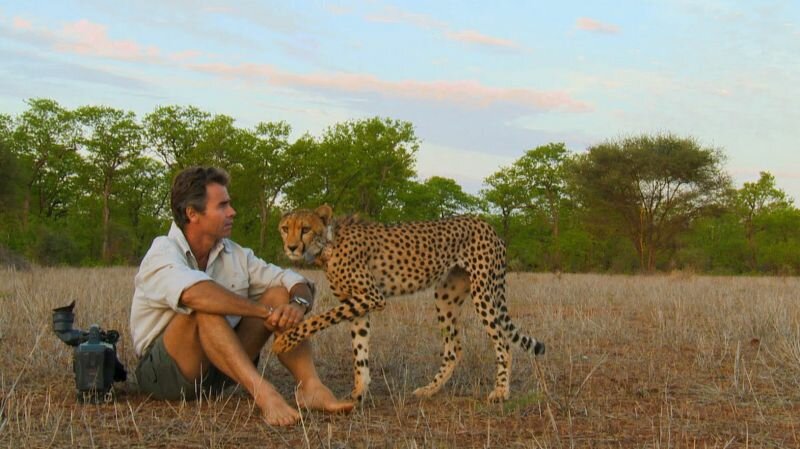

As a child I had the wish to befriend a Siberian tiger. I can completely relate to that inner desire that many people have to be among wild animals. It's an amazing thing to see it when it works: some people manage to swim with tigers and hug wild bears.

When those two worlds meet or collide (sometimes resulting in the dismembering of an arm or of bodies being crushed,) I sense the overwhelming beauty of the situation. I often find that beauty on YouTube. There are hundreds of clips of people living with wolves, juggling with tigers. One of the videos takes place in a zoo.

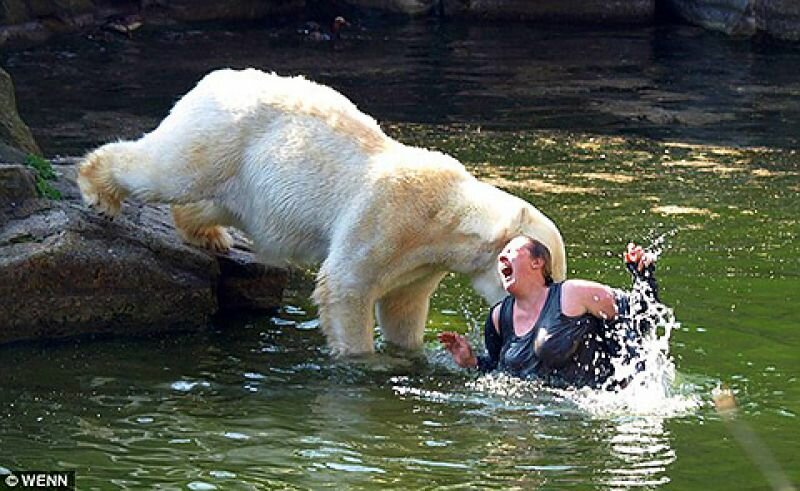

A polar bear gets hold of the chubby leg of a typical tourist. The women had climbed over the fence and wanted to look at Blinky (his name) up close. It turned out to be a risky situation.

For the tourist, this was not a very logical thing to do. For the polar bear, it was.

My imagination is not only triggered by the fact that

From the safety of my bedroom, my imagination is not only triggered by the fact that I’m watching a polar bear named Blinky adorably sink his teeth deeper into a tourist steak on Youtube. But it’s also that I get to see Blinky as a real animal.He comes to life. Blinky momentarily experiences that his true nature lies within the borderline between the pathways on which visitors stand gawking at him and his cage.

Call it instinct, call it boredom. But what Blinky does, is not easy to explain. It just is. The name Blinky disappears with each bite he takes. Because in between the bars of his cage lies the real world where the bear might know his name or he might not.

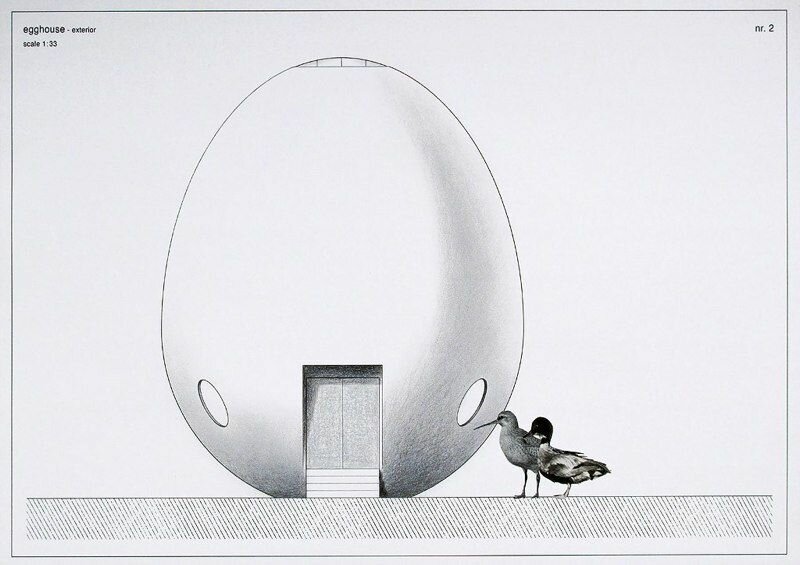

John Berger writes that animal have been marginalised in our society because of our tendency to turn animals into products of our life. It relates to the given of dogs strongly resembling their owner. And in that margin, wild animals explore the borders of their imprisonment. A drunk tourist in a football shirt with waxy spikes on his head bangs on the glass wall surrounding a wild animal that lays on his back like some couch potato. 'For the bloody love of God, do something!' roars the man.

I'm thinking of the man who lives inside a whale. According to people, the bars of imprisonment in Disney movies or Biblical stories mainly exist out of the skin or mouths of the animals, trying to penetrate or open humans. Just like Jonah.

The impossibility of being with wild animals makes me want to try it myself. I think people who want to pet tigers are crazy, but I am tempted to try it myself. To kiss each other like lovers, press our heads against each other. Our brains should blend. The twisting of the tongue, the muscle in our body that can turn miniscule particles into big things.

Fortunately, a dog has a shape and doesn't float through the room like batter. Luckily we get to adore and pet our dogs and cats. And maybe even send them into space for the sake of experiment.