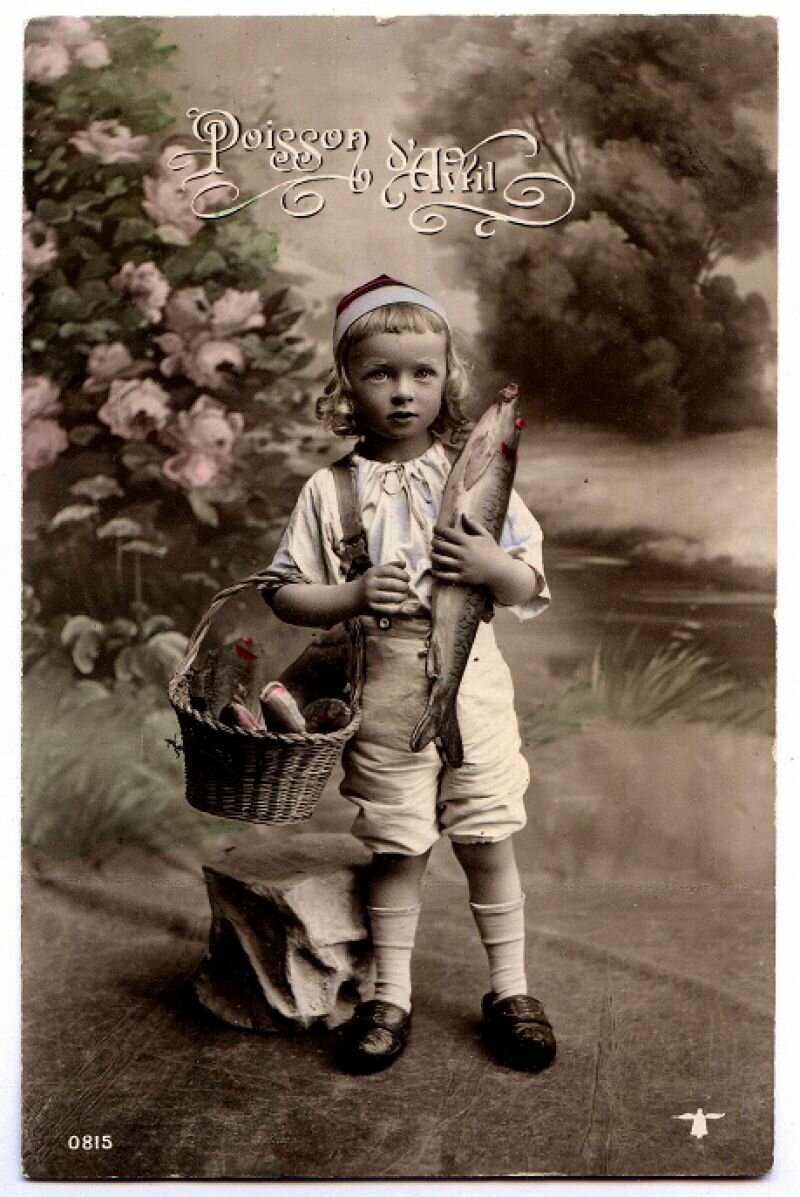

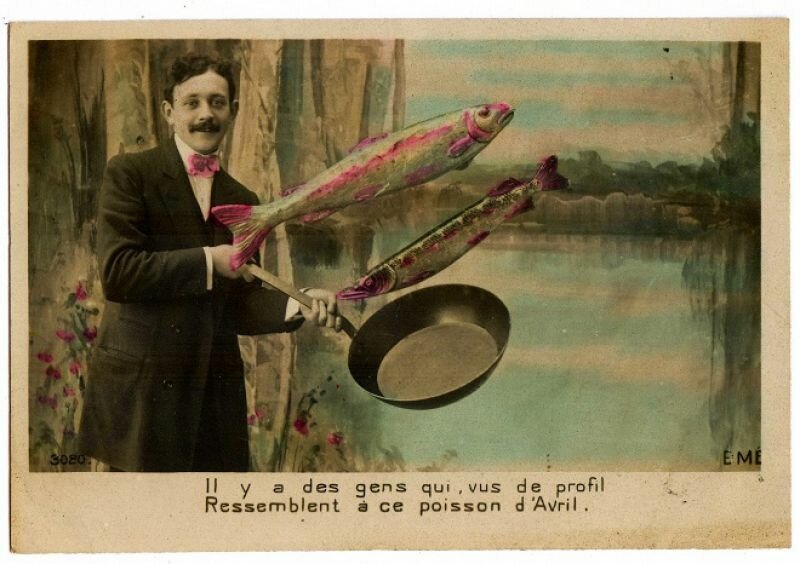

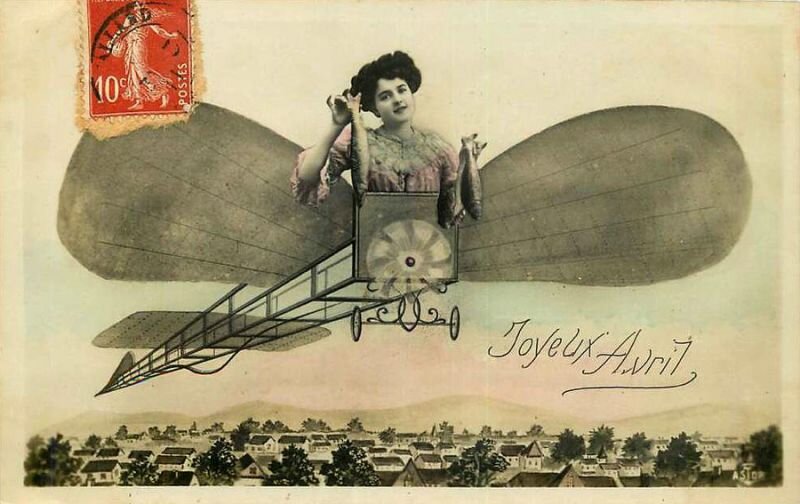

Since the start of the last century, the French have known a tradition of sending one another so-called ‘poisson d’Avril’ (April Fish) messages. These are richly decorated postcards depicting a fish, often surrounded by flowers and a few lines of text.

The flowers most likely allude to the changing of seasons; after all, the 1st of April is set at the very beginning of springtime. More importantly, the vernal equinox is the ultimate metaphor for the blossoming of new love and the excitement that spring brings with it. The fish represents the hope of love requited by a (secret) object of affection, captioned by texts such as ‘Quand arrive avril, tous les fleurs en France, s’ouvrent à l’amour, pêcheur d’espérance!’ (All the flowers in France open in April for love, the fisher of hope!)

The sender hopes with all his heart that the addressee will answer his love: ‘Parce message discret / je vous envoie, ma toute belle / Mon plus cher et plus doux sécret / Mais vous ne serez pas cruelle?’ (With this secret message I send to you, my beautiful, my most precious and tender of secrets/ Please, do not be cruel.)

From the beginning of 1900, tens of thousands of April fish swam their way to an equal amount of lovers, proving to be the way to declare your love, albeit anonymously, in the form of what essentially is a Valentine’s card avant la letter.

It’s not quite clear why a fish was chosen as the symbol of springtime and love. Some believe that it has to do with the mating season of the fish, which occurs around April. During this period a fishing ban is enforced in France. To mislead illegal fishing, fake fish are thrown into the water during mating season. When a fisherman catches a pseudo-fish, men cry ‘poisson d’Avril!’ The April Fish is like the French April fool’s gag.

In this sense, the tradition of the April Fish is still alive and kicking. On the 1st of April, cut out paper fish are stuck on the back of an unsuspecting passerby who, when the fish on his back is noticed, is declared the ‘poisson d’Avril!’

Besides paper fish, edible fish are also popular. Around the 1st of April, the storefronts ofFrench patisseries and chocolatiers display an unending supply of chocolate fish and all sorts of fish-shaped pastries. Still, the fish is an object of seduction, although no longer through the mailman’s delivery, being instead served on platters in shop windows. Because in the end, the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach.