Paul Pieroni (UK) is exhibitions curator at SPACE in London.

P

Paul Pieroni

SPACE

12.05.2014

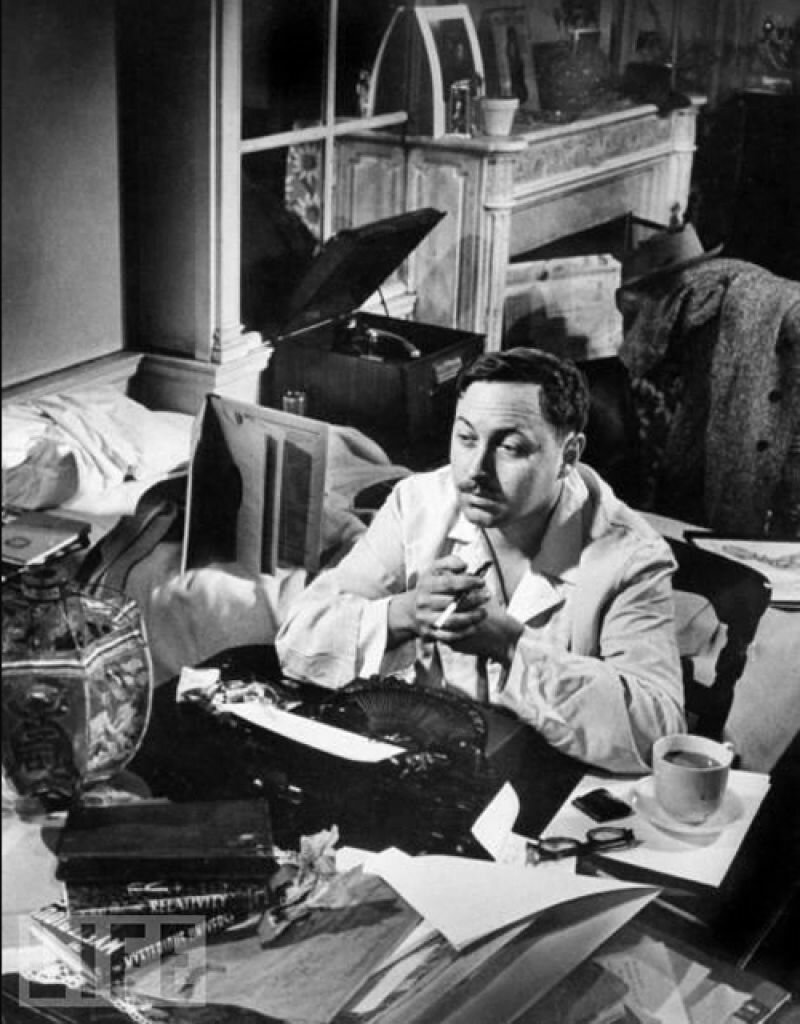

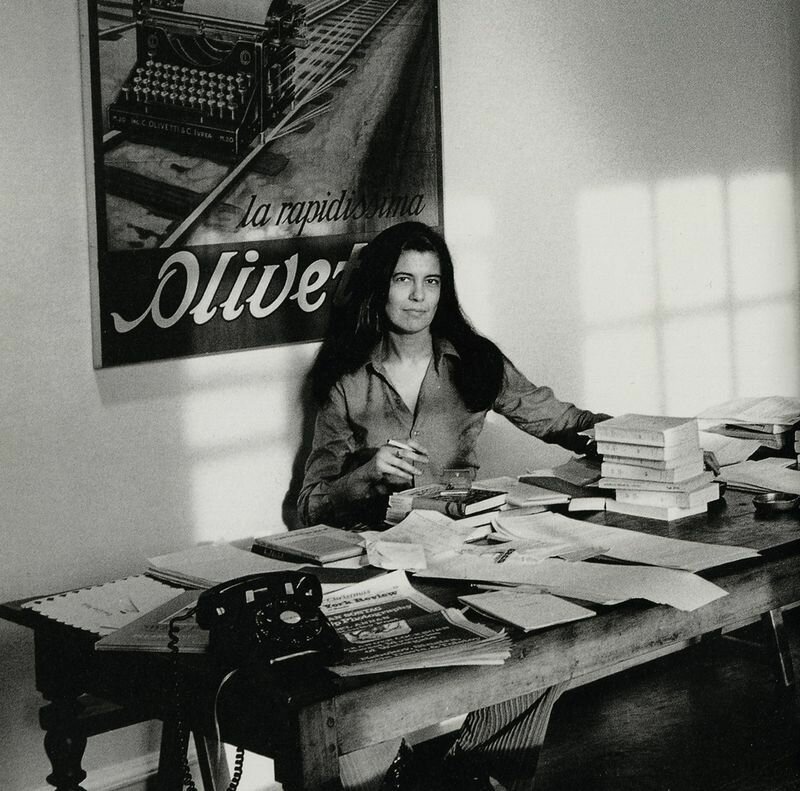

Susan Sontag

I keep this document. It's sort of a list actually - a list of things that people have said about 'how to write'. In the main what people have said is severed from who they are. Indeed I'm not really sure who said what anymore. I know there is a fair bit from Reader's Digest 'how to be published' columns (always really good advice). A long list from Walter Benjamin, also, which is kind of terrible and kind of brilliant at the same time. What else? A nice set of tips put together by students of W.G. Sebald after he died; lessons from his final classes - again all good stuff, a few scraps from various October school theorists and - I guess - some stuff I made up.

When I'm writing, which is to say struggling, I print out this list and keep it next to me. Upon encountering one or another impasse, I'll often just reach for it, scan it a little. Something of use usually pops up. A rudder then, this list. Something that steadies. I pass it on here. Feel free to add to it. The entries are unnumbered and should not be considered hierarchical. Best thing is to add and delete as required.

HOW TO WRITE

+ Add loads of details. Do NOT be vague. Add dates, spatial / environmental info, etc.

+ Don't be florid: keep it clear, precise and powerful.

+ Make every word necessary. When we rip away all the passive and wordy phrasing, we get an easier-to-digest sentence

+ This is meant to feel and be hard.

+ The best writing is understated, not full of flourishes and semaphores and tap dancing and vocabulary dumps that get in the way of the story you are telling. Once you accept that, what are you left with? You are left with the story you are telling.

+ The story you are telling is only as good as the information in it: things you elicit, or things you observe, that make a narrative come alive; things that support your point not just through assertion, but through example; quotes that don’t just convey information, but also personality. That’s all reporting.

+ As the note taking stage nears completion read them carefully then lock them away and don’t look at them again until you have a first draft. This will help you craft an ideal story.

+ All stories are ultimately about the meaning of life, when writing an article persuade yourself of this, understand that it must be about something larger than itself—some universal truth—and begin to search for whatever that is. Sometimes, midway through, you realize it’s not what you thought, it’s something else. But, to quote Roseanne Rosannadanna: “ … It’s always something.

+ Talk about what you have written, by all means, but do not read from it while the work is in progress. Every gratification procured in this way will slacken your tempo. If this regime is followed, the growing desire to communicate will become in the end a motor for completion.

+ In your working conditions avoid everyday mediocrity. Semi-relaxation, to a background of insipid sounds, is degrading. On the other hand, accompaniment by an etude or a cacophony of voices can become as significant for work as the perceptible silence of the night. If the latter sharpens the inner ear, the former acts as a touchstone for a diction ample enough to bury even the most wayward sounds.

+ Consider no work perfect over which you have not once sat from evening to broad daylight.

+ Let no thought pass incognito, and keep your notebook as strictly as the authorities keep their register of aliens.

+ The work is the death mask of its conception.

+ Keep sentences short. Might a long sentence be more effective if cut into two? Shorter sentences read quicker. And keep your prose punchy. Re-read your copy to see if words can be omitted.

+ Don't try and be clever and be clear.

+ Writing must come first. Before cycling even. You must be ruthless. The 1.5 - 3 hours that follow a good 8-hour sleep are the most productive time for you. THIS COMES FIRST.

+ Krauss: “the meander” --- you can go anywhere with writing. Be irresponsible.

+ Hal Foster: keep your sources tight. Work from very few; know them well.

+ Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

+ Every sentence must do one of two things — reveal character or advance the action.

+ Start as close to the end as possible.

+ Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

+ Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves.

+ Writing is about discovering things hitherto unseen. Otherwise there’s no point to the process.

+ By all means be experimental, but let the reader be part of the experiment.

+ It’s hard to write something original about Napoleon, but one of his minor aides is another matter.

+ You need to set things very thoroughly in time and place unless you have good reasons [not to]. Young authors are often too worried about getting things moving on the rails, and not worried enough about what’s on either side of the tracks.

+ A sense of place distinguishes a piece of writing. It may be a distillation of different places. There must be a very good reason for not describing place.

+ Meteorology is not superfluous to the story. Don’t have an aversion to noticing the weather.

+ It’s very difficult, not to say impossible, to get physical movement right when writing. The important thing is that it should work for the reader, even if it is not accurate. You can use ellipsis, abbreviate a sequence of actions; you needn’t laboriously describe each one.

+ ‘Significant detail’ enlivens otherwise mundane situations. You need acute, merciless observation.

+ Oddities are interesting.

+ Characters need details that will anchor themselves in your mind.

+ Get off the main thoroughfares; you’ll see nothing there. Kant’s Critique is a yawn but his incidental writings are fascinating.

+ There has to be a libidinous delight in finding things and stuffing them in your pockets.

+ You must get the servants to work for you. You mustn’t do all the work yourself. That is, you should ask other people for information, and steal ruthlessly from what they provide.

+ I can only encourage you to steal as much as you can. No one will ever notice. You should keep a notebook of titbits, but don’t write down the attributions, and then after a couple of years you can come back to the notebook and treat the stuff as your own without guilt.

+ Don’t be afraid to bring in strange, eloquent quotations and graft them into your story. It enriches the prose. Quotations are like yeast or some ingredient one adds.

+ Every sentence taken by itself should mean something.

+ Writing should not create the impression that the writer is trying to be ‘poetic’.

+ It’s easy to write rhythmical prose. It carries you along. After a while it gets tedious.

+ Long sentences prevent you from having continually to name the subject (‘Gertie did this, Gertie felt that’ etc.).

+ Avoid sentences that serve only to set up later sentences.

+ Use the word ‘and’ as little as possible. Try for variety in conjunctions.

+ Lots of things resolve themselves just by being in the drawer a while.