On my way to Italy last summer, I had to think continuously about the Stendhal-syndrome, which was recently identified by the Florentinian psychiatrist, Prof. Dr. Graziella Magherini, in about a hundred people. These people had gone mad after an overwhelming experience of art, as had once happened to Stendhal. After a visit to Florence the French writer described how the divine beauty of the city caused him severe palpitations, and a fear of collapsing with each step he took. In reality, of course Stendhal retained his self-control, which distinguishes him from the patients of Prof Magherini, who were each and every one ripe for the institution.

The longer I thought about it, the better I understood that Stendhal did not lose his mind under the influence of that experience of beauty, but wanted to. What could be, in his time, a more elegant proof of human refinement and sensibility than to faint in the face of a work of art? The nineteenth century had barely began, the psychiatry was yet to be invented and it was still in vogue to take pride in one’s psychosomatic afflictions.

Why all this came to mind on the way to Italy I do not know, but in each case, it wasn’t because I was underway to whichever Italian art attraction. On the contrary, my aim was isolation, the peace to read for a couple of weeks without being disturbed.

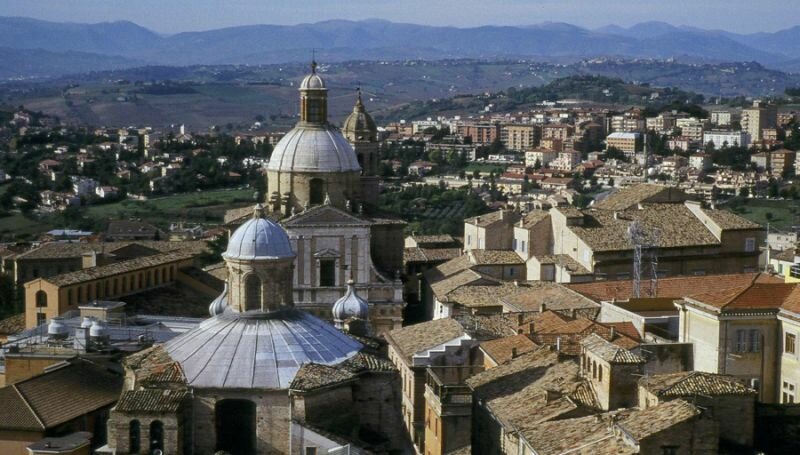

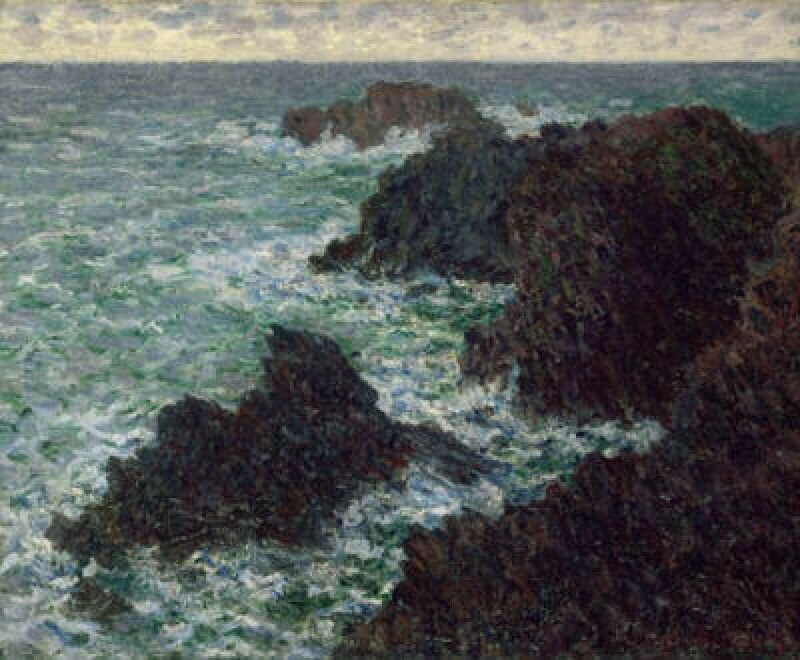

I lodged in a cottage near the city Macerata, in the province of Marche. The cottage offered a view on a valley, which could effortlessly compete with the most beautiful landscape paintings in the world. I installed a long chair on the roofed porch, sat down and started reading. Motionless I sat in my chair for days, enjoying the world, as I enjoyed being in the shade of the sun. I forgot time and thought everything would stay like that forever.

I read gripping Italian fiction by the likes of Luigi Pirandello, Cesare Pavese and Claudio Magris, as well as an in-depth study of the life of Francis of Assisi by the Dutch Helene Nolthenius. But I was most taken by the autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, the brawler, vain as noone else, the great mind with the short temper, who did not recoil from retaliating for the slightest mockery with premeditated murder.

Such a contagious character! The sixteenth-century goldsmith and sculptor demonstrates the art of lying as no other. After every page of his autobiography I understood better how to narrate: some true occurrences are to be related in detail, and additional verisimilitude is provided by adding some untruths.

I was about halfway in Cellini’s life story when I experienced a reader’s block. My uninterrupted sitting had made my body stiff as a board and it longed, incited as it was by Cellini’s continuous boasting of his physical courage and energy, for movement. The moment I laid down the book my hero had just been thrown in jail by the Pope. ‘He will stay there for a while,’ I decided, ‘it’s about time to immerse myself in Italian life. To Macerata!’

In Macerata, there appeared to be an open-air theatre where Carmen was performed that same night, the opera by Bizet. There was still space among the gods, a high-up room with an open wall. There were six seats for me alone.

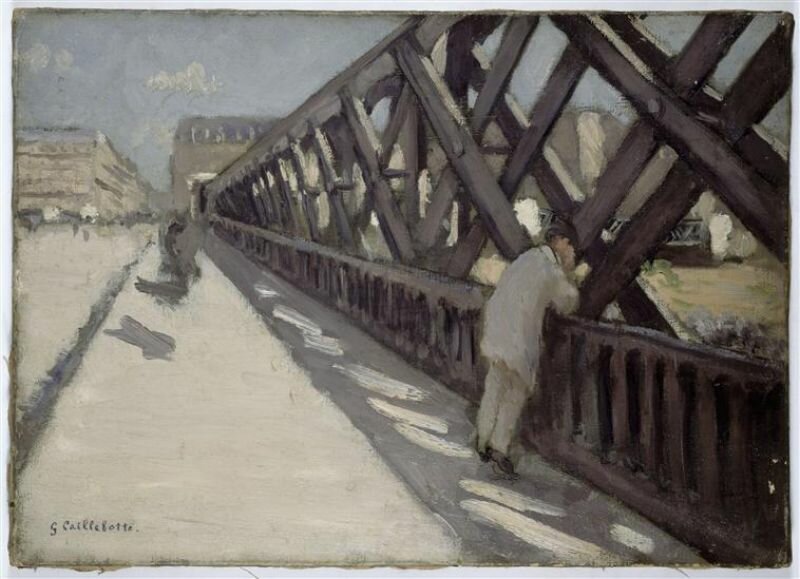

The directors and designers of the spectacle managed to almost completely erase the 120 years the world has been revolving since Bizet's death. Everything was of a nineteenth-century authenticity. Real horses appeared on stage as well as real tilt-cars, and there burned real fires. The populace was portrayed by a mighty throng of real lower-class people, as have not been painted in the 120 years since Gustave Courbet. There was also a real cricket in the orchestra pit, which gave off a real rural atmosphere, especially during the campfire scenes. But the most real of all was the bat that lived in a crack in the wall of my little arcade.

During the whole performance it flew on and off, shy and beckoning at the same time. It was pitch-dark up there and my already increasing melancholia threatened to deteriorate into a genuinely grave gloom. That became too much for me, and so I tried to combat the pestering bat, with my rolled-up programme for a sable. I hit and stabbed, mowed and slapped. But when, during a slaloming movement between my six chairs, I lost my shoe, which I could barely save from falling down to the hall below, I began to recognise the slapstick character of the situation. I refrained from further battle and, a few minutes later, I was sitting on a terrace on the opera square with relief. After some Sambucas, I was fully back in the now.

The next day I awoke with a swollen right foot. It hurt, but enjoyed being bound to my cottage, my terrace, my valley and my books. I limped to my lying chair, dropped myself in it and, as if I were the jailer myself, opened Cellini's book to see how our prisoner was doing.

I could not believe my eyes. Not the fact that he escaped surprised me, but how. Especially two details in the description of his flight brought my heart to a standstill.

Cellini is imprisoned in a castle led by an amiable and intelligent chatelain, Messer Giorgio. The two get along fine and lead wonderful dialogues. It turns out that the chatelain has the bad luck to entirely lose his wits every two weeks. The one year he thinks he is a frog, the next that he is a cruet. Shortly before Cellini's breakout it starts again: this year, Messer Giorgio has made up his mind, he will be a bat!

I broke out in sweat, but by itself I could have still borne the bat, if it would have stayed at that. The worst, however, was still to come.

Some pages later, the escaping Cellini meets with an unexpected setback: the chatelain appears to have built two extra walls around the castle. This provides yet another chance for Cellini to display his heroism, because of course, after a daring feat of clambering, he stands outside. On this very moment (and only then, as if he had held it in) he loses consciousness. When he wakes up he feels a bone fracture, 'about eight centimetres above the right heel.'

I swallowed, looked at the ridiculous swelling in my right heel, slammed the book shut and hurled it into the valley as far as I could.

For three days I struggled with ice cubes wrapped in dish towels, and peered at the landscape. Then I could walk again.

In a neighbouring village I found the house of Dr. Italo Seminterrati, doctor and psychiatrist. He opened the door himself and welcomed me while whistling, as if he had been waiting for a patient for weeks. In his consultancy room he offered me ice tea with honey, which was brought in by a maid in a nineteenth-century nurse outfit. Then I had to tell my story.

I told him everything as precisely as I could. Eventually the doctor said: 'You are undoubtedly sensitive to symbols and there's nothing wrong with that. But Italy is teeming with bats, just like 500 years ago. That you have encountered one on paper as well as one in real life, shortly after each other, does not immediately strike me as a miracle.’

‘That has nothing to do with it, I did not feel the least bit of pain that evening! Do you really disbelieve that this can be a case of vehemens imaginatio, the intensified imagination that, amongst others, your compatriot the Holy Francis suffered from? He awoke one day to suddenly have these crucifixion wounds, and not just on one foot!’

‘That’s what I meant exactly,’ the doctor laughed, ‘the Holy Francis did not have any shoes!’

Then Dr. Seminterrati stood up and said: ‘Sir, I believe you are completely healthy.’ He shook my hand in a friendly manner, accompanied me to the door and wished me a good time for the rest of my holiday. ‘Go see some art,’ he added, ‘it will do you good.’

http://www.cornelbierens.nl/