I owe my first encounters with the frog theory of Brisset (a man who was declared Prince of Thinkers for having proved on linguistic grounds that man descends from the frog) to ’Pataphysics, the science of imaginary solutions that has been developed by the French writer Alfred Jarry (1873-1907). ’Pataphysics plays with philosophical notions, scientific discoveries and technical attainments. In this way Jarry invented a de-braining machine, developed Perpetual-Motion-Food, and calculated the surface of God.

Jarry was not only influenced by the sciences, but also by morosophers like Brisset. And Victor Fournié who claimed that the same sound has the same meaning in all languages, brought Jarry to the fundamental insight that IN-DUS-TRY means one-two-three, in all languages.

’Pataphysics is, in the first place, a science; according to Jarry it is science par excellence.

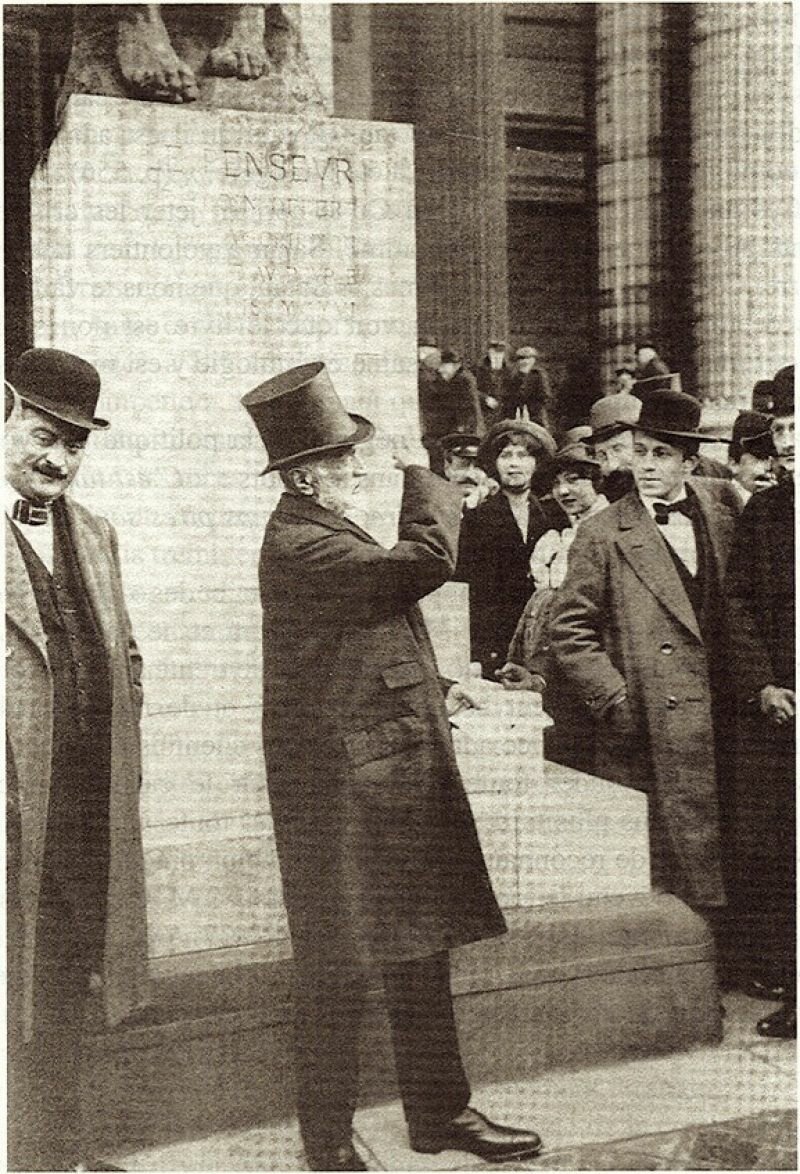

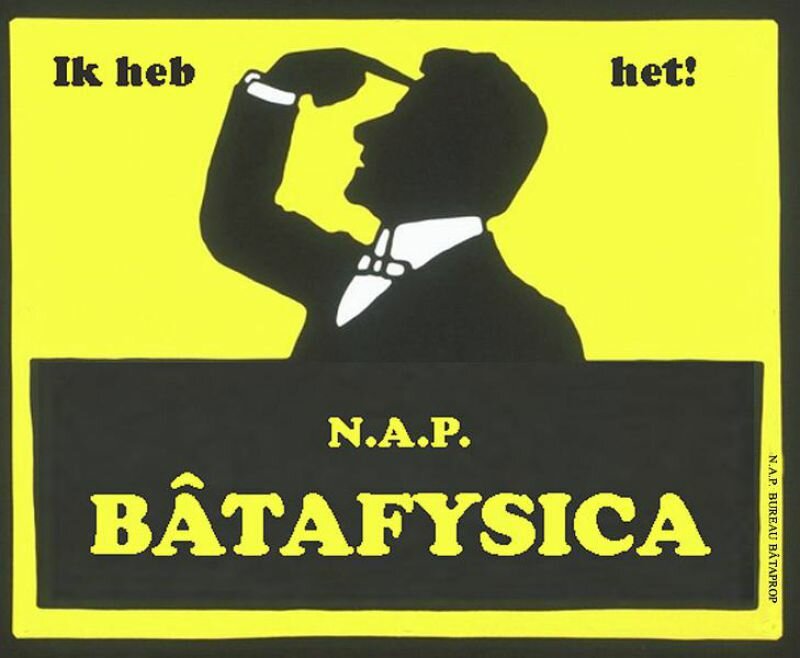

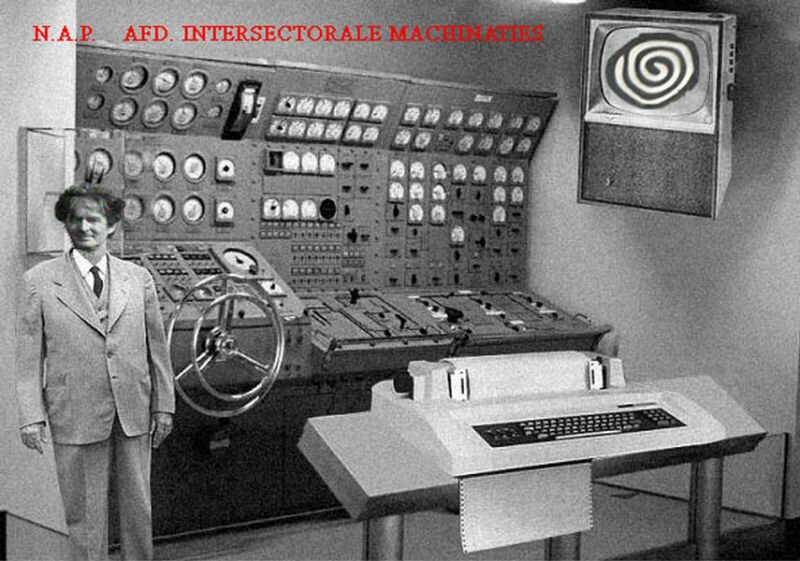

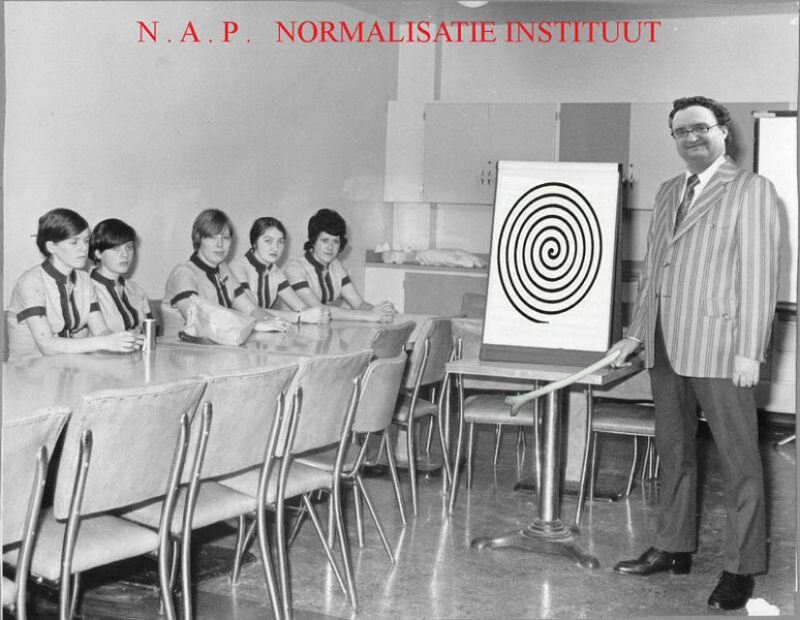

Several institutes for ’Pataphysics have been founded: Collège de ’Pataphysique in Paris, and in the Netherlands, in utmost secrecy, De Nederlandse Academie voor ’Patafysica, the NAP, also called Bâtaphysics. Unlike the Dadaists, the bâtaphysicians did not feel the need to rebel or revolt, as Bâtaphysics celebrates the equal value of all situations. Other than the surrealists, the bâtaphysicians do not seek refuge in the subconscious, although they appreciate it as an imaginary solution; not only do they view daily life as a hallucinatory adventure, they also regard

logos and rhetoric as the quintessential psychedelics. Furthermore, the NAP embraces Dadaism and surrealism as pataphysical phenomena.

Pataphysicians travel across the planet with a keen interest in everything they find in their way. They assemble the wildest collections, impose order without ever attaining any, and leave behind a trace of imaginary constructions. Pataphysicians, just like morosophers, explore realms that elude the maps of regular science. The researchers measure the immeasurable, put the unheard-of into words and instrumentalise the incorporeal. And, vice versa, they manage to expose in the most banal object an unexpectedly pataphysical dimension. They disclose the area of possibilities where every occurrence is ruled by its own laws. The pataphysicians are collectively astonished about the

consensus omnium and defend one man-science. Anyone can become a member without tricolon, circumcision or piercing. The only effort one must make is to donate generously.

Is Bâtaphysics the missing link between art and science? Bâtaphysics is not art; all art is – consciously or not – pataphysical. All the more so when she exposes new regularities or laws. With the Expertologists of the Insect Sect we can say: Bâtaphysics is not art, but real.

The NAP approaches all phenomena with the same curiosity. Everything is investigated for its unique natural laws, for what makes it something exceptional and monstrous. Every ordering produces its exemplary demons, but even order itself is monstrous. According to Jarry, monstrosity defines beauty. Every aesthetic theory is a teratology. Bâtaphysics holds that nothing normal or abnormal exists, every event is equally monstrous ergo beautiful.

‘A camel is a horse designed by a committee.’ If necessary, the NAP single-handedly creates the deserts in which the camel appears to be the ideal animal.

Bâtaphysicians appreciate time, space, identity, profession, nationality and other beacons that man steers by in daily life as imaginary solutions. If bâtaphysicians use a pseudonym, a mask or a disguise, if they pass beyond trodden pathways, or if they use a different calendar, it is therefore no protest against the status quo, but an attempt to taste and challenge the bâtaphysical character of existence.

Bâtaphysics solves problems that are experienced as problematic by nobody. Moreover, Bâtaphysics is like Expertology in that it frees us from problems by turning them into emblems, into polyhedrons of ideas.

’Pataphysics was born out of a fertile mixture of science, faith, art and morosophy; in other words, these signs of human inventiveness are pataphysical attempts to get to grips with the idiocy of existence.

On the one hand, ’Pataphysics can lead to remarkable creations. On the other hand, ’Pataphysics stands for an ethos. ’Pataphysics is no philosophy or literary view, but a perspective. Put more strongly: ’Pataphysics has to be lived by first and foremost. This does not mean that you display eccentric behaviour, but that you are aware in your every act, no matter how banal, of the pataphysical character of what you do and think.

You can thus write most ordinary books, go to church, have intercourse, be married, read the papers and still be a pataphysician. It is not about a resigned detachment, nor is it about an ‘innere Emigration’ or postmodern irony, but about an awareness of the fantastic nature of your behaviour and a keen eye for the exceptionality (idiocy) of even the most common routine. In other words: the world is really the true Academy for ’Pataphysics. Everyone and everything is pataphysical, the only difference is between those who are aware and those who are not. A difference of almost nothing makes a whole world of difference: routine that is approached ignorantly and passively numbs the mind, but the same routine experienced with an awareness of the inherently pataphysical character of it can lead to enthusiasm, even ecstasy.