21.11.2013

08.10.2013

I have an early childhood memory of receiving a postcard from my neighbours who were on vacation in Limburg. On the left part of the card “KR Brinkman Fam.” was written. I wondered with surprise why they’d only leave an abbreviation when there was still so much white space left on the card. Despite that enormous vaccuum, I remember my mother being very pleased with this postal greeting.

This is the essence of a postcard; it’s a gesture of presence. The postcard can contain a message that's nearly empty, that does little more than communicate the sender’s message: “I’m here” or “I’m thinking of you”.

Since college, I’ve been steadily building my collection of postcards. All in all, I have around three shoeboxes full of them. There’s no real underlying theme. There are the prototypical “happy birthday” cards. On one of these cards, meant for a man’s birthday, is printed a shaving brush, a beer jug, cigars, a miniature car, and a slightly pathetic bouquet. One birthday card for a woman shows a cyclamen, a mixer, a candleholder, a sewing machine, and other assorted household appliances. These are still lifes from the fifties that are becoming increasingly rare.

I have Turkish and Italian cards, countless art cards from the Kröller-Müller, the Prado, and other museums. Since 1993, “Free Boomerang cards” came out on the market. These cards were freely available to be plucked from display stands at cafes. There are some very strong ones among these. For example, one printed with the expression “In a dip?” shows a depressed teenager on a white folding chair in his empty study room. Or a card with a man falling from the skies with the words, “Ever considered aerotherapy?” Boomerang seemed to have a card designed for every idea or mood.

I often look through a pile of cards if I want to change my mood or my mode of thinking. My unwritten postcards are not addressed to anyone, and don’t need to ever be sent to anyone. They are images and ideas in their own right.

The philosopher Jacques Derrida takes this a step further in his book, La Carte Postale: De Socrate à Freud et au-delà [1]. In the Bodleian library in Oxford, he found a postcard on which Plato and Socrates are depicted. This card fascinated him, because neither the meaning of the card, the image, nor the text on the back correspond to its message. It is a gesture, an impulse, a transmission, or “un envoi,” in French. It takes flight and in that, finds its power. Every letter has certain content; the postcard has no need for that.

Derrida claims that a philosophical text is like a postcard. Plato’s dialogues, in which Socrates is always the main character, are some of the most well known texts in the history of philosophy. According to Derrida, they can be seen as a series of postcards that have been sent into history. Derrida wonders how Freud received Plato’s postcards 2500 years later.

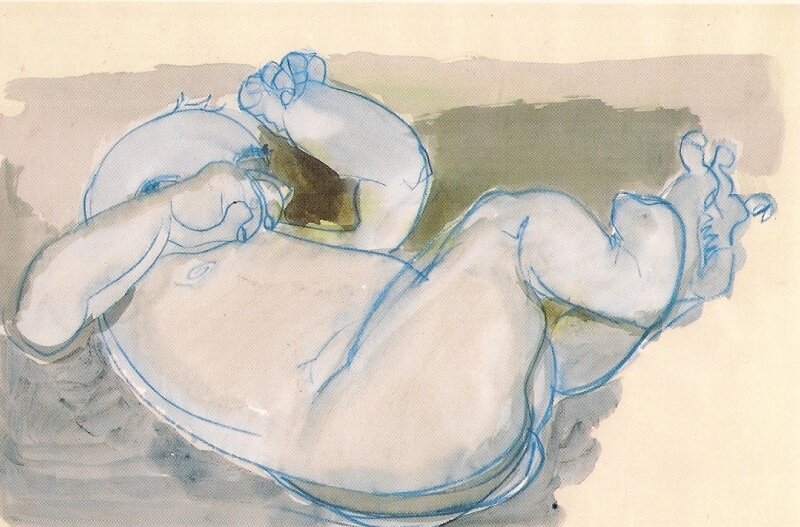

There are certain postcards that I would never do away with. An aquarelle in card form by Marlene Dumas from 1989 titled, “On his back”, for example. I bought this card after seeing Dumas’ exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris at the end of 2001. Each time I looked at it, I became calm, as though my son, one year old at the time, was depicted on the card. I’ll always cherish this card for the therapeutic value it had for me.

Choosing a Dumas-in-card-form is no coincidence: she has often told that her work is often based on photographs and images. She sees the interpretion of images towards an intrinsic meaning as a process in which the different elements overlap.

To observe and to give meaning; we cannot help but bring what we see into words. Dumas puts this very succinctly in an interview: “words and images drink from the same cup, and our ears are next to our eyes”. [2]

Apparently, the poet Rutger Kopland has a huge collection of postcards. Among his writings, there are various poems dedicated to musing upon these cards.This one is titled “Choosing a postcard”. [3]:

Choosing a postcard

On the postcard there are a couple of men

playing pétanque below a plane-tree

at their feet the balls they’ve thrown

they’ve stopped the game and ponder

they are standing in a circle, heads bowed

over what is lying there

there’s a problem lying there

never have their balls lain like this

I could keep looking at this card

it’s probably almost night there now, the shadows

have lengthened, the end of a hot day

and while nothing moves there

invisibly slowly a question is growing

the question: what now

I’d really like to send you this card

© Rutger Kopland

© Tranlation: Willem Groenewegen http://www.decontrabas.com/de_contrabas/2009/08/rutger-kopland-75.html

08.10.2013

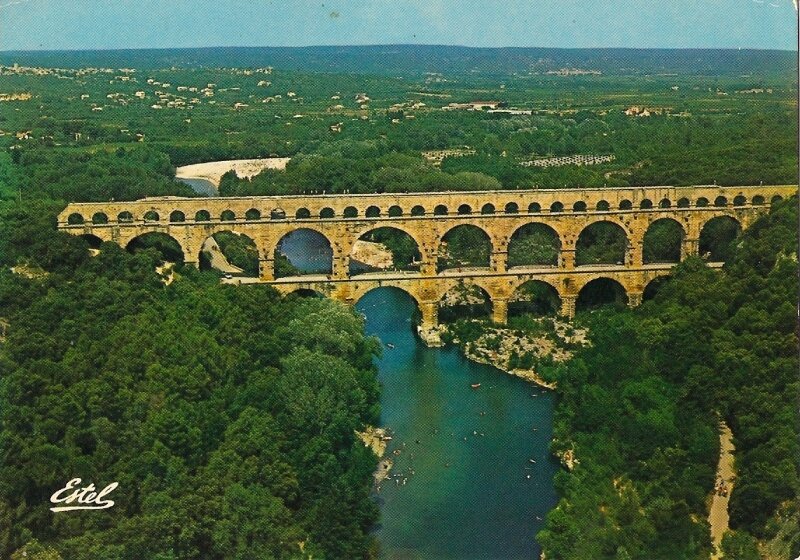

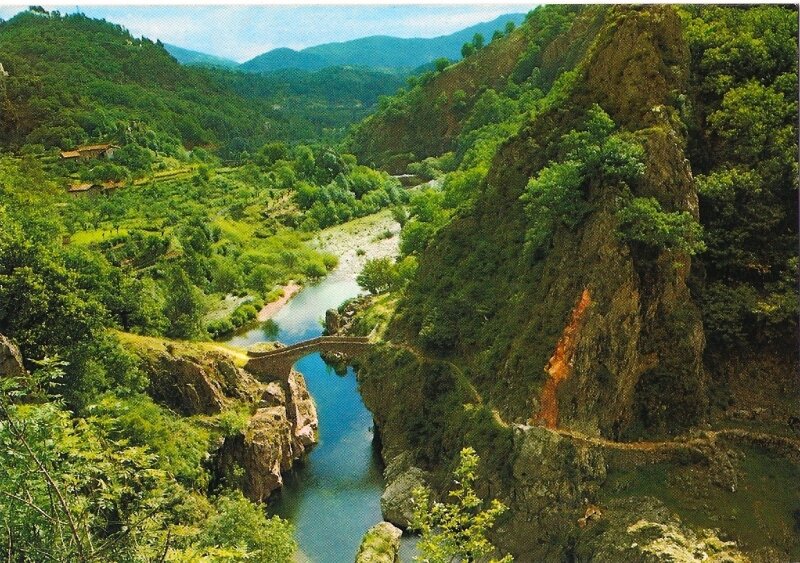

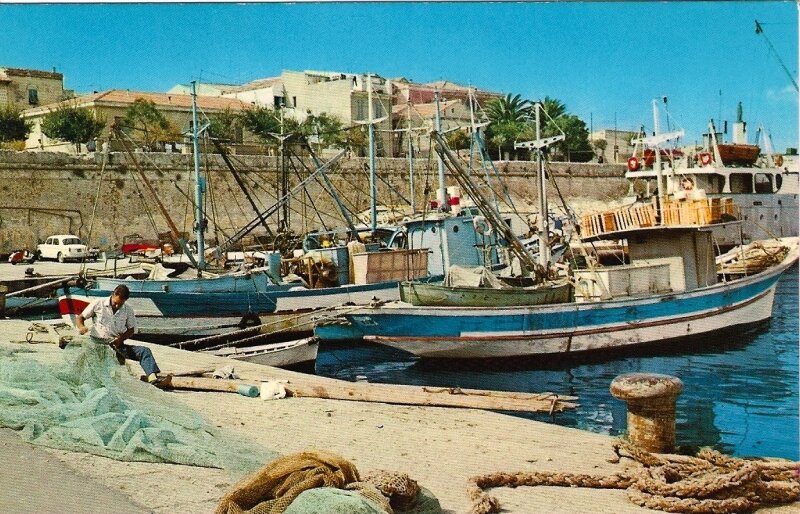

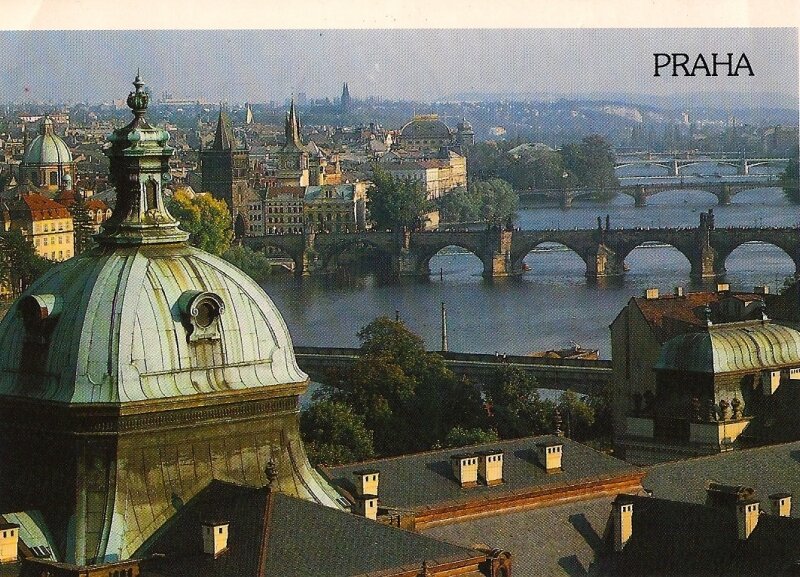

The Grand Tour, a journey to discover the classics, the arts, and social conduct, was exceptionally popular with the British upper class. When in the 18th century, Oxford and Cambridge lost much of their esteem many aristocrats decided to send their post-Eton sons off to explore the world instead. Their accrued knowledge and life experience would prepare young men – and from the 19th century onwards, women too – for key positions in society. Most travellers were younger than twenty, no more than boys for whom sowing their wild oats was implicit on their journey: the first lessons in love and gambling learnt.

Paris, and especially Italy, were the most important destinations on the Grand Tour. Travelling was time consuming and programmes were filled to the brim. Usually, the Grand Tourist’s voyage would last anywhere from six months to two years. The Venice carnival, Easter in Rome, an erupting Vesuvius had all to be seen and taken in.

To ensure the Tour’s success, the young traveller was assigned a bear leader (chaperone.) This would often be a man who knew their destination well and would show the little lord his way. Depending on the budget and the duration of the voyage, the Tourist might have been escorted by one or more chamberlains and a coachman. Many travellers hired a local to make sure that there would be at least one member of the party who could make himself understandable. The family’s foreign relations, local guides, or antiques dealers provided tours and introductions.

The Grand Tourist found himself in an endless stream of site seeing; too much, perhaps, to remember upon his return home. For this reason, most travellers wrote letters home or kept a travel log.

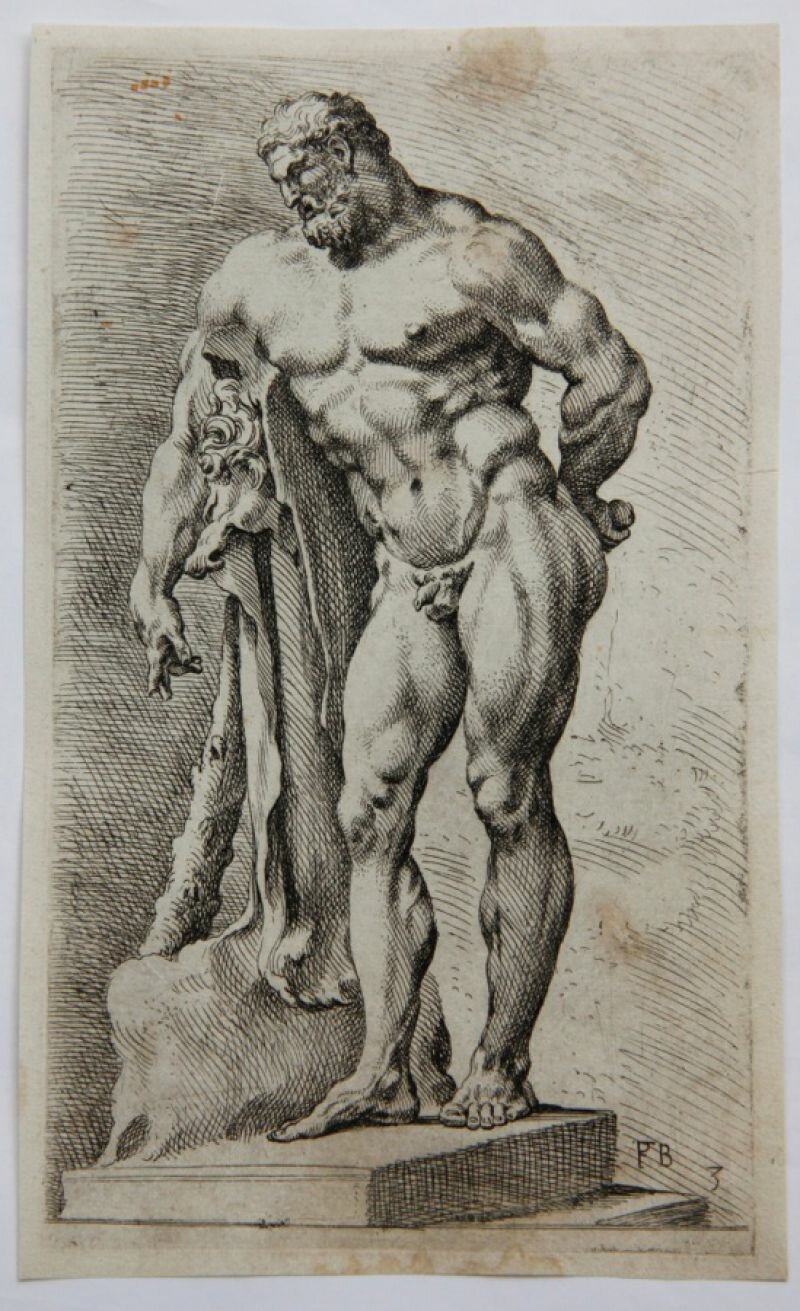

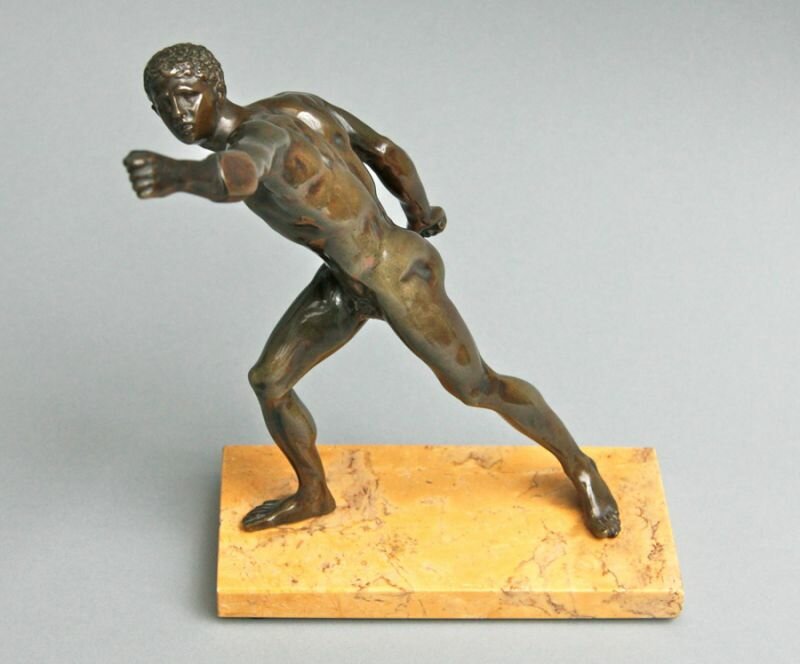

Of course, souvenirs that served as tangible memories of the trip were acquired along the way. Sometimes these would be original antiquities, other times the Grand Tourist would buy (scale) models of artworks, architectural structures, monuments, sculptures in bronze or marble, prints, drawings, paintings, and so-called dactyliothecae, made especially for this purpose.

The souvenirs gave status to their owners, acted as ‘conversation pieces’ during dinners with relations, friends, family members, and illustrated the Tourist’s gained knowledge and experience. Ultimately, they were used in art education and had a great deal of influence on the development of art and architecture. Every important art academy in the 19th century owned a collection of plaster sculptures, cast from famous sculptures from antiquity.

08.10.2013

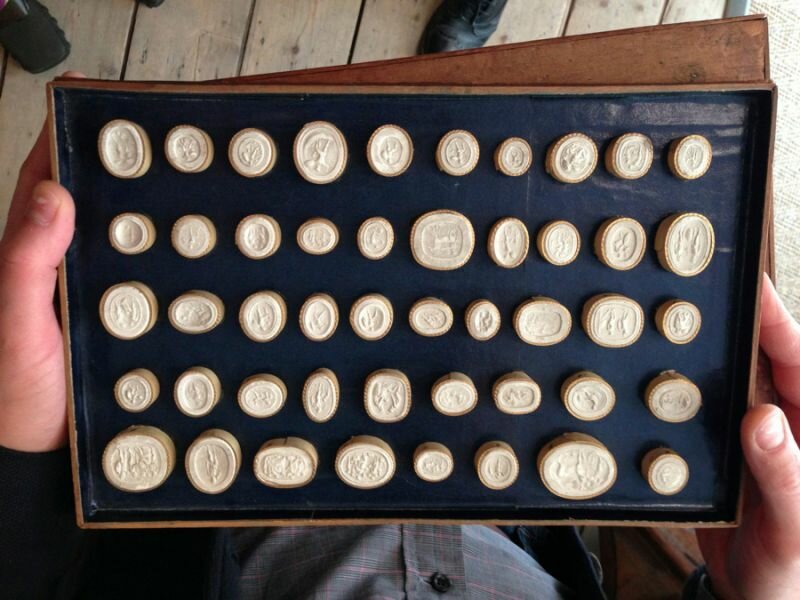

The dactyliotec is the equivalent of the modern day digital photo album. Dactylioteca were stacked boxes containing prints of gems bearing depictions of Roman emperors, philosophers or art works from for example Vatican museums. Most of the imprints, also called intaglios, were done in cast. Some of them were cast in a beautiful red sulphur paste.

The Grand Tourist started buying them from the beginning of the 19th century at specialized studios and could customize the content description to the latest scientific advances of his time.

Already during the 18th century P.H. Lippert gathered 13149 of these casts in three cabinets in the shape of books. He named the collection a dactylioteca, derived from the Greek word for depository for signet rings with gems. The Amsterdam drawing Academy bought one copy of Lippert in 1792 which is now part of the collection of the Rijksmuseum.

Famous makers of these 19th century collections of casts were Odelli, Liberotti and Paoletti. They all set up their studios in the same area in Rome between the Piazza del Popolo and the Spanish Steps. This was the area where most travellers found shelter upon arrival in Rome and was therefore called the 'English ghetto'.

A remarkable copy is the shown here: a set of prints of erotic gems. Since the first half of the 18th century there was a 'gabinetto segreto' in Naples, a secret cabinet that contained the excavations from Pomeï with an erotic tone. The cabinet has known a long history of closings and opening and was even closed with a brick wall in 1849.

This collection of casts is an extraordinary souvenir of a traveller who might have had the luck to find the cabinet opened.

08.10.2013

Pick up the plastic globe and shake it, and the world within it transforms into a snowy landscape, despite the bright blue sky within. They’re called snowstorms, but are also known as snowballs, snow globes, shake domes, water globes, or snow domes. Each name stresses a different aspect of the object: shaking, globe, water, or snow. The first example was shown at the world exhibition in Paris in 1878. These were made of glass. And the snow wasn’t made of plastic, but from flakes of rice, porcelain, bone, or wax. Since then, they’ve grown to be a true collector’s item; sometimes you’ll see whole windowsills full. One also comes across them in thrift stores. But why snow? And why would you collect one, only to throw it out?

Shake one and you’ll know enough. Each dome houses a small, adjusted world in which time stands still and everything remains the same forever.

In the globe you’ll see that which you’ve seen in the big world; that moment, that experience, that building, locked in a frozen state for eternity. That little world is yours. And because it’s yours, you can change it. The snowstorm that ensues is merely the symbol of that. Your thoughts can travel further, past your memories. Further than that one moment. Past the blue sky and the nameplate to the horizon, to where the snowflakes

Better than buying postcards or taking photos, snow globes are collected. At home their value is revealed. Not only does looking at the snow domes bring back memories, but the collector’s thoughts remain a voyage through which he travels. With one swift movement of his hand, Paris is not just the Arche de Triomphe and the Notre Dame, because there, behind the right tower, begins his Paris. The city of his dreams. The journey he once made to Canada and the United States likewise continue forever. Past the captured monuments of St. Louis, Minneapolis, Toronto and Montreal. Even past the idyllic coast of Nova Scotia. Further, always further, to buildings that will never exist, forests that have disappeared forever, and places that only he knows.

But one day, the globes will reveal their true identity. The cheap plastic begins to tear. The once clear water grows clouded, begins to evaporate, and turns into a sticky substance full of chemicals. The dancing snowflakes can no longer keep with the rhythm and lie at the bottom like dirty plastic bags. The collector, unconvinced of his defeat, once again picks up the snowstorm, tips his hand and sees that, actually, all his dreams come from Hong Kong.