Carnival...the horror...the horror.

What I wonder is, why do I find carnival so horrible?

Oh wait, it’s not that I find it horrible. I find it revolting.

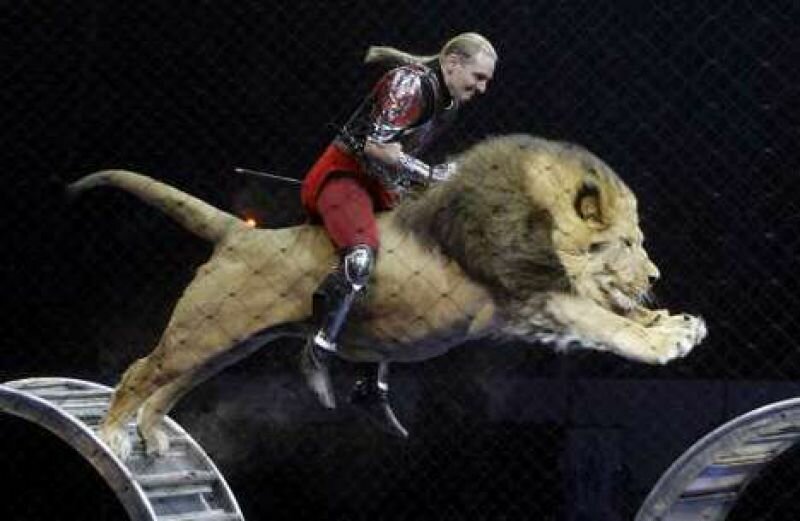

In essence, it’s a great concept: “A short period of chaos, the temporary removal of social hierarchy. An exchange of roles and the exaggeration of the behaviour associated with the assumed role.” This gives the notion of some sort of social upheaval, which I’m always highly in favour of. Instead of social upheaval, though, chaos manifests itself in the manifold groups of people taking to the streets, behaving super strangely, clothed in bizarre outfits that pay no heed to any sort of vanity, who begin their drinking at 10 in the morning to rid themselves of last night’s hangover so that the party may continue unfettered. Thankfully, neither small-mindedness, intolerance, exclusion nor negativity impose obstruction for this daze of intoxication. When entering a mass of partying carnival-goers, you will immediately be immersed and welcomed, becoming part of the whole. You and the cavorting mass will become one.

You’ll see your neighbour joyfully frolicking his way past you in a failed attempt at a smurf outfit and you think to yourself, “There’s a spark of life inside him yet.” He’s likely thinking the same when he sees you in your homemade “Domino’s Pizza” suit. You spot the cashier from the local supermarket in passionate embrace and watch her green face paint mesh into her male fellow partygoer’s pink lipstick. Behind them, an extremely ugly clown is engrossed in an equally passionate embrace with a lamppost (not a costume, just a lamppost) while a carnival float in the shape of a nose passes by in the background.

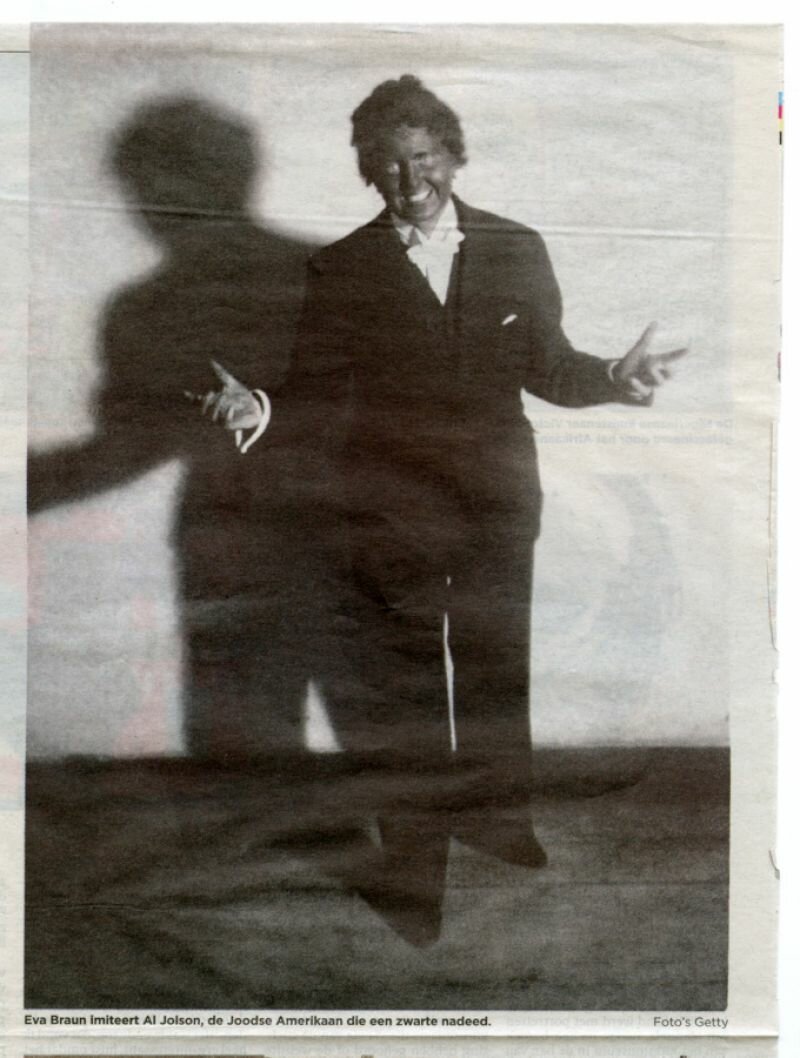

There are many different versions of the history of carnival. At the core of just about every carnivalesque festivity lies a social or ecclesial hierarchy. There must be at least two parties of unequal social or ecclesial order. Because where there’s an authority, there are (with a bit of luck) a number of subjects or followers willing to emulate the wielders of power. The church’s authorities believed it would be beneficial for the “normal believers” to experience what life would be like when “the devil, witches, jesters, the antichrist, and the eccentricity in man” would rule during a short period of a few days of festivities before Ash Wednesday. They wanted to show the people how the world would fall to ruin and the depravity of a life lived solely by earthly principles. The logic of this reasoning might rightfully confuse you, as it basically implies the same as saying: give a man a million to do with what he wishes for three days and you’ll see, he’ll come crawling back to our church with his tail between his knees!

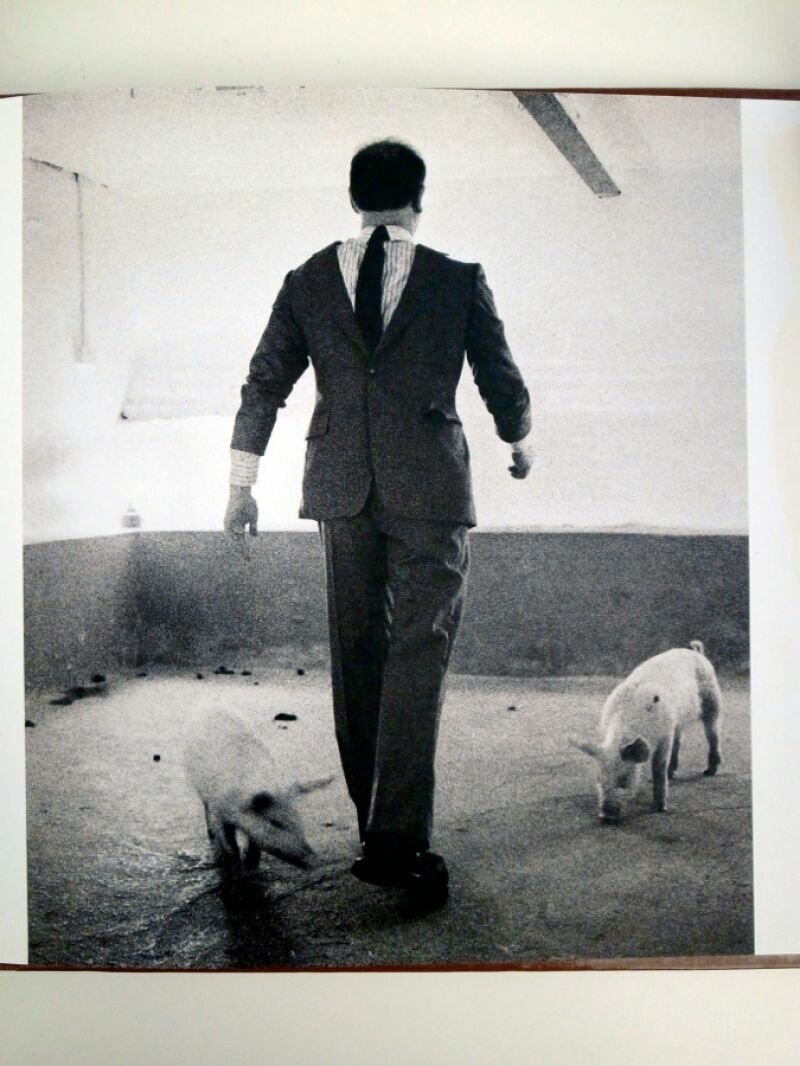

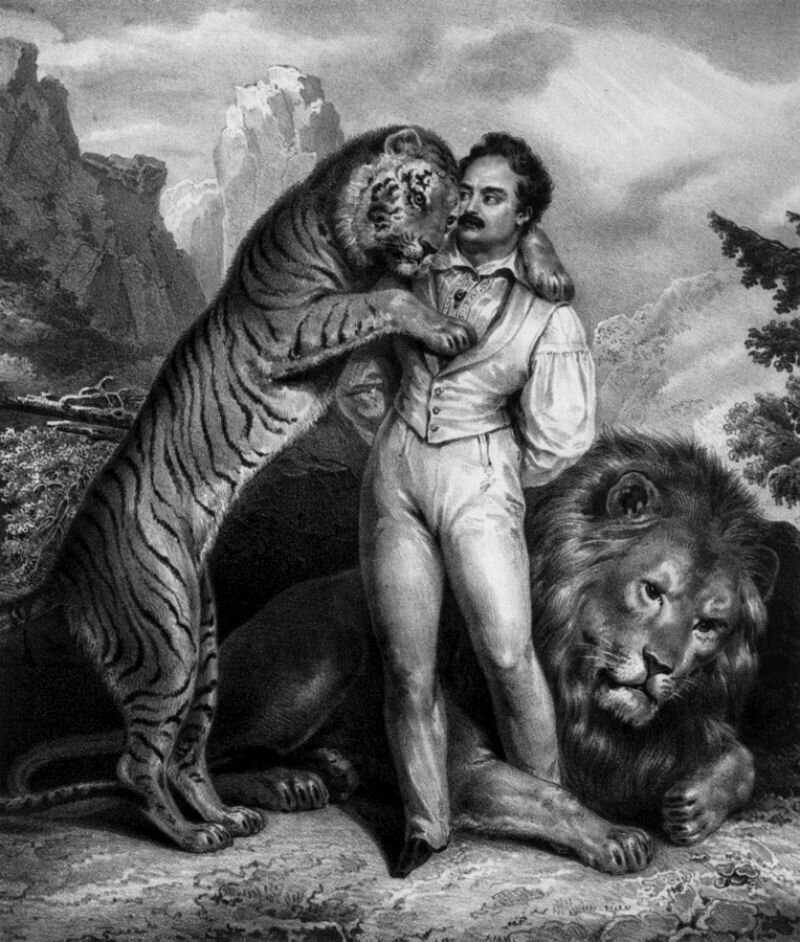

“A short period of chaos, the temporary removal of social hierarchy. An exchange of roles and the exaggeration of the behaviour associated with the assumed role.” Anthony Howell (1945) is a British performance artist who plays with reversals in his work. In the performance, The world turned upside-down (1998) he walks around in an austere, classic men’s suit worn backwards. Two piglets that scurry around him, snorting and grunting, accompany him. Howell corrects his outfit as he walks. With his backwards suit and his tie on his back, he tries to turn his coat around, and in doing so the sleeves of his jacket nearly end up as trouser legs. The piglets symbolize man’s lowly self-indulgence and literally deliver the soundtrack for the performance. After the performance is over, Wiener sausages are served to the audience. By wearing this suit, Howell seems to be conforming to certain social values, which he immediately sabotages this by abusing, as it were, the suit on his body. He’s wearing a suit, but at the same time, he’s not.

“A short period of chaos, the temporary removal of social hierarchy. An exchange of roles and the exaggeration of the behaviour associated with the assumed role.” I suppose my repulsion lies in the following: a SHORT period of chaos? The TEMPORARY removal of social inequality? What about the remaining 365 days? It’s precisely this short window of opportunity that I disagree with. Four days where all are licensed to act weirdly, dress bizarrely, and anything is possible. People, this no more than a drop in the ocean! Oh artists of all nations, carry on, carry on. On all the other days it’s your duty to reveal the world in a different light, to turn the inside out and the upside down!

“Defining, but also the forgetting of time is very important during carnival. The clock is overcome. When we celebrate carnival, we are greater than time. This is nearly metaphysical. You could almost say my book is also about Zen Buddhism.” As said by the Amsterdam author Jan van Mesbergen (1971), following his novel Naar de overkant van de nacht (loosely translated to: To the Other Side of Night,) that takes place in the daze of the carnival in Venlo that he visits annually.

(Oh artists of all nations, carry on, carry on!)