The immense hangar, an old converted bread factory, is lined with market stalls where families sell their old wares: junk that, pulled from the bottom of cellars and the dark corners of garages and cupboards, momentarily regains value, however slight. Hands grope through second hand clothing, mostly chain bought and cheap, grouped in slightly musty smelling endless piles.

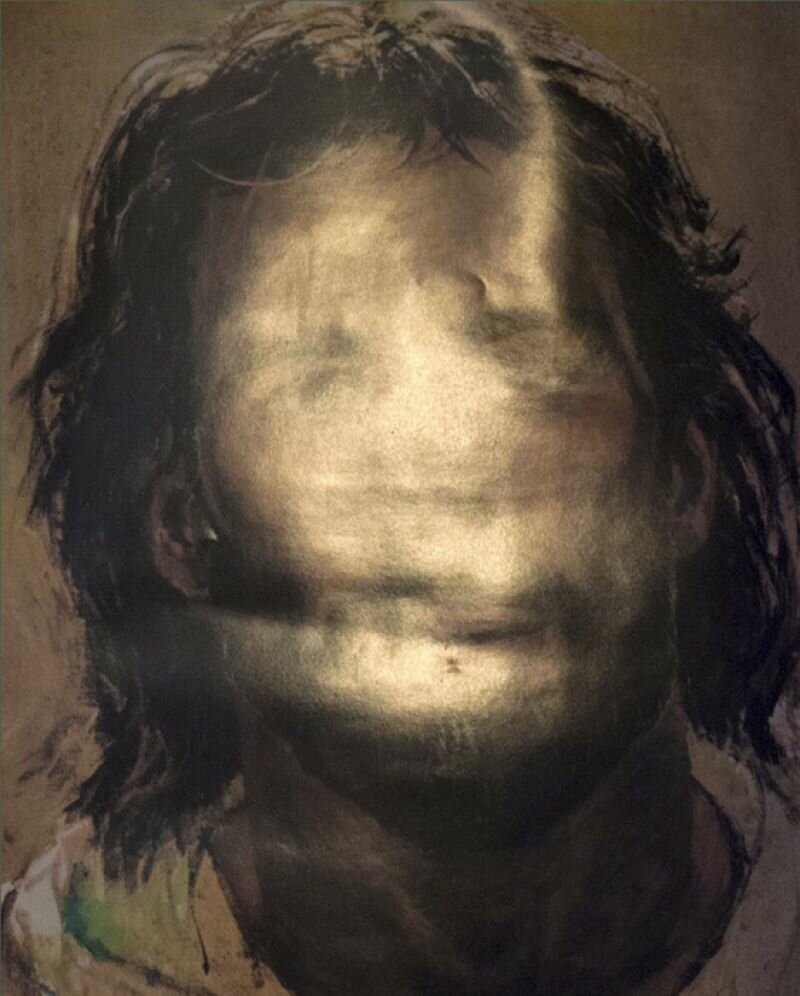

At the far end of a table covered in yellowing art books, old editions of classics frayed at the edges, and stacks of thriller pulp, sits a large folder. It opens to a collection of drawings, watercolours and sketches that are mostly abstract and frantically scrawled. I look up and catch the gaze of a tall, melancholy man with long mousy brown hair and silver rimmed circular spectacles. With a nervous excitement, the seller explains that these are the remains of his artist days that he sells alongside the used books. I buy an odd, demonic depiction of a creature drawn with Indian ink over a printed pencil drawing.

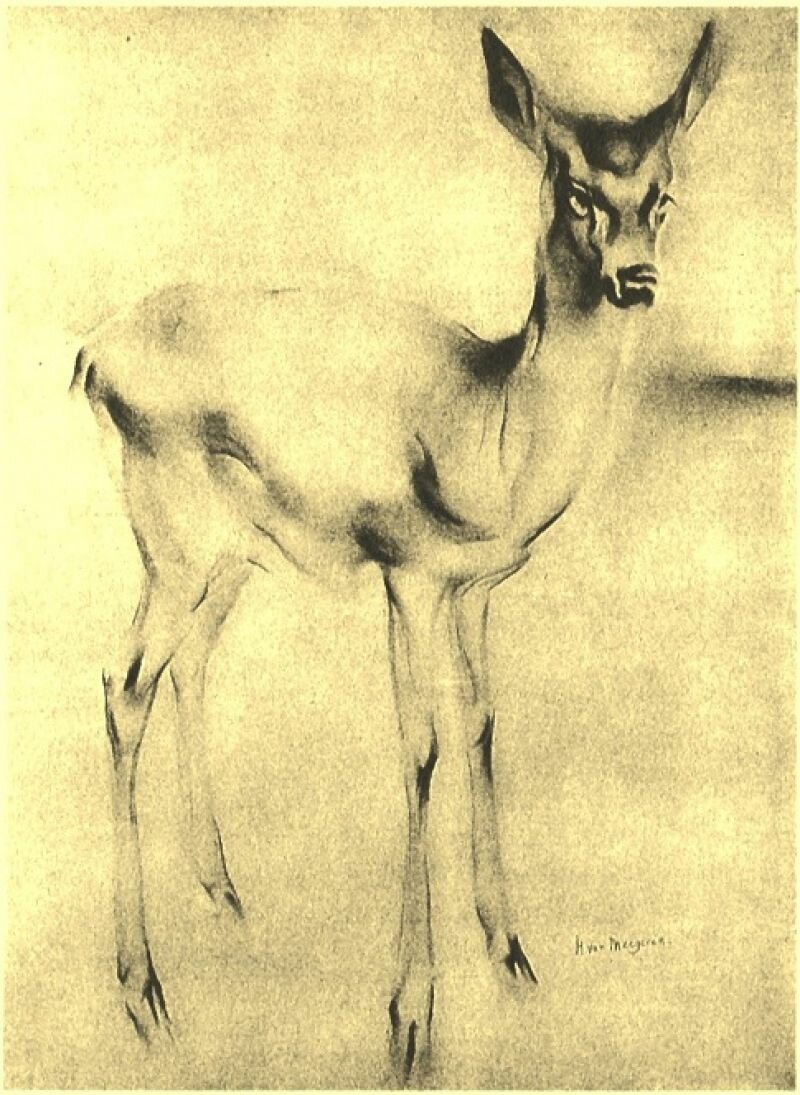

One late night sitting around my dinner table, a friend notices the ink drawing on the wall, and after taking a closer look, asks if it’s a genuine Han van Meegeren, the great master forger. As it turns out, the backdrop to the demon creature is a copy of Han van Meegeren’s most prolific pieces, namely ‘Hertje’ (or ‘Little Deer’), reproductions of which hung on the walls of thousands of Dutch homes in the 1920’s. But van Meegeren’s style was caught in the past and completely irrelevant in a world of Cubism, Dadaism, and Surrealism, and he was derided by the art world for his lack of originality.

At the start of the 20th century, detecting a forged painting was a fairly simple process: a swab of alcohol was wiped over the dubious canvas, a needle carefully inserted and checked for any oily residue. This would be the mark of a forgery, as an age-old canvas would be thoroughly hardened and deliver a clean needle.

Han van Meegeren bought cheap 17th century paintings to scrape off the original painting. Instead of oil, he used an early form of plastic named Bakelite to mix his pigments into paint. He would then bake his freshly painted antique canvas until the plastic fully hardened, and finished the simulated aging process by rolling the canvas and cracking its surface. Voila, instant Dutch Master!

Relatively few paintings by Johannes Vermeer have survived the ages. When in the 1930s a series of paintings began emerging from his supposed unknown religious period, they were eagerly snapped up by collectors, including the Rotterdam museum Boijmans van Beuningen, who paid what would today be more than 4,5 million Euros for Vermeer’s Supper at Emmaus. The painting, revered by art critics as Vermeer's masterpiece, was nothing more than a carefully executed van Meegeren.

Having foiled the art world that rejected him, van Meegeren lived a wealthy and lavish life all through the Second World War. But his life of decadence was disrupted when, after the end of the war, a Vermeer was found in Nazi henchman Herman Göring’s largely misappropriated art collection, and was traced back to van Meegeren, who refused to name his source. The outrage was immense: how dare he allow Dutch national treasure to fall in the hands of a Nazi? He was arrested for treason, a felony that at the time was punishable by death.

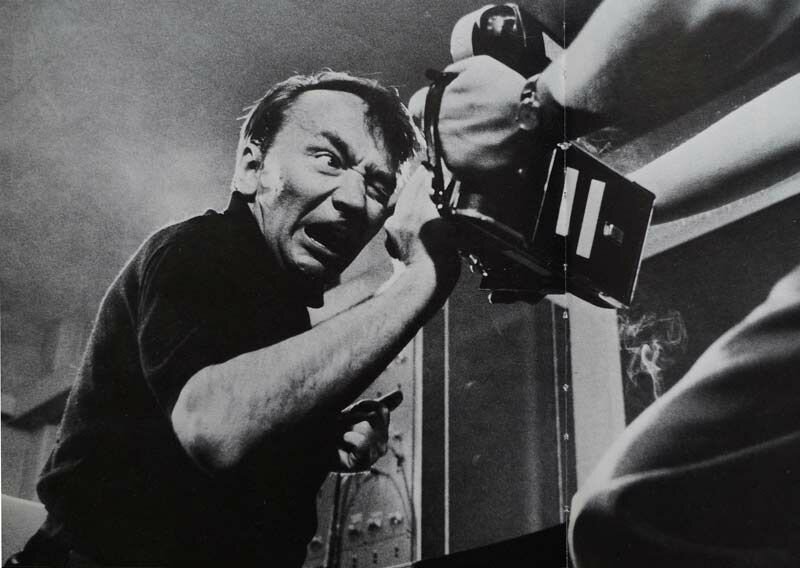

His plea to innocence was simple. He couldn’t possibly be a traitor, because the painting he had sold to Göring was not a Vermeer, but a forgery by his own hand. A sensational trial was carried out in a courtroom hung full of van Meegeren’s fakes. The art world was stupefied – how could they have been so utterly mistaken – and he was deemed to be a liar.

As a free man, Van Meegeren passed away from a heart attack before he could begin his prison sentence, and after his death, his paintings became so desired that van Meegeren forgeries began to flood the market.

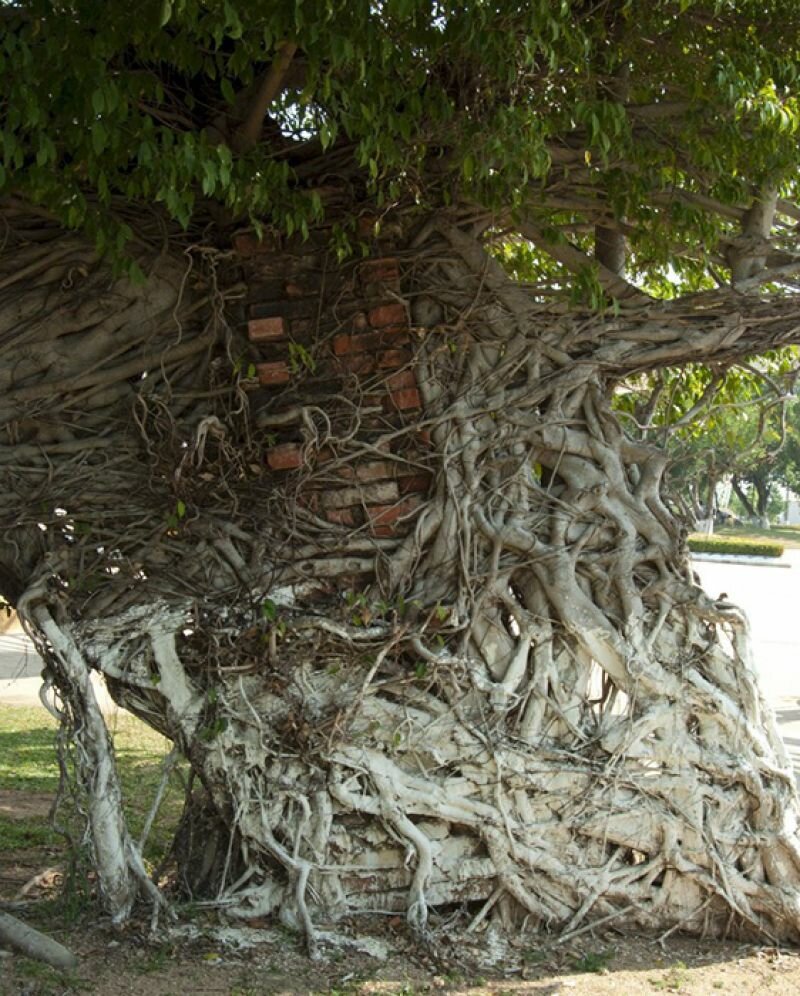

My own Hertje still hangs on my wall, covered by the market man’s inky black drawing. Is he still no longer an artist? A failed artist can become a most tragic creature, overcome by vanity, envy, and consumed by bitterness. But Han van Meegeren’s exclusion from the art world led him to what is probably the most extensive art scam ever. “But sir, I'm sure about one thing: if I die in jail they will just forget all about it. My paintings will become original Vermeers once more. I produced them not for money but for art's sake.”