Felix Gonzalez-Torres: When people ask me, “Who is your public?” I say honestly, without skipping a beat, “Ross.” The public was Ross. The rest of the people just come to the work.

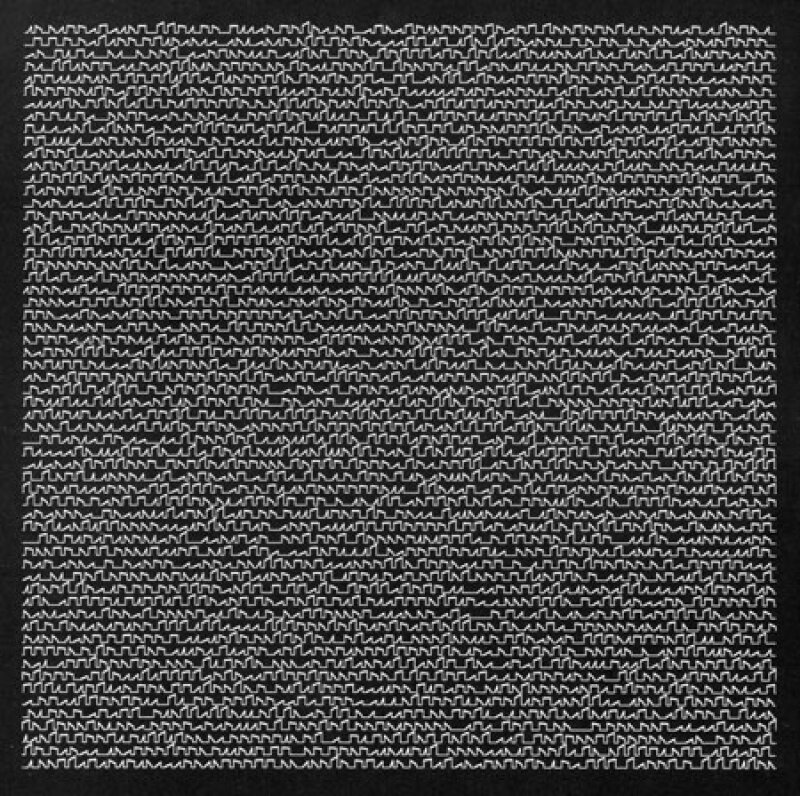

Ross Lalock was Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ partner. When the doctor diagnosed Ross with HIV, he assessed his ideal weight to be at175 pounds. Portrait of Ross is precisely that: 175 pounds of candy collected into a mound. By the invitation to take one of the candies, the viewer becomes part of the work and becomes more than simply a viewer. Every morning, the mound is replenished until it’s back at its ideal weight.

These candies are not only a representation of Ross’s weight, but also one of his struggle against the illness. HIV emaciates its patient, but the weight of the soul remains the same and allows for the patient to carry on, day after day.

Each day, the work risks being reduced to absence as the mound dwindles to nothing and no candies are left, in which case the viewer would be responsible for the lack of an artwork. And every day, Gonzalez-Torres plays this game with his audience, allowing them to decide the form of his work. With his work, art becomes fluid and in movement, but also in constant risk of disappearing.

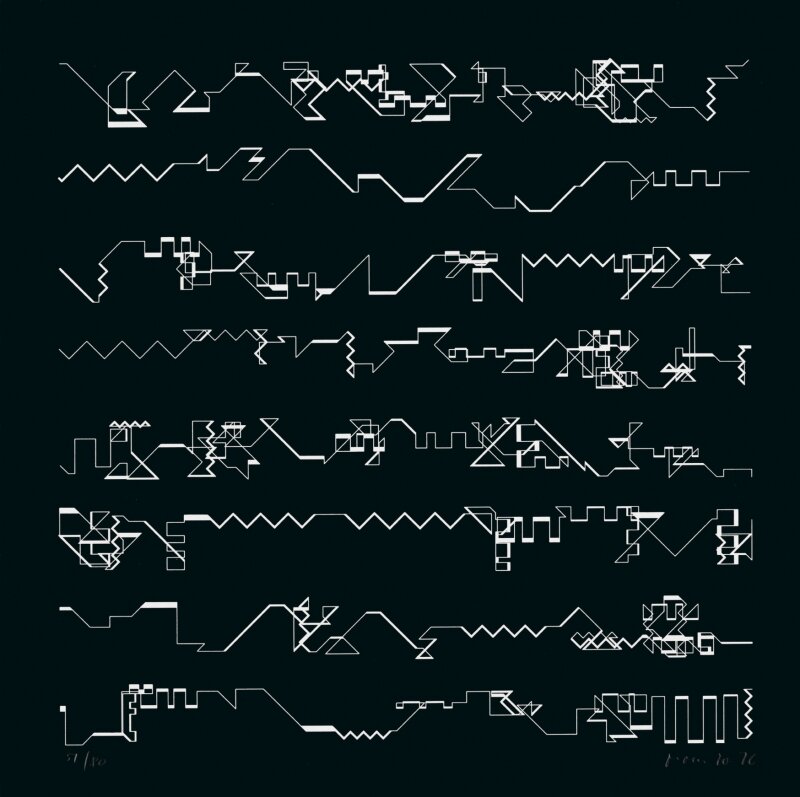

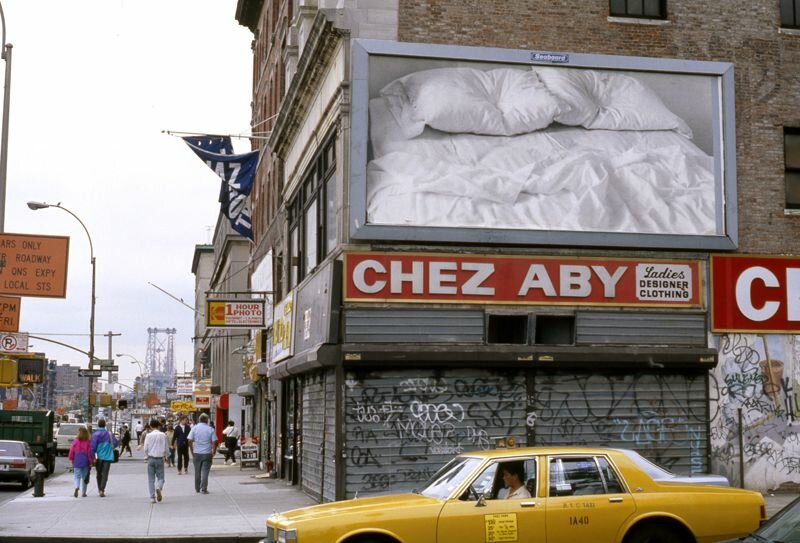

A black and white photo of an empty bed with two pillows. A slept in bed. This is the artist’s own bed. The image was exhibited at the Projects Gallery at the MOMA, as well as on twenty-four billboards around the city of New York: Second Avenue and East 97th Street in Manhattan and Third Avenue and East 137th Street in the Bronx. None of these places were related to the art world of museums, galleries, and collectors. The number, twenty-four, relates to the date on which Ross died.

With Gonzalez-Torres’ sparse and tranquil photograph, the barrage of images that overwhelm New York pedestrians was temporarily paused. No text was supplied to explain the text. And there was no intention, as other billboards typically have, to lure the passerby into buying something. It was nothing more than a photograph of an empty bed with two pillows and a crumpled sheet. An image of private space manifesting itself within public space.

Gonzalez-Torres’ decision to refrain from showing Ross’ image can be seen as a political act. Typically for that time, depictions of AIDS denoted a discerning breach between the homosexuals and the heterosexuals. The sick homosexuals and the healthy heterosexuals. Gonzalez-Torres refuses to depict Ross. With his billboard, Untitled, he depicts the invisibility of the gay community. But he refuses to place himself in opposition to the dominant population, as Robert Mapplethorpe was doing. Gonzalez-Torres invites the viewer, regardless of their sexual preference.

Gonzalez-Torres: Go to a meeting and infiltrate and then once you are inside, try to have an effect. I want to be a spy, too. I do want to be the one who resembles something else [….] We have to restructure our strategies [….] I don’t want to be the enemy anymore. The enemy is too easy to dismiss and to attack.

But Gonzalez-Torres also uses other strategies to include absence in his work. By allowing the viewer to take a part of his work, he plays with the role of the artist and the role of art. The role of the artist as designer, the role of the artwork as form. His work displays and art that is not static, but susceptible to constant change.

Gonzalez-Torres: Go to a meeting and infiltrate and then once you are inside, try to have an effect. I want to be a spy, too. I do want to be the one who resembles something else [….] We have to restructure our strategies [….] I don’t want to be the enemy anymore. The enemy is too easy to dismiss and to attack.

To what extent is it his work?

Gonzalez-Torres:Perhaps between public and private, between personal and social, between fear of loss and the joy loving, of growing, changing, of always becoming more, of losing oneself slowly and the being replenished all over again from scratch. I need the viewer, I need the public interaction. Without the public these works are nothing. I need the public to complete the work. I ask the public to help me, to take responsibility, to become part of my work.