Title card of the movie TENSION

The following is an introduction to a lecture about systems from the programme of the Studium Generale. During her talk, she speaks about the difficulty of speaking of language through language, since language is a system in itself.

This lecture is impossible. Remaining silent might be the better option. Speaking, or rather: language as a system. My speaking, thus, undermines, with each word I utter, the subject that I’m tackling: systems. In other words, how can I speak of a system while I speak using a system? Which language should I use? There is no way to create distance from the subject. I’ve lost my credibility. My talk is in vain, my presentation is a failure before I’ve even commenced.

Where to begin? Par où commencer? Waar moet ik beginnen?

[Tine Melzer/Kasper Andreasen]

Structures and systems are not immediately visible, Roland Barthes wrote in Writing Degree Zero in 1953. They’re impossible to immediately comprehend, it’s hardly possible to distinguish or name a system in one glance. You won’t automatically discern the systematic characteristic inherent in an object or phenomenon. “Everything has a schedule, if you can find out what it is,” according to the American poet John Ashbery. The school is a system. As we stand here, we form a system. Even the jumper that you put on in the morning is a system, but you’re hardly aware of the pattern that lies at the foundation of that system. You didn’t stop and ponder the production process that produced your jumper. Or the advertising campaign where your garment featured. Or the system that shaped your sweater: the system of yarn and needles, hours of patience, cups of tea—that is, if it hasn’t been machine produced. You didn’t think of your jumper and it’s place in the ever fickle, but ultimately systematically developing system of fashion. Although initially completely invisible, a long history of colour, material, and design precedes the existence of your sweater. As you can see, we’re initially oblivious to the countless systems inherent to products and objects. We only recognise patterns and system on second glance.

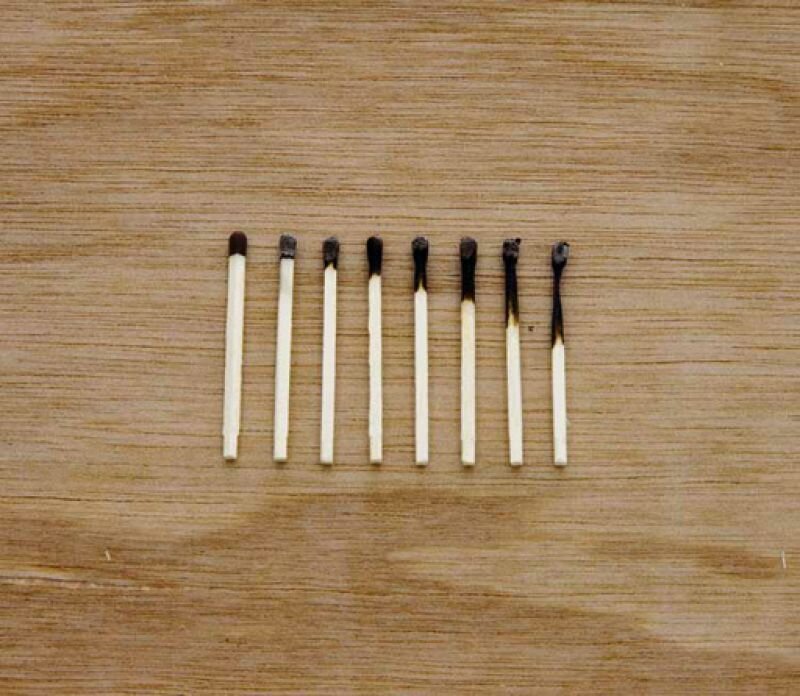

It’s not always easy to know whether systems are intentionally put in place by their maker. Does the system lie in the “eye of the beholder,” or does it lie within the object? Hanne phoned me a few weeks ago, asking me if I would do a talk on systems. At that moment, AfterGlow, an artist publication by Navid Nuur was laying before me. While I spoke to Hanne, the little magazine stared back at me: on a photograph, eight matchsticks were laid out on a tabletop, their heads charred to greater degrees. Or, you could see the heads as portraying a downward slope. It all depends on how you look at it. During our phone call discussing systems, I suddenly noticed the horizontal wood grain of the table top on the photo, through which the vertically placed matchsticks created a rhythmic grid.

2004-2010

matches

courtesy Navid Nuur and Martin van Zomeren, Amsterdam

I wasn’t sure if it had been the artist’s intention to incorporate this last system of horizontal and vertical lines into the image. Was it an intentional grid, had it been inserted consciously or unconsciously? Was it a consequence of the first system I’d perceived of rising and falling diagonals within the image? Or was seeing a grid the logical consequence of my dialogue with Hanne, in which we spoke of systems within artworks? You know the phenomenon: think of the colour red, and the city seems doused in red.

“While I spoke to Hanne, the little magazine stared back at me: on a photograph, eight matchsticks were laid out on a tabletop, their heads charred to greater degrees.” After I’d noted the sentence, I changed, as a variation on my own wording, the word “matchsticks” to the more poetic, but also more precise “wooden slots.” And as soon as I’d named the wooden quality of the matchsticks on the photo, they began to create a wondrous similarity or contrast to the wooden backdrop they were laid out on. Or was the table a laminated surface, onto which a fake depiction of wood was printed? I suddenly saw the image in a different context. It began to move. Or was the similarity or contrast to wood only textual merely because I named it, because I wrote about it?