I recently read a news article critical on the way social media is used by the public after disasters occur. It questioned whether sharing intimate tweets and photos originally posted by victims of a disaster on online social media platforms expresses genuine sympathy or is merely an act of voyeurism.

It was in response to the social media activity following disasters such as the Boston bombings of 2013 or the recent tragedy of flight MH17 in the Ukraine. In both cases graphic and intimate images and messages regarding victims emerged online and were shared en masse by the public without any accountability. Although the article's main question seems to describe an activity that can be justifiably criticized, the piece ended with a disappointing conclusion, stating: “the line between sympathy and voyeurism appears to be wafer thin.”

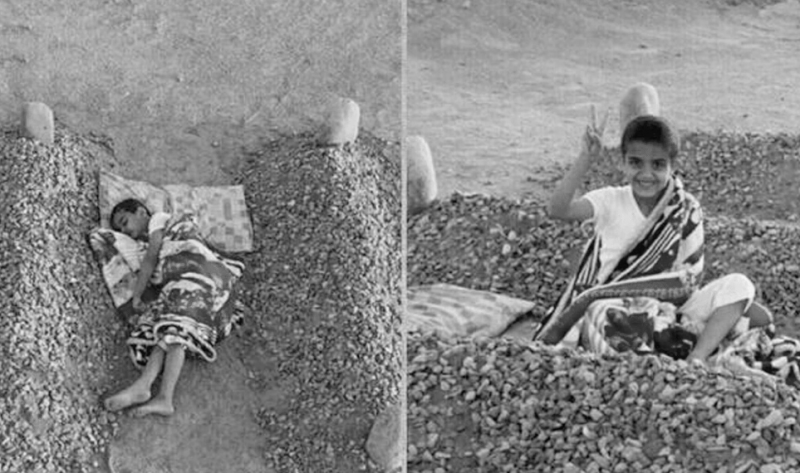

The problem with openly sharing photos, information, assumptions, etcetera on social media platforms isn’t necessarily that others will turn out to be misinformed – although this is still a legitimate point to make. Arguably, sharing the photo of a ‘Syrian boy’ in between his ‘dead parents’ as an illustration of the horrors resulting from the civil battle in Syria could have had a benefit. Though erroneous, when that image spread it got a reaction from the West that no longer could ignore the atrocities in Syria. The fact that the boy in question was neither Syrian nor actually orphaned (it was a Saudi boy posing for a photograph by Abdul Aziz al Otaibi) didn’t take away the fact that many Syrian children are suffering. What does this newly found awareness from Western citizens really mean? It doesn’t mean anything to the Syrians - the conflict is still raging - so does it mean anything to us?

This brings me to a different side of the story; the moment that the West is hit by catastophe. After the disastrous turn of events surrounding Malaysia Air flight MH17, social media outlets flooded with horrific images of clothing, airplane parts, and bodies strewn across a flowery field. Images of the contents of ripped open luggage. Images of stuffed animals. It appears that disasters do have the effect of luring many into the realm of voyeurism. This voyeurism isn’t a pleasurable gaze into the private space of another, but its fantasmatic, internalized counterpart.

I would like to argue that so many of us in the West live in relative safety, freedom, and prosperity that it becomes increasingly difficult to identify with people affected by disasters and suffering around the world. Let me take the example of stories of monsters told to children. The older children or adults tell stories of monsters and ghosts coming to haunt you in the night. As the stories pile up you have yet to encounter your first sighting. One evening you are in bed and the pile of clothes on the chair in your room appears as a silhouette of the monster you have created in your mind. This is the type of fantasy at play. Not a yearning for the monster to be real but knowing that it, in a sense, is real without knowing what it looks like and having the need to define the monster. Seeing the monster, acknowledging it, in this way becomes a subversive duty defying the reality that there is no monster for you to see.

Sharing graphic images and messages online can express a genuine (but perhaps misplaced) feeling of sympathy. However, more likely they express a need to free oneself from the burden of living in safety and not having a real idea of what disaster and collective suffering really are. We constantly hear ghost stories so our duty becomes to seek out what our nightmares look like. In order to try and grasp the feelings of those affected by the tragedy, onlookers share intimate tweets from victims, photos of the disaster area, speculate about culprits, etc.

This digging into the world around a disaster happens immediately after the first glimmers of the news are out there. The online presence of victims or possible culprits is excavated and spread (note the circulation of false accusations directed at innocent people regarding the Boston bombings). But all of this happens in the name of sympathy for those affected. In this way the wafer thin line between sympathy and voyeurism doesn’t need to exist; sympathy requires voyeurism.

Let’s be clear; this is not a polemic engaged in a struggle to dismiss genuine grief. It is to try and show the duality in trying to remedy those suffering by freely spreading images and accounts of suffering. The harmful aspect is that this act of sharing replaces the moment of reflection immediately with a moment of activity, or rather pseudo-activity, an act that merely serves the status quo, or as Theodor Adorno put it: (..) Pseudo-activity; action that overdoes and aggravates itself for the sake of its own publicity, without admitting to itself to what extent it serves as a substitute satisfaction, elevating itself into an end in itself.

The act of sharing horrific images means, “look at these atrocities! Share if you care! I care!” Implicitly leaving anybody who doesn’t share as though they don’t care. This is the pseudo-activity within burden of collective suffering; the act overdoes itself and aggravates its intention (that of offering support to victims and affected families by ‘raising awareness’). It doesn’t show support to grieving families of victims but a need to partake in their suffering – sympathy comes from the Greek words syn meaning “together” and pathos meaning “feeling”, and pity derives from piety, which comes from the Latin pietas meaning “dutifulness.”

The burden of our position of relative safety in comparison to those in grief requires us to define suffering the moment we encounter it. This implicitly makes collective suffering a duty. However, to “feel together” becomes an impossibility almost if you are not directly affected by such a tragedy. There is no line between voyeurism and sympathy. The latter depends on the former. Perhaps instead of relentlessly confirming and repeating the stories of monsters one should silently provide a flashlight for those hiding under duvet, petrified for what might happen during the night.