised and encouraged by the majority of art critics and art tutors.

A lengthy history precedes the art of omission. Remarkably, the roots to this aesthetic approach lie in the Baroque; age of decorum, extravagance, excess, and the ornament. But this same seventeenth century period also gave way to a break in the tradition of following a narrative and by representing it scene after scene, like in a comic strip. The Baroque celebrates the climax and the apotheosis; that one instant in which an entire story is condensed into an ultimate moment of theatricality, frozen in time.

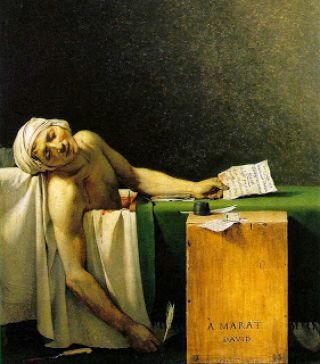

In 1793, the art of omission encountered a curious development in the form of the French painter Jacques-Louis David. His ‘Death of Marat’ is a world famous masterpiece, an icon of the French Revolution, an unequivocal image of devotion inspired by the events that instigated the uproar in Paris on July 13th, 1793 when a young woman of twenty-four named Charlotte Corday from Normandy murdered the Jacobin revolutionary leader, Marat. David’s idiosyncratic depiction of this scene might be considered religious and engaged rather than factual or pragmatic.

Jacques-Louis David

Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ inspired David’s brilliant depiction of Marat’s dangling arm. His ability to isolate this motif was genius. No painter before him had brought an arm to light in the same dramatic way.