Ladies and gentlemen!

I don’t have any images to show you, as I was too late in realising that I should have brought some. However, this might be a blessing in disguise, because those listening carefully will experience a flurry of images.

I’ll be frank: I don’t think that we live in an era in which illegality should be considered art’s driving force. Art itself is weak, she is not a factor of social importance and thus isn’t improved by illegality. This is not to say that one should not take a critical stance on world developments—but critical thinking is not the same as illegality. Illegality is necessary when hefty, oppressive laws are being enforced by hefty, oppressive law enforcers. But our problem is not that the political and social structures in which we live press too heavily upon us. Our problem is that the wielders of power can get away with far too much. Our model of democracy has been fine tuned to minute detail and it grows finer and finer yet. The level of bureaucracy that almost naturally ensues is a blessing for the powers that be. Within bureaucracy lies a turning point in which all is still democratic on paper, but no longer so in spirit.

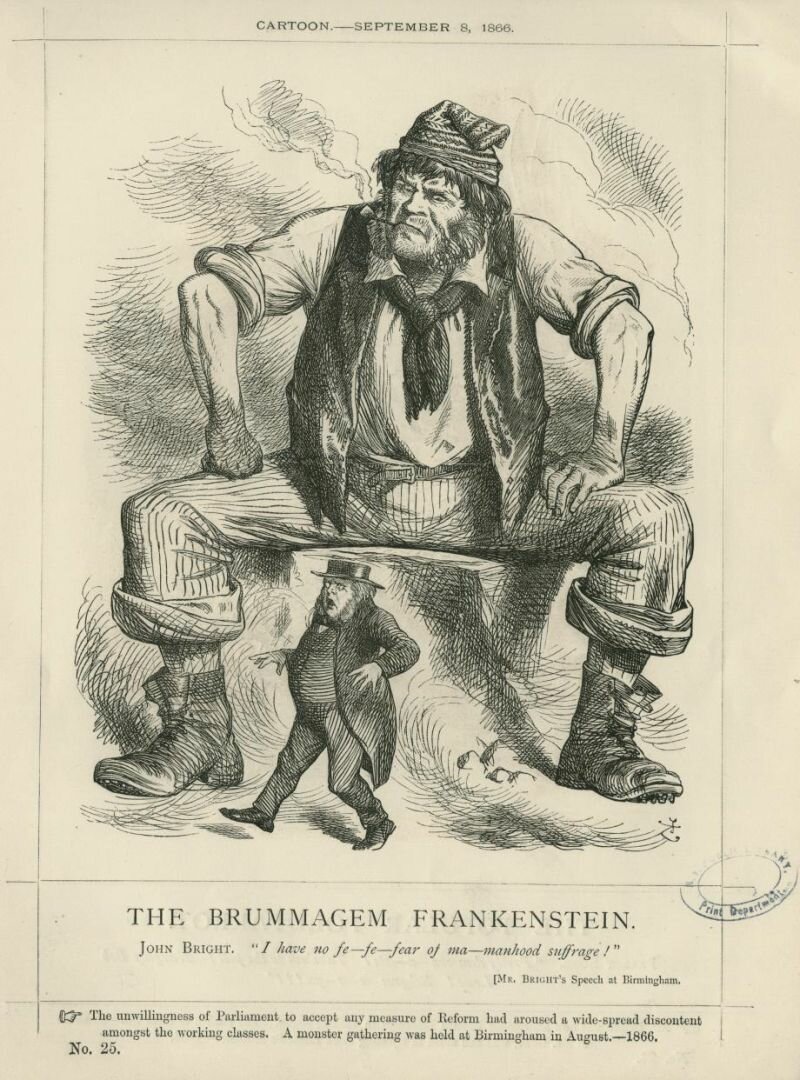

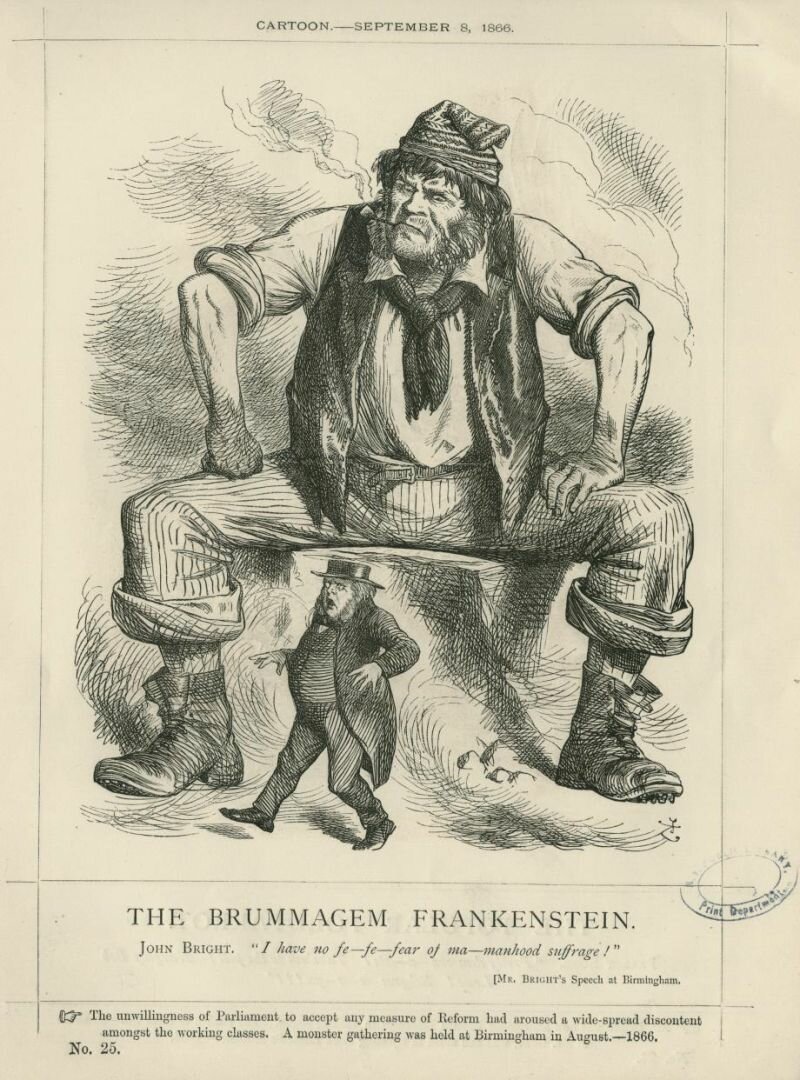

It becomes increasingly difficult to see the forest for the trees amongst the thicket of rules created to cater to each group and subgroup’s fair rights. And this is when profiteers and fraudsters strike. Bureaucracy is the illegality of power. This is where the cloaked retaliation takes place, where the tax collector’s alleged thievery is compensated, like when the areas that were agreed upon to stay leafy and green become construction sites, health and safety norms are ignored, and so on and so on.

Bureaucracy has made power schizophrenic. Although she may speak through the official language – the vocabulary of democracy – she thinks in outright ‘me, myself, and I’-terms. This is why their mouths are always dripping in deception, always the false smiles, that badly concealed inner pleasure at knowing that the herd of listeners is being fooled once again, with eyes wide open. You merely have to watch Bush speak for a few moments to see through him. I won’t even begin to say anything about our own leaders.

What it boils down to is that democracy isn’t as much a tool to prevent the imbalance of power, as it is a tool to make power something that’s unattainable. In the end, who truly holds the power? You could say it’s “the big countries” or “the multinationals,” but who are they? Power is more impersonal than ever and is no longer tied to certain political ideas or ideas about society, nor is it bound to tradition. The only idea still linked to power is money. At least, this is what it’s like in the West. We like to think that outside of the West, power is still based on tradition. Religious tradition, for example, which scares us to death. And we shudder to think that they might come here and take what they can of all that we’ve “built,” as they say!

Because we’re all too aware of how ruthless and greedy people can be. After all, we ransacked half the world in our glory days in the name of God and the motherland. But now the tables have turned, we’re none too confident, our population is largely aging, albeit with a great openness towards the world (we say,) but ultimately, we’re mostly defenceless and vulnerable from every angle. Are artists the ones to offer enlightenment through their illegal actions in this political landscape, which is generally seen as unsteady and threatening, where people prefer to keep themselves high and dry well before the skies erupt? That seems unlikely, to put it mildly.

Ambiguity about whom they’re targeting is the first problem. What is it they’re rallying against? I’ll name two examples of artists who are equally unsure of how to answer the question:

Last year I was invited to participate in a symposium about uprisings at the art academy at Enschede, AKI. As I approached the building in the morning, students were building a gigantic artwork out of dozens of shopping carts stacked on top of one another. While speaking to one of the tutors inside, we were interrupted by one of the students. He came to tell us that they wanted to merge the school with the artwork, but in order to do so; they’d have to shatter one of the windows. “Is that allowed?” he asked the tutors. “Throw in a window? I don’t think so,” was the reply. “Okay, then we won’t,” the student responded, before meekly wandering off.

And with this incident, the level of upheaval (or lack thereof) was set. The symposium continued with little but tepid mumblings. Out of sheer insubordination I yelled out: “There must be more authority!” The next day I received an enthusiastic email saying that they had highly appreciated my talk, and that I’d said many “valuable” things. Out of gratitude, my face was plastered on the cover of the AKI’s yearly report, published in book form. That’s just how easy it is to be famous; all you need to do is declare that the revolt won’t be happening. Tonight I’ll say it once again, but I hope this time will result differently, and Mister Motley will retain its honour.

“An international curator pushes a ragged looking pink newspaper at us. Survival Guide for Demonstrators, is printed at the top. The paper is full of tips for demonstrators: where to find the best demonstration spots in different cities, train and bus routes, safety precautions, your rights if you should be arrested. In a corner, a thank you is printed to a few big curators and a very contemporary museum. Aha! This is art! It lacks any explanation for what we should demonstrate against. That would make the paper a political statement, and that’s not the point. “I like demos,” the artist, Jota Castro, mentions. “The more alternative, the merrier.”

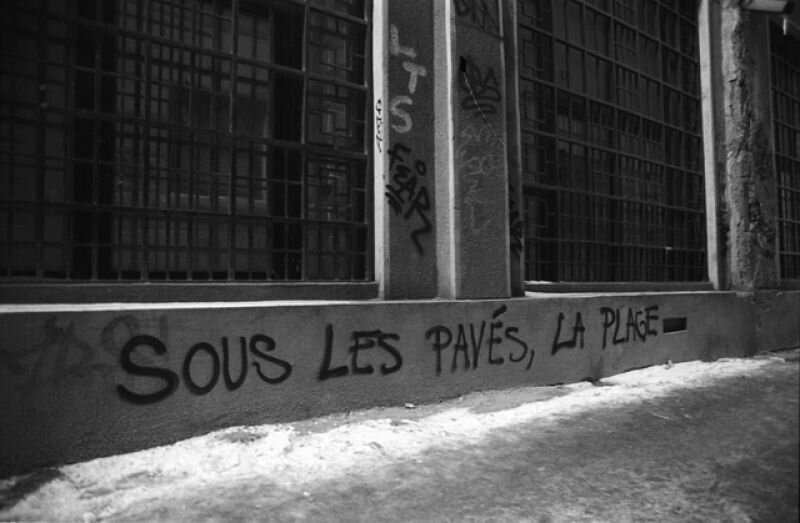

Yeah, fun, demonstrate! It doesn’t matter what we’re rioting against, because this is a conceptual work, and that means we basically only care about the idea, in this case of being playful and alternative. This is how we should interpret the Utopia Station. It’s a corner of the Biennale, overtaken by a chaos of poster, folders and information stands. In a whole, the work is reminiscent of the action years of the sixties, but in this contemporary case it lacks any sort of goal. Nothing refers to actual Utopian ideals. A vision of a future world is nowhere to be found. What we do see is that art wants very badly to engage itself. It just doesn’t know how to or with what cause.

The aforementioned condition is what the theme of this night likewise touches upon. We’re asked to speak about phenomena like graffiti, stickering, stealing exhibitions, but it’s not clear what graffiti we’re talking about, nor what the art stickers say, nor which exhibitions should be stolen. Or are we implying that graffiti art is already inherently artistic and illegal enough by its nature? Now, there have been many beautiful graffiti works, like those that embellish the iron shutters that otherwise turn our cities into rodent holes at night. But there’s also an enormous amount of graffiti shit that has contributed to the degeneration of our cities.

Like so many others, I too, am of the opinion that the privatisation of the Dutch rail company has been mostly detrimental, however I don’t feel that the artist who sprayed FUCK HELL all over the seat I sat across from the other day made any impact whatsoever. FUCK HELL, God forbid, how does one come up with that? These actions are nothing more than a reflection of the lack of taste that have been pumping junk architecture (predominantly) into the outskirts of our cities, besmirched our inner cities with a wildfire of advertising. A few years ago, the city of Paris made the wise decision to ban all street advertising at the Champs Élysées. But then again, France is a rather authoritative nation where the authorities still execute their decrees. In our thoroughly democratic nation, we handle things differently. The city of Rotterdam, for example, has urged its businesses to plaster more advertising to their streetlights. It seems that the city housing the biggest harbour in the world is unable to pay for its lighting, and so the MP deemed it fit to set up an advertising construction to compensate. Brillliant, the city council must have thought, solved!

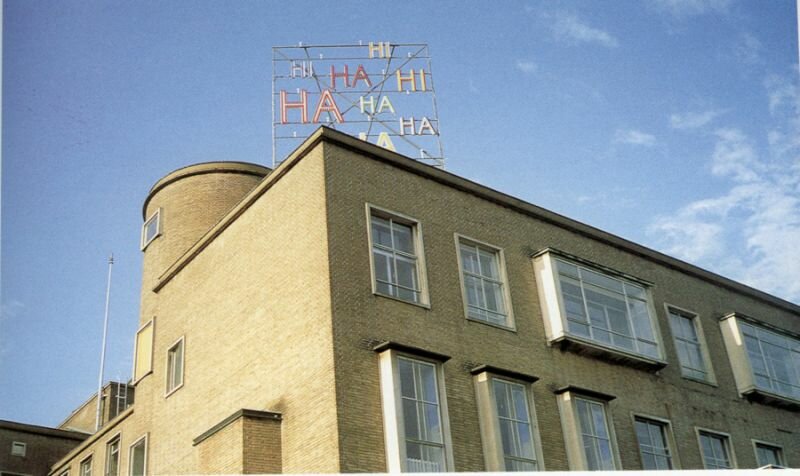

Thanks to government encouragement, the city is being saturated with images that are wholly vacuous and empty. As if we won’t eventually be collectively affected by the emptiness. As if this visual environment won’t slowly drive us towards a mental vacuum. You could call this the legal illegality of power—now, there’s something artists should revolt against.

But that’s easier said than done. After all, we’re trapped in a world of exponential impatience, in which images that don’t stick to our retinas for more than a nanosecond are deemed nearly worthless. The answer that artists seem to have proposed to this concerning development, is to express themselves in the same language as the images that they are trying to combat: fighting fire with fire. An artist who consciously applies this strategy is the Italian-Swedish director Erik Gandini, who won the Silver Wolf last year with his documentary, Surplus. Gandini promisingly claims – and this is also the subscript to his film – that we are being “terrorised into consuming.” Surplus is what you could call a visual manifesto against globalisation. In fact, an important spokesman for the anti-globalisation movement, John Zerzan, also appears in the film.

And yet the film, Silver Wolf or not, has failed as the analysis of a certain world condition. As poignant as Gandini is in finding images and digital manipulation, he fails to direct the images towards a specific standpoint, leaving one questioning if he even has a vision at all. The ringer lacks a bell. He sketches Cuba as paradise on Earth, completely naïve, as though we’re living forty years in the past, in the time that Harry Mulisch returned from Cuba golden bronze and praised Castro to the heavens. Could it be that Gandifini’s intentional use of advertising language is exactly that which hampers the film? After all, doesn’t advertising contain the fable-like ability to manoeuvre highly aesthetic images with the most gruesome content to political neutrality (like Benetton)?

These are important questions for Mister Motley, if you ask me. Because the magazine, with its focus on beautiful and attractive images, also seems to have been affected by the fear that only the visual cortex grants access to our brain. This is dangerous, because if you’re not careful you’ll be completely immersed into the free and happy image culture, even if your initial intent was illegality,

I thank you.