Hanae Wilke (1985, NL) is an artist and writer living and working in The Hague and London.

1000 Things is a subjective encyclopedia of inspirational ideas, things, people, and events.

Read the most recent articles, or mail the to contribute.

Hanae Wilke (1985, NL) is an artist and writer living and working in The Hague and London.

Directives, or instructions, are given to the voluntary Mass Observers to report on specific matters like conversations overheard in the pub, what one saw on their daily route to work, the steps in their housekeeping routine, the contents of their mantelpiece:

Write down in order from left to right, all the objects on your mantelpiece, mentioning what is in the middle. Then make further lists of mantelpieces in other people’s houses, giving details of the people themselves whether they are old, middle aged, or young. Whether they are well off or otherwise. What class, roughly, they belong to. Send these lists in. If possible, also take photographs of mantelpieces.

.

The Back Garden

This is the area directly outside the kitchen and dining room windows. The patio area is done with crazy paving and there are flower beds round these sides with bushes and a Buddhleia tree climbing the fence side at the left side of this photograph. This photograph shows the corner area underneath the dining room window where the cat likes to sit out during the warm weather – you can just see its black shape at the back.

Others kept diaries that detailed their ordinary and often entirely uneventful existence:

19.11.81

Dear Sir,

Since writing to you last year, yet another high street shop has closed. These strangely enough have all been ladies dress shops. The first one closed in August and was destined to become yet another Building Society. However, the council sensibly stopped that happening, since the High Street already has four. At the moment, this shop is being used as an Oxfam store and people are obliging dump all the their “jumble sale”…

The documentation of a day's house work:

A detailed drawing of one’s living room:

And written descriptions, too:

Through this collective social project, the Mass Observation team has created an immense archive of the ordinary, the boring, and the mundane through which a nation is chronicled.

I’ll never see the elderly gentleman’s collection for myself. A few years ago, he threw out his entire archive when he convinced his wife that they should move from their beloved home into an overpriced apartment on the third floor. He’s miserable in that boxy apartment and longs for the flowering green gardens of the old house. But the apartment was bought for more than it was worth and he has no choice but to stay put and sit out his old age.

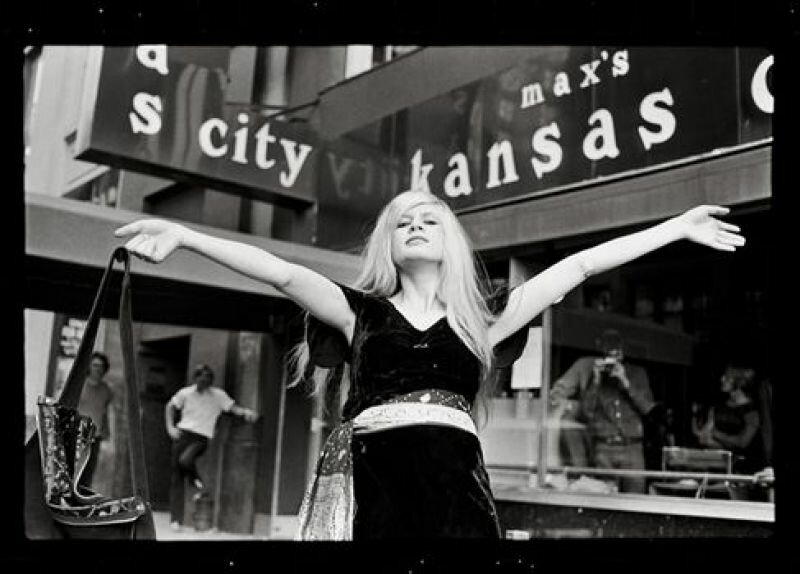

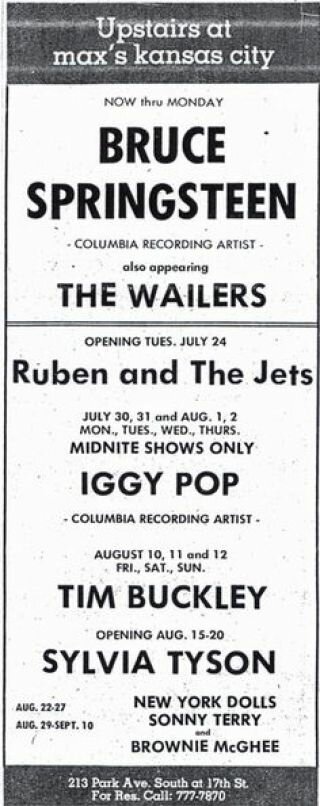

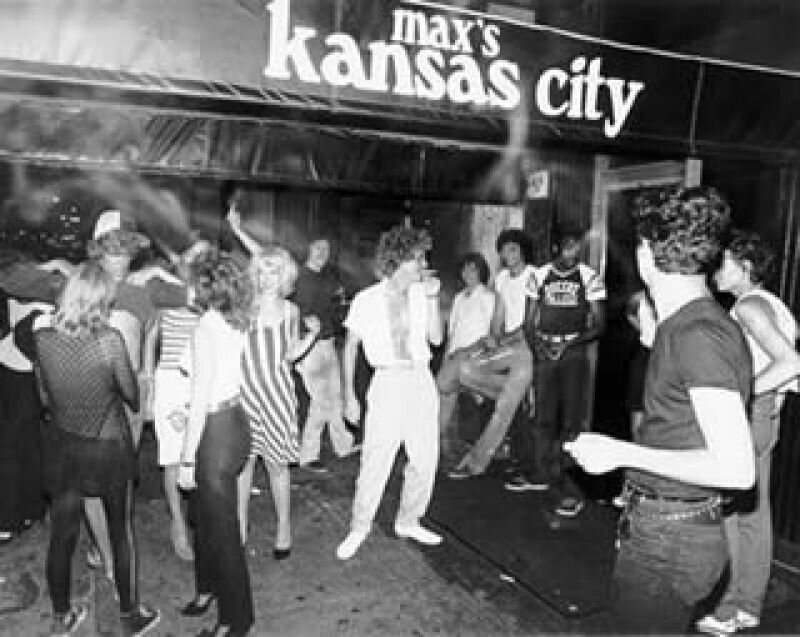

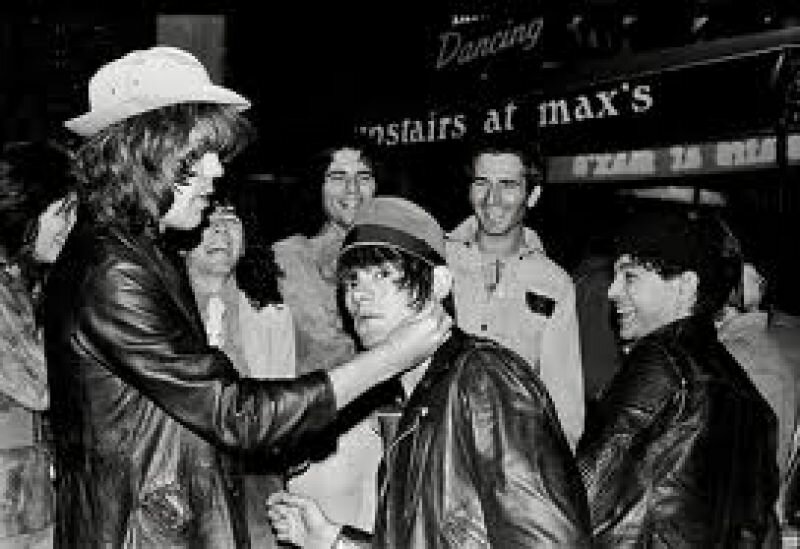

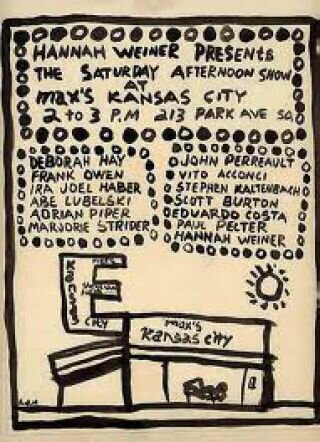

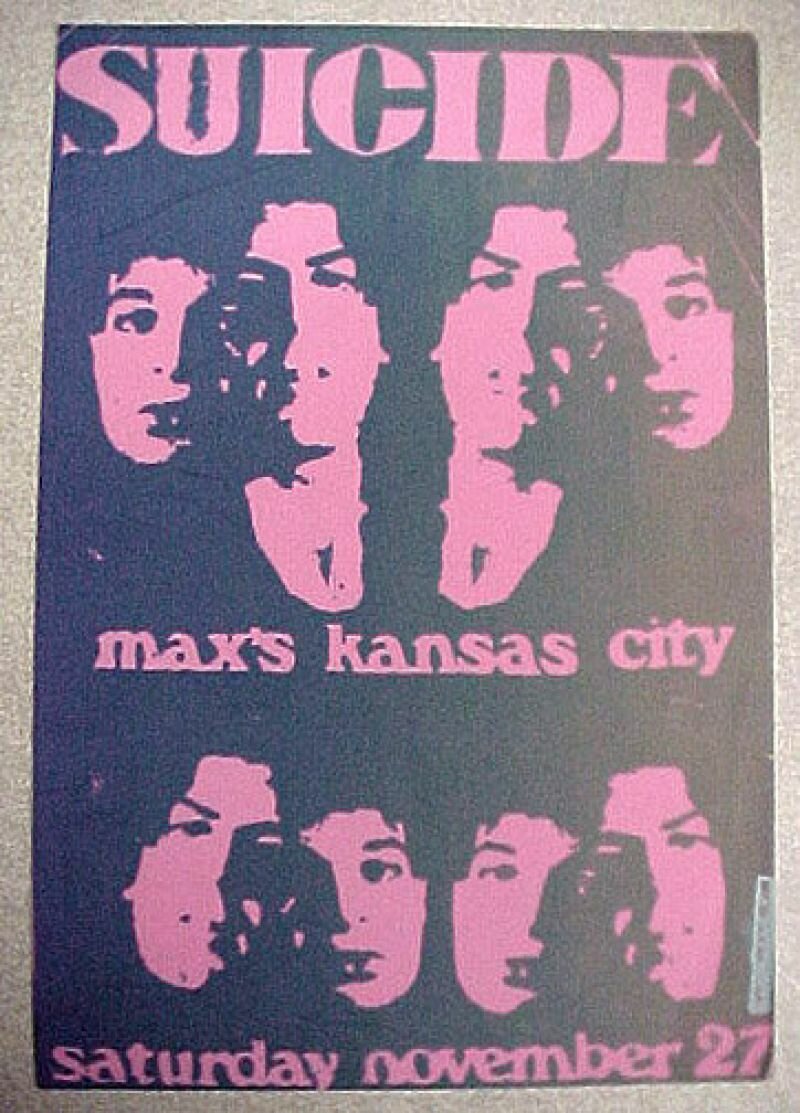

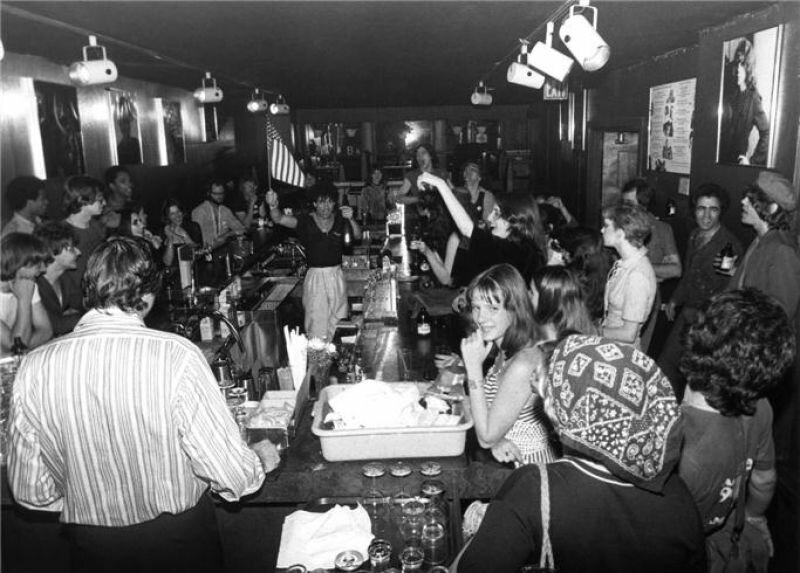

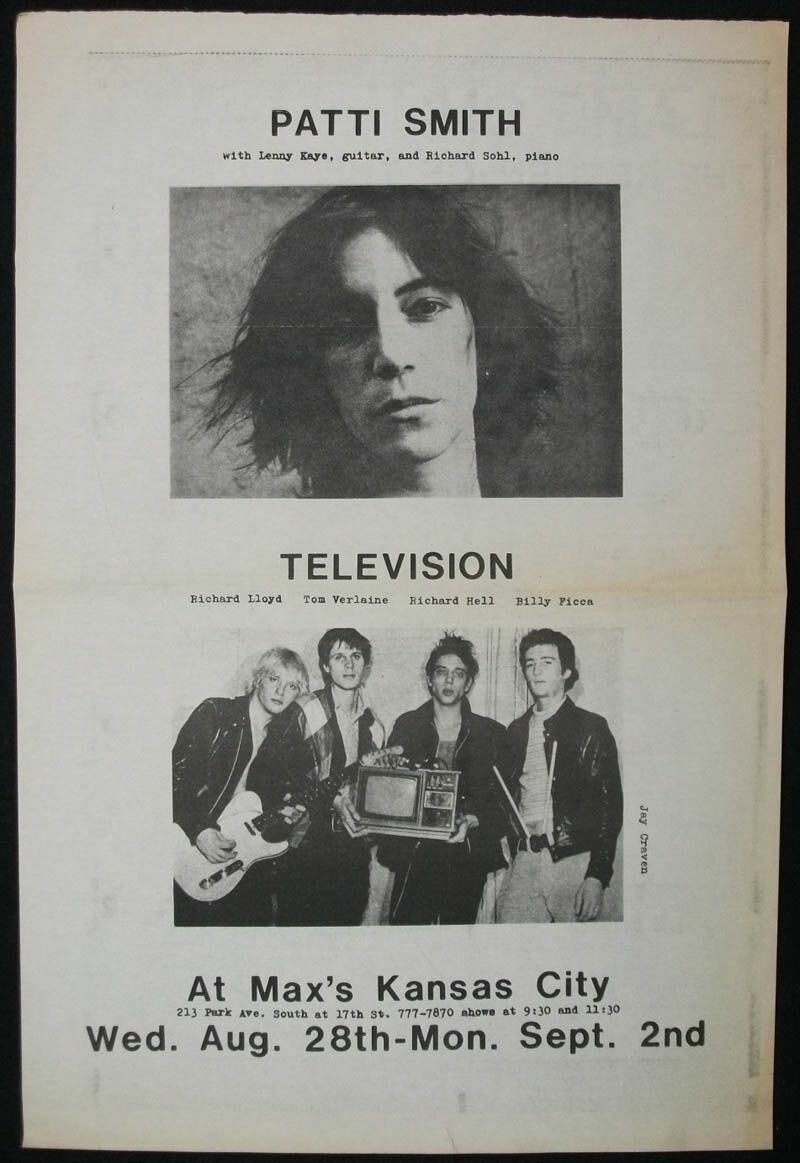

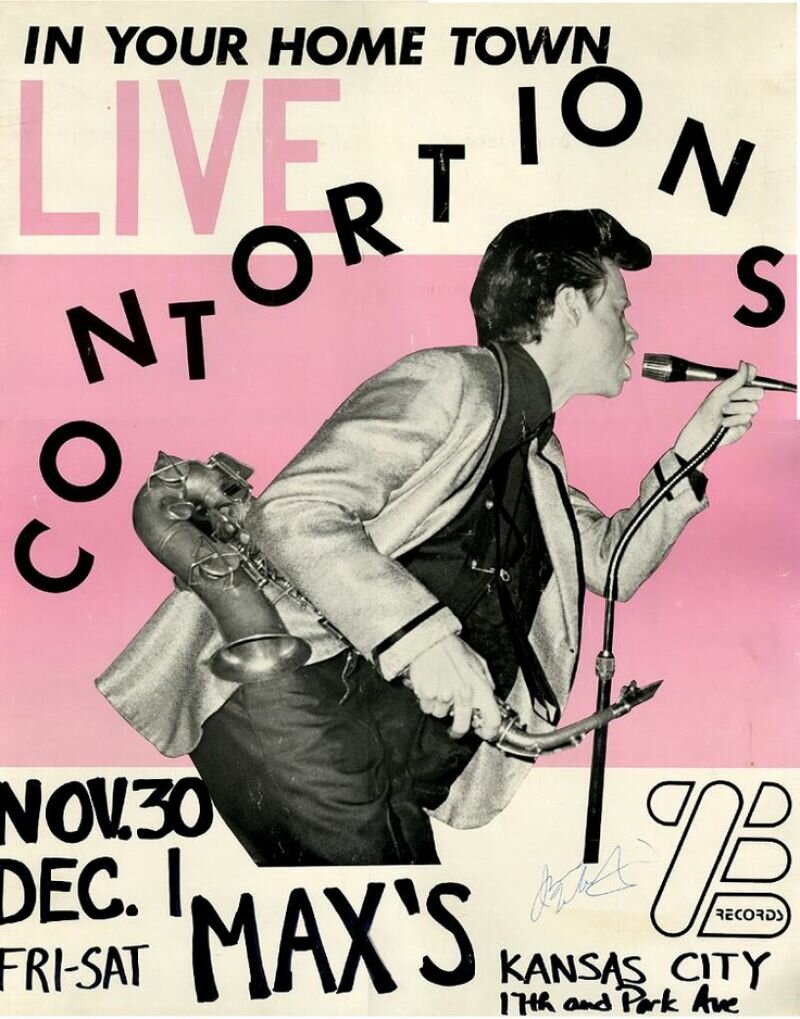

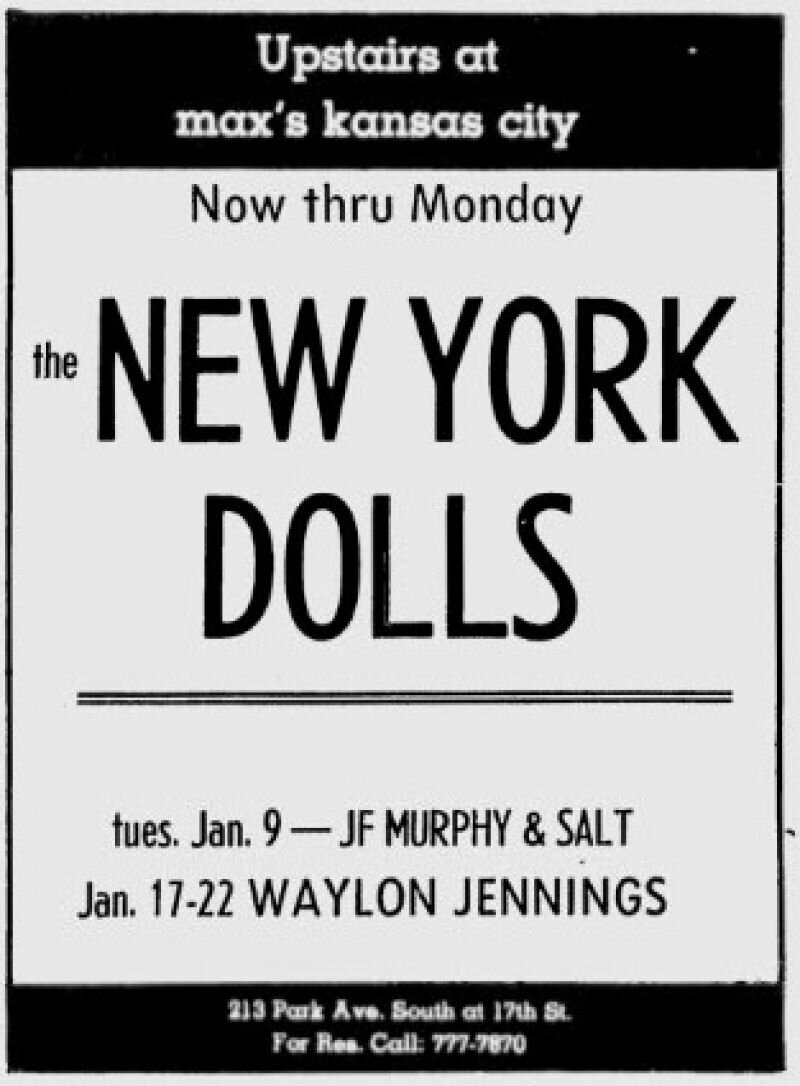

I met an art critic, a man well into his seventies, who told me of New York in the late sixties and of Max’s Kansas City: an unreal sort of meeting place where you could glance over the Velvets, William S. Burroughs, Stanley Kubrick, Janis Joplin, Dan Flavin, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, Dennis Hopper… the list is mind boggling and seemingly endless.

Critical art writers typically deal with resistance along the way and this critic, too, at times met with the steely glances of slightly scorned artists. But walking into the bar with the bulky Robert Smithson would make him feel a little bit safer from the evil eyes cast by the glamorous Warholians at the back, and from the sneers thrown his way by the Abstract Expressionists between their heavy discussions.

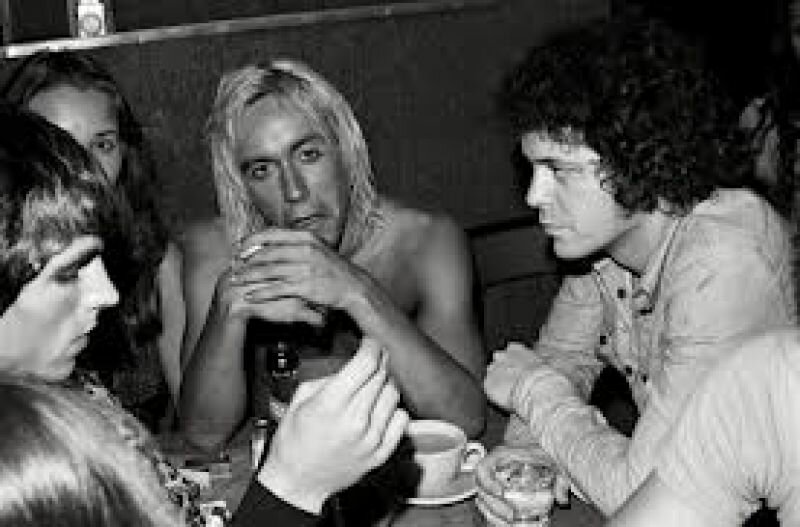

"I met Iggy Pop at Max's Kansas City in 1970 or 1971," recalled David Bowie. "Me, Iggy and Lou Reed at one table with absolutely nothing to say to each other, just looking at each other's eye makeup."

Myra Friedman, visitor to the bar explains:

Max's was a lot more than a magnet for sex, games, and drugs. It was an earthy, invigorating hangout, and the people who Mickey let stay there for hours and hours were definitely a breed apart, when being "apart" had real meaning in the world. I remember it for lots of conversation with lots of people who had lots and lots to say, and looking back on it now, the hum of the place strikes me as sort of the last hurrah of a genuine American bohemia. Like a great piece of writing, it was airborne from the minute it opened. It had beautiful wings; it soared.

It won’t come as a surprise that many of Max’s visitors had trouble paying their tabs. And in the typical artist’s tradition, they often paid their debts with artworks. Mickey was so eager to surround himself with artists, musicians, and writers, that he would allow them to spend thousands of dollars worth of food and drinks. A few beers in exchange for a Carl Andre? Doesn’t sound like a bad deal at all for Mickey.

Going abroad is full of new encounters, customs, and traditions. One unavoidable encounter with the unknown resides in the bathroom: the foreign toilet. Anyone who’s ever been to Japan, for example, will immediately understand how heeding the call of nature can turn into an adventure. There, the more upscale toilets are entirely automated, with the luxury models offering more features.

The simplest versions include a jet stream of water pointed towards your nether regions (strength and aim adjustable) and a drying function to finish off the job. In the more advanced models, you’ll find a button that imitates the sound of a toilet flushing, the solution to the excess of water wasted because the Japanese kept flushing to mask the sounds of bodily functions. The strangest of the Japanese electric toilets I encountered included a remote control. I’m still not entirely sure in what situation you would find it necessary to entrust the power to spray and blow dry your privates to another person standing metres away.

Slavoj Zizek finds his own examples of the cultural codes inherent within an object as banal and mundane as the porcelain throne:

In a traditional German toilet, the hole in which shit disappears after we flush water is way up front, so that shit is first laid out for us to sniff at and inspect for any illness; in the typical French toilet the hole is far to the back, so that shit may disappear as soon as possible; finally, the American toilet presents a kind of synthesis, a mediation between these two opposed poles – the toilet basin is full of water, so that the shit floats in it, visible, but not to be inspected. No wonder that, in the famous discussion of different European toilets at the beginning of her half-forgotten Fear of Flying, Erica Jong mockingly claims that ‘German toilets are really the key to the horrors of the Third Reich. People who can build toilets like this are capable of anything.’ It is clear that none of these versions can be accounted for in purely utilitarian terms: a certain ideological perception of how the subject should relate to the clearly unpleasant excrement that comes from within our body is clearly discernable in it.

Zizek, Slavoj. How to Read Lacan. London: Granta Books, 2006

I cross the Thames; silver under a grey sky, and watch the throngs of pedestrians pass the bridge and make their way to the museum. There’s something magical to being one of the newest additions to this city, feeling myself immersed in a great crowd with the realisation that this is home now. Here, solitude lends itself to becoming a welcome spectator seat.

As Tate Modern comes into view, I’m surprised to see a group of large, furry animals standing in front of the museum. There must be at least fifteen of them, donned in intricately detailed costumes of cartoon versions of cats, bears, foxes, and wolves. These are not your run-of-the-mill dress up shop costumes, their muscles are defined, sturdy, their masks are eerily realistic, and their jaws open and close at will. I watch as they interact with the spectators, and see the timber wolf taking on his role as the alpha dog, bending his knees and flexing his arms as the tourists snap away. On the other side of the crowd, the silver fox with her big blue eyes walks demurely, somewhat timidly past, and leans her head against the onlookers, allowing them to stroke her, pet her nose, and bury their faces into her furry shoulder.

Outside of the city centre, where the gaping maw of the crater left by the NATO bombings in 1999 still stands as the lugubrious testimony to a bygone time, and past the endless grey concrete housing blocks that sprawl exponentially across the outskirts of Belgrade, there you’ll find an innocuous market selling wares made in China, cheap plastic clothing, and all else one would expect from a market of the sort.

Remnants of the 1999 NATO bombing in Belgrade's city centre.

Serbians in dire need of their BILLYS, POANGS, and EKTORPS flock to the little market stall where they place their order with the staff who drive to the IKEA, five hours away, in Hungary. Obviously, a surcharge applies. This stall is not alone. In fact, many Serbian companies capitalise on this need for IKEA; epitome of a globalised, standardised world of interiors.