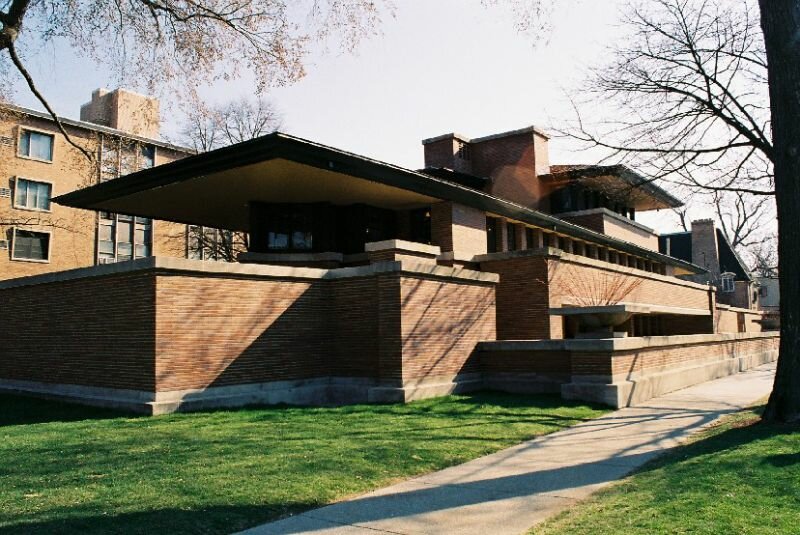

Frank Lloyd Wright built the Robie House in an era where the Internet did not yet exist and travelling was still a true adventure. During an excursion through Robie House, a guide told me that after the house was finished and inhabited, Frank Lloyd would often visit to make sure that the furniture hadn’t been moved. He had designed the house, including the furniture, on the basis of his own ideals of how to optimally live in the space. Ikea’s slogan, are you just living or are you alive (woon je nog of leef je al, translated from Dutch), might very well have originated here. In light of the social relations and available knowledge of his time, F.L. showed an incredible, arguably dictatorial, commitment that surpassed the responsibility of designing a house. F.L. developed an entire concept and assumed responsibility over the lives of the inhabitants by being the director, as it were, of their domestic space.

A hundred years later, the Robie House is a museum and the status of the architect has shrivelled to a consumer of projects. Projects that comprise of little more than designing the money flow controlled by banks, insurance companies and project developers. During these hundred years, capitalism underwent a transformation that is reflected in the profession of the architect. The last decades of the previous century saw modern social capitalism exchanged for a predatory capitalism that, within current globalisation, is developing into brutal indulgence capitalism. McDonalds is recycling, Shell makes use of clean energy, and the Rabobank is sustainable? On paper, global problems like climate change are being braved with technological marvels. If we were to combine all the energy networks of the world or connect wind turbines in the North Sea to solar panels in the Sahara, we would have constant access to energy produced by the sun, wind, or water. Or, if we stack pigs in high-rise buildings, they could always roam free.

Of course, these plans still need to be conceived of, designed, and developed, but that should be allowed in today’s polluted conditions. A better world begins tomorrow.

Frank Lloyd Wright also had grand ideas. Broadacre City, for example, was the manifestation of his vision of a society where individual happiness was found in and around the yard. Technology was subject to this form of social living. What is most fascinating about this is not the technological aspect, that’s merely development done by engineers. What is particularly admirable is the engagement with which he applied his ideas in daily life. Moving around furniture in a house where the inhabitants have long moved in, can you imagine? In my thoughts, I can see Frank Lloyd walking past Broadacre City’s vegetable garden with a hoe, a straw hat on his head, pushing a wheelbarrow before him, checking all around to make sure there aren’t any weeds growing among the potatoes, that the beanstalks are neatly lined up, and that the chickens are clucking about happily.

What does this sort of engagement entail today? Rem Koolhaas sailing over the North Sea to turn the turbines himself to face the wind, or a Winy Maas feeding pigs on the 27th floor of pig city? These images don’t quite conjure the same romantic engagement as a hundred years ago. Nowadays, all global injustice is uncovered with a click of the mouse, rendering all form of engagement implicitly insufficient. We should also check building sites for slave labour or child labour, for working conditions, the building materials for how they’re produced and their origins, the waste, the air quality, the food, the money flow etc. It’s an impossible task that the current management society would rather “outsource” to external experts. As a result, even our responsibilities have become commodities. In order to reach a new Utopia, the architect must, as an independent thinker, free himself from the prison that he has locked himself in as a consumer.

An independently thinking architect takes responsibilities himself; an independently thinking architect practices insourcing. The “Moral Balance Sheet” is an experiment to apply the wide definition of prosperity to the architect’s practice, an experiment to locate one’s own responsibility and to take it. A Ton Matton, who produces his own energy, wears second hand clothing, slaughters his own chicken, and plants a tree himself. The tree is a beech tree, planted on my yard. This tree absorbs more carbon dioxide than is needed to write this article. But for every Google search, the same amount of energy is used as for a car to drive 400 meters. Should we wait around to see how many hits there will be and how long that tree will have to grow for it?