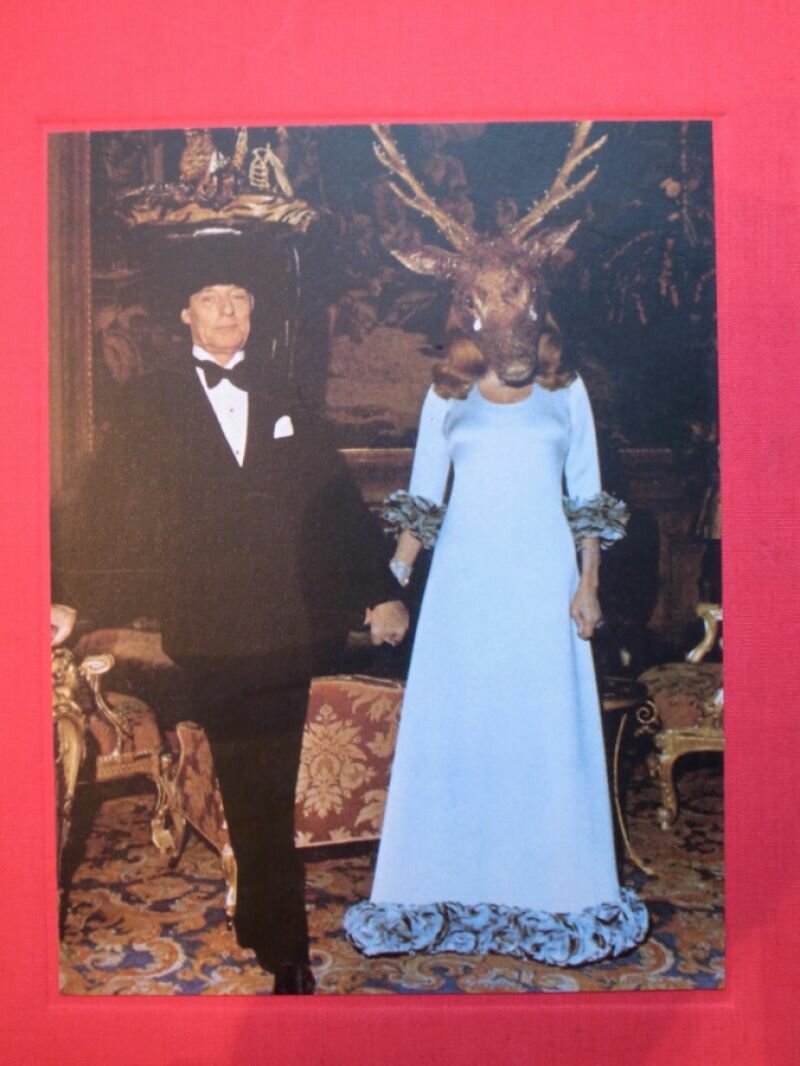

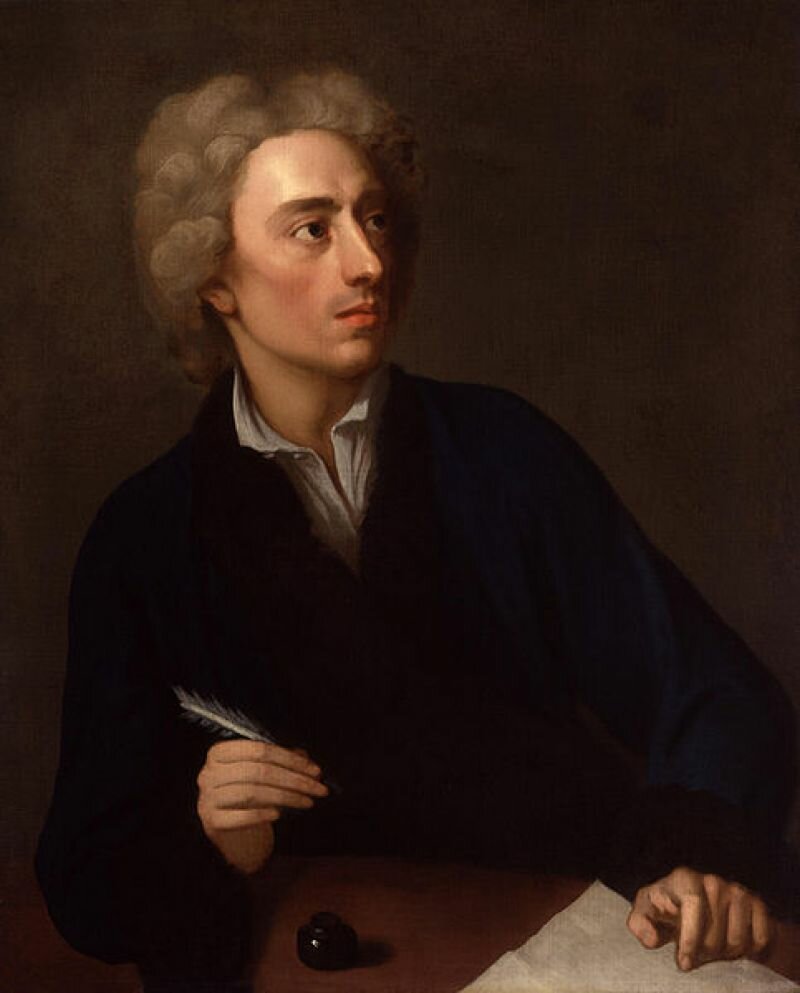

English poet and satirist, never grew beyond 4 ft 6 in (137 cm)

Ladies and gentlemen, little artists!

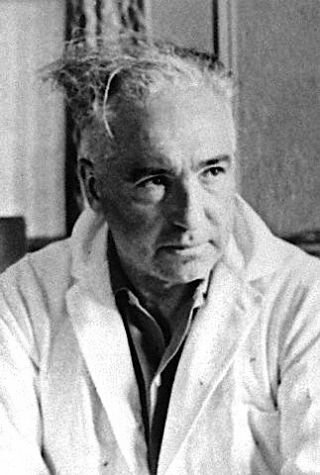

When I was asked to speak to little artists today, I immediately thought of Wilhelm Reich. Rede an den Kleine Mann (Listen, Little Man!) leapt from the deep recesses of my memory. It had been years since I’d thought of this text, the heart-cry of a Polish-Austrian sex therapist. It wasn’t so much the starting point of the text (the little man suffering under the big man,) that made an impression on mebut rather its approach. By speaking directly, man-to-man, Reich ingrains into the little man that his trivial life of servitude is wholly self-inflicted.

Little man! Reich calls out, you close your eyes because you’re frightened to death of how small you are, you despise yourself and are most at ease in the role of the beloved slave. You’ll take what you’re given, but you, you only give what is demanded of you. The truth irritates you, and you dislike those who strive for freedom. Instead, you spend all day practicing life tactics. You don’t believe that anyone sat at your table could ever be capable of achieving greatness, yet you’ll believe what you read in the paper without scruples. If you were given the choice between a visit to the library or witnessing a fight, you’d choose to see the fight. And of the big men, you don’t see the truly big men, just the quasi-big who surround themselves a lot of little ones. “Rede an den Kleine Mann” continues on this tangent throughout the whole text. Reich empathises with the addressees because within him, too, resides the little man. However, he sees no worth in half-hearted methods and so he positions himself as a severe yet just father. And that’s just as well, because Rede an den Kleinen Mann thanks its quality to this strictness, despite it hardly being read anymore now that the little man is near extinction.

How different the situation is for the little artist is! The little artist truly is alive, and speeds himself to the auditorium when he hears of a talk especially for little artists.

Alexander Pope, smallest poet ever

English poet and satirist, never grew beyond 4 ft 6 in (137 cm)

Little artist! I call out, every dream of a becoming a grand artist will be met with a hundred cold showers! It’s far easier to rid yourself of the little man in you than the little artist. The little woman in you can be made into a hundred big ones, but the little artist in you won’t ever even be made into one big artist.

Do you remember, little artist what you said at that party, on the boat, after your graduation? “Now I’m an artist,” you said, with that strange combination of self-ridicule and pride. The relativity of your words was obvious, the realisation that this was only just the beginning, that the word artist was still too pretentious and that you only meant it in the sense of the comedian, the singer of songs, the actor in the cabaret. At the same time, you sounded so sure of yourself, as though you’d already moved on and only spoke in literally translated English sentences like “Now I’m an artist.” As if you’d mentally crossed the borders of this puny Dutch city-state, and were already well on your way to becoming a global artist.

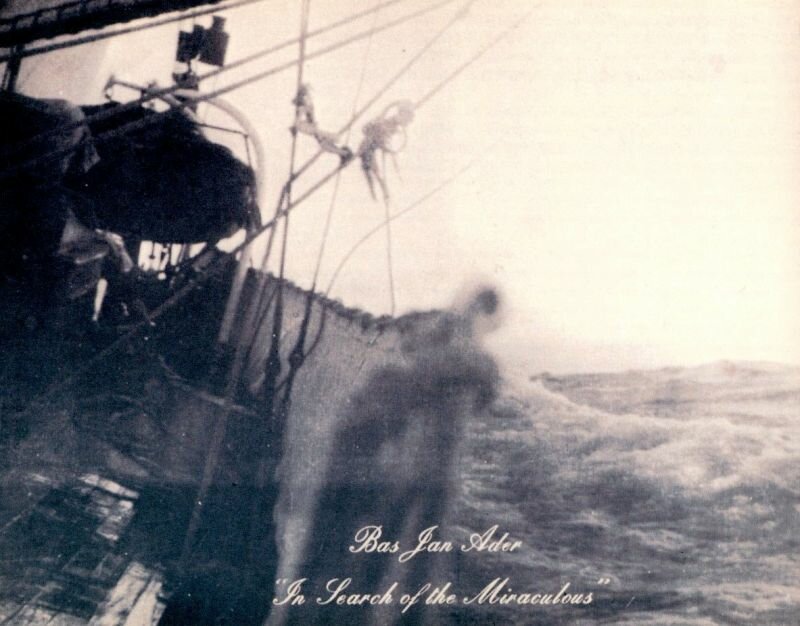

This conflict you showed there, dear little artist, is not coincidental or only applicable to you; it seeps through all that is art. There’s the little art, the drudgeries that are mocked, cursed and hushed; and then there’s the big art, declared holy to the extent that it’s beyond reach. The no man’s land between the two is vast as an ocean and impossible to oversee in its totality. The one art is seen as absolutely worthless, and any investment in it seen as money wasted. And the other art is so costly that the even the largest fortune pales in comparison.

You, little artist, might try to cross that ocean in a rowboat. But even if paradise descends on Earth, you’ll still have to make do with what you have as a little artist. You’ll always be kept little with an iron fist without mercy, without sympathy. Herein lies the difference between the little artist and the little man. The little man stayed little because he was poor and powerless. He was able to climb up the ladder, pull himself together, and expand his power and market value. In this way, he could overcome the little man in him.

English poet and satirist, never grew beyond 4 ft 6 in (137 cm)

Little artists, on the other hand, will never be able to overpower the little artist in them. They'll stay little forever, because they have to start all over again with every new artwork.

True art is invented artwork by artwork. Art refuses to climb, is indifferent towards power, and refuses to pull itself together. Those little artists who think themselves capable of influencing their own market value are victims of the Great Postmodern Misunderstanding that claims artists to be tradesmen.

Not a hundred workshops in art management, nor a hundred networks, oh little arts, can exceed your market value past the size of a lottery ticket; only the lottery owner and the notary could influence it. Little artists who can't understand this haven't overcome the little man in them yet. The little man did useful things, these useful things could be magnified and used in transactions.Art, however, is of no use. Useful art is not art.

Nevertheless, from time to time, a little artist in his rowboat will unexpectedly arrive at the shores of the big art. After all, the prize money has to fall at some point on one out of every hundred thousand lottery tickets. But generally speaking, the little artist will have to rack himself just like the little man: he'll have to slave away, to sweat, and to toil. For eternity, because the little artist will never disappear. That's just the way it is, the little artist will suffer forever and ever. And all this suffering is no guarantee for great achievements, however much a pity this may be for the Tenacious Romantic Misunderstanding. The one that says that blood, sweat, and tears suffice to make an artwork regardless if no one sees it, understands it, or buys it.

Little artist! No life is more frustrating, thankless, yes, inhumane than yours! You're at the very bottom rung, holding on to the top and there's absolutely nothing in the space between. All that keeps you going is hope, "hope, the wings of all time," as the little poet says. But hope for what? Don't say you hope for greatness, dear little artist; or worse yet, that you hope for fame. You cannot strive to be great, greatness emerges all on its own. Instead of trying to defeat the little artist in you, you're probably better off dispelling the great, famous artist stuck inside your head.

All you can really want is to live for art, to work, to make something, then make something better, invent an artwork, and then invent another artwork. The only thing you have to want, is to want to know. Wanting to know, knowledge, the rest is irrelevant. The nature of that knowledge or where it comes from is irrelevant. There's as much to learn from a good fistfight as there is from the library.

The legendary world champion boxer, Muhammed Ali, once delivered a speech to the students of Harvard University. He said: 'In my own way, I've studied a whole lot. But that's not what people pay for, people pay for follies. The wise man can play a fool, but the fool can't play a wise man. I play a whole lot."

Please understand little artist, Muhammed Ali, he’s a great artist,..