The hunt is a symbol of the desire for the One. The hunter appropriates the power to love, to experience total bliss in the ritual. But no matter how beautiful and seductive the game is, the hunt is tragic. Sandor Marai sees his wife as prey, Petrarca regards love as a tasty poison and also for Leonardo da Vinci pleasure and grief are intertwined. Whatever is hunted or seduced, ambivalence always reigns.

A real hunter has a gun. Not a pistol, but a big, long object that kills: a rabbit, a deer, a hare. A hunter is a murderer. The hunt evokes images of a kennel of dogs, hunter’s garments, the scent of forests and wet leaves. A drop hanging from his nose.

This came to mind when I looked at a white dildo-like thing, with a cute pair of antlers at the top that resembles twigs. The white, elongated sculpture has a seam that runs crosswise, which makes it resemble a toy: I was once in the possession of a plastic doll with a crosswise seam. The white renders the sculpture innocent, the shape reminds of a female body with a Bambi-like head. The art work is called Deer Squirrel and is made by New York artist Robert Beck (1959). On the internet one can find a picture of another of Beck’s works, material: gunpowder on paper. A white sheet with gunpowder, black powder in a circle as if a shot has been fired. Bambi, the hunted deer, shot by the hunter.

The book Portraits of a Marriage by the Hungarian author Sandor Marai contains a wonderful scene in which the narrator and protagonist sneaks up to the woman he desires. He approaches her as if she were a prey and, later, reminisces the scene to explore his motifs: ‘It is very possible that at that point I still had the hope, deep, very deep inside my heart, that somewhere in the world there would be a body that could harmonise completely with mine, and with the help of which, I could transform the thirst of desire and the saturation of satisfaction into a mild quiet – corresponding to the dream people call ‘happiness.’ The mistake of this thought was that happiness as such does not exist, but I did not know that by then.’

It basically comes down to the protagonist’s pursuit of ‘happiness’ and whether it exists or not, it is clear that it is a temporary state and not a remaining constant. Happiness is like life, it passes. Love, in all its shapes, demands exactly the opposite: something infinite, forever, like the soft murmur of a PC when we write something. In other words: as long as we live, we have the duty to love. It is because of this that love, seduction, is always paired with desire for death, the fixed stasis of a moment with the wish to efface oneself and to coalesce. The hunt – evidently linked to murder – is a symbol of this desire for the One. The hunted object is, in a sense, always innocent and the hunter appropriates the power to love, to experience total bliss in the ritual: aiming the gun, the silence in the forest, slinking past crackling leaves, a beautiful hit. Finally, a corpse always remains, until the next hunt. Seduction, true seduction, is surely accompanied with play and flirtation, in which all innocence has been put aside and one is no longer a deer, but perhaps a squirrel, cheerfully jumping up and down, ostentatiously, from branch to branch. Or like in New York, the city that Beck comes from, a rat who scrounges around waste bins to find a meal – ‘tailed rats’ is the nickname for rats over there.

Ah, that sweet seduction, the lovely game of flirting. The French painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806) painted many pictures of women in lace dresses making advances on men in wigs. One of them depicts a woman on a swing, below whom is a reclining young gent who can see under her skirts as she lifts her leg and lobs her left shoe to him. The images of this French Rococo Painter who lived at the time of Louis XIV, the Sun King, now seem gaudy to us. The French Revolution forced him to give up his career in painting; he spent his last years doing administrative jobs and finally died in obscurity. His love life I have not studied, but his paintings show the appeal of forbidden, secret pleasures. The ritual of the hunt is also marked by the forbidden, because it is in silence –in secret- that the hunter approaches the prey to avoid being discovered and the bounty escaping. No matter how beautiful or seductive the game might be, the hunt remains a tragic affair. The killing is cold, sometimes repulsive, sometimes necessary. It is always the shot that matters. A hit or not?

Fragonard's The Swing

The famous philosopher Petrarch (1303-1374) wrote the following on love: ‘Despite myself I love, forced by faith to sadness and tears.’ He adds that love is ‘a hell that fools make into their paradise’, a ‘tasty poison’, ‘an attractive torment’, and ‘a death that has the look of life.’ Put differently, pleasure and grief are inextricably interwoven, like Siamese twins.

Petrarch (1304-1374)

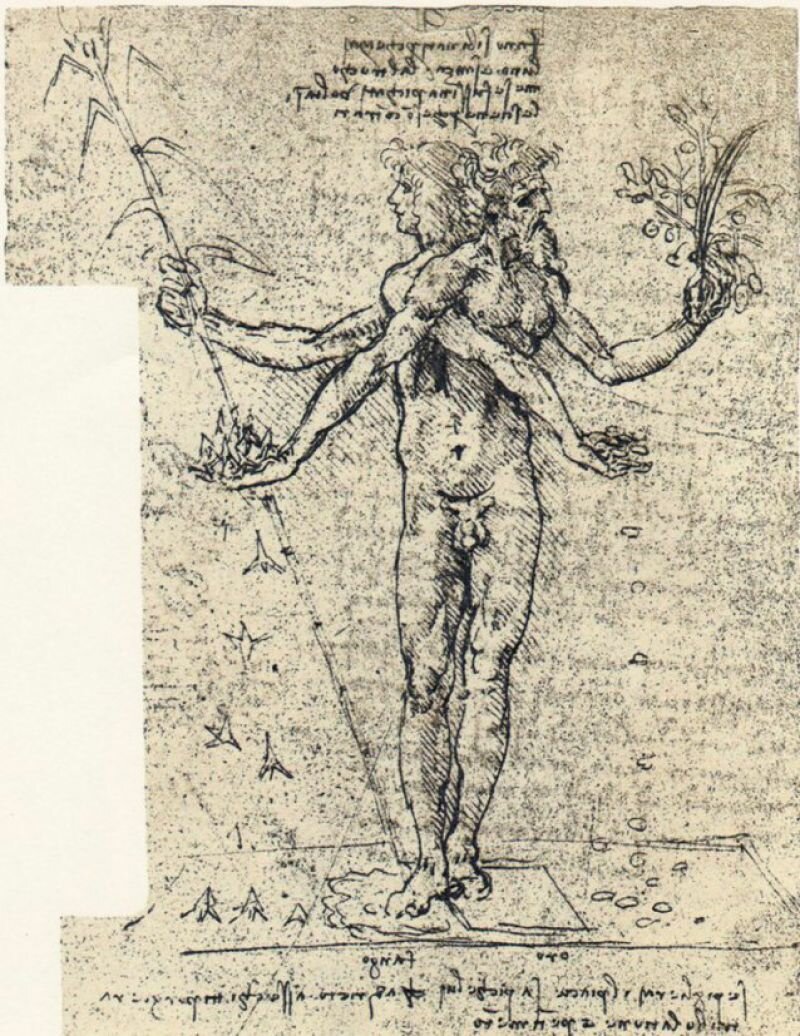

Leonardo da Vinci made an allegorical drawing that shows two men who share torso and legs. They represent Grief and Pleasure. The one man is old and wears a twig from an oak tree, the other is young and has reed in his hand, carelessly dropping some golden coins. Da Vinci provided the following commentary: ‘They are depicted with their backs to each other for they are each other’s opposite, but sprout from the same trunk for they share the same origin. (...) Pleasure has been depicted with some reed in his right hand, insignificant and weak, that can cause nasty wounds.’

Da Vinci's drawing

The pursuit of pleasure or the sublimation of love in the mind by chasing dreams, that is what matters to Da Vinci. The latter is bigger, more intense that physical lust: the dream of the One is linked to wishes and fantasies that always end in grief. Whatever is hunted (a girl, a young boy, an older one) ambivalence always reigns here, as a swing that arouses in us an alternation of fear (this is too high, I might fall) and joy (I’m flying). Up and down, from heaven onto earth – ouch, what a desire.