At nineteen years of age, Raymond Roussel worked feverishly at his first grand novel, La Doublure. With great care, he shut the curtains of his study to prevent the light of his genius from escaping through the windows. Above all, Roussel refused to be distracted by the banality of the everyday world. His books were fuelled by nothing more than his endless imagination.

Many contemporary artists are just as fond of hermetically shutting their studio off from the rest of the world. There’s one artist I know who meticulously keeps the sliding doors to his studio, directly annexing his living room, firmly shut. Sometimes, when he leaves the room to fetch a book, I try to peek inside, but it’s absolutely impossible to catch even a glimpse. His scanner is in The Studio. but there’s not a chance in the world that I might make a scan myself, or even to accompany him to the other side of that door while he does it for me.

Having become slightly apprehensive at so much secrecy, I sometimes fantasize about an illegal photographer hiding in there, making all his work. Or that my friend copies all his work from old encyclopaedias or from smutty porn. That’s the great thing about art today, everything can be used as a source, which means that everything is possible.

The studio is traditionally seen as the place from which work originates while at the same time, it’s the prison in which the artist must endure hour upon hour of lonely isolation. Doubt seeps through the walls of the workplace like damp, and the artist asthmatically gasps for air. Every artist in the studio is a lonely hero.

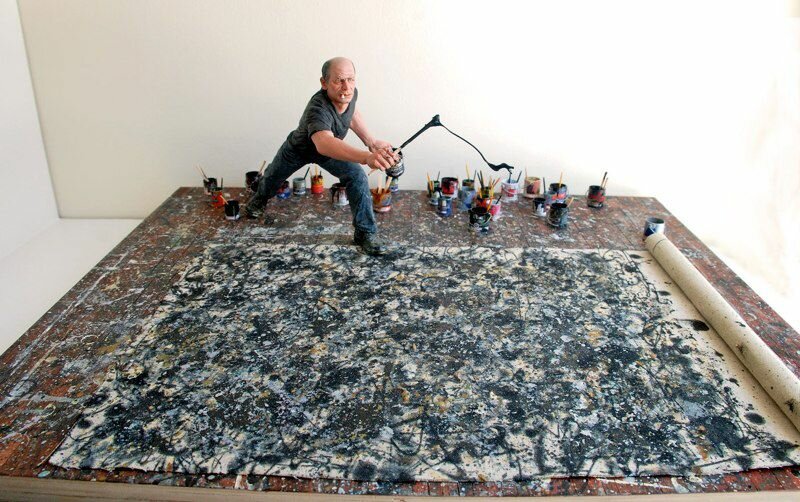

Replica by Joe Fig

Artist Jackson Pollock needed the loneliness of the studio to come to his unique expressive drip paintings. “I am nature” was his response to the artist’s endless attempts at replicating nature. Like a gladiator, he stands in the middle of his canvases, allowing the paint to drip from the stick in his hand. The artist and his work are one. It’s precisely this location, laden with expression and drama, which is seen in replica form in a photo by Joe Fig.

Within the miniature sculpture, the studio is recreated in minute detail (based on Hans Namuth’s photos) and shows the master in the midst of his canvases on the ground, surrounded by paint in shades exactly corresponding the photo. Each detail is correct. The sculptures demand knowledge of the perspective, of the colour, and insight of the artist. Joe Fig’s craftsmanship is praised, and so it seems that a genius is needed to make a perfect copy, However fascinating the work may be, it never quite extends past the original, nor does it exalt kitsch nor the Gepetto-syndrome.

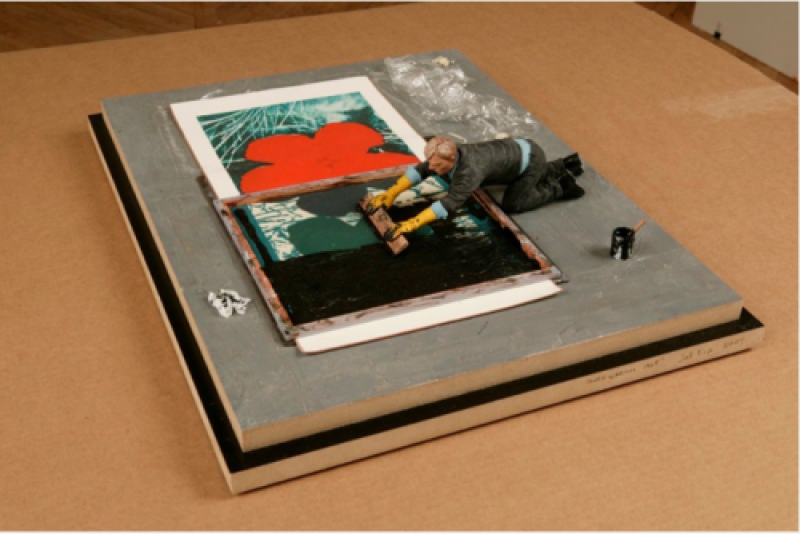

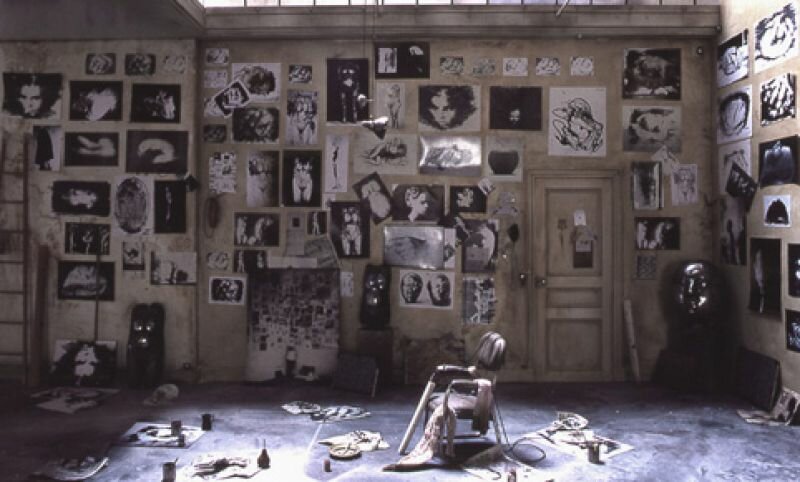

Charles Matton, too, makes replicas of studios and presents them as photographs within a catalogue. His studios are equally miniature and precisely fabricated as Joe Fig’s.

Diorama by Charles Matton, mixed media

Matton wanted to find a modern way to create realistic interiors like the painters of the 17th century, without having to rely on their level of craftsmanship. Initially, he wanted to photograph his friends in their studios and paint over these images. Not too difficult. In the end, he made dioramas in which he carefully made an exact replica of the studio that he photographed. These works were incredibly time consuming and ultimately, the complete opposite of the quick method he initially aspired to. The dioramas were a success (because secretly, everyone loves a doll’s house.)

The dioramas take things a step further because by portraying some sort of primal idea of the sculptor or painter. The spherical sculptures of the modern sculptor fill the space, while in Francis Bacon’s studio chaos prevails. A hippopotamus models in the middle of a studio. These strange boxes, with all their fantasy and precision, explore a world that exists out of our line of perception, even out of our presence.

Replica of Fischli und Weiss' own studio by themselves

Fischli and Weiss also made a copy of a studio, their own studio, in full scale. Everything, even the juice packages have been precisely replicated. Just as painfully exact as Joe Fig. But instead of peering through a keyhole into the artist’s sanctuary, you walk through their reality, their reality which is just as banal as our own daily existence. And it’s exactly this deconstruction of the world and it’s enormous ability to place things into perspective that makes this copy genius.

Instead of locking their doors, Fischli and Weiss invite all to enter their holy land. But there’s nothing left to steal here, they’ve already stolen it themselves.

Replica by Joe Fig

by Charles Matton