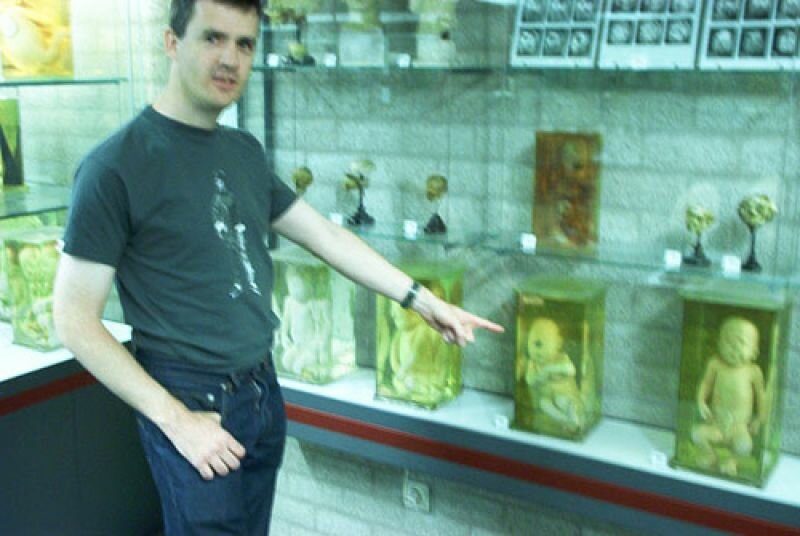

An exhibition has been installed in Museum Vrolik, but the shown collection has not yet been described in detail to the public. Hence this ‘self-guided’ tour, that leads past thirty highlights in the field of embryology, congenital anomalies, pathology and the history of collecting.

1. Embryo without membranes (5 weeks old). This is the smallest unborn human in the museum that can be seen with the naked eye. At five weeks into the gestation, the vital organs and tissues are, in principle, in place, such as the heart, liver and neural tube (the predecessor of brain and spinal marrow). Yet the face, arms, and legs have barely developed. Compare this embryo to the wax model (nr.8) in the bell jar on the glass plate on the upper right.

2. Young foetus (8 weeks old) in its inner membrane (amnion). Already at eight weeks after fertilisation, all tissues and organs are in place and we no longer speak of an embryo, but of a foetus. In fact, the foetus – no longer than 2 cm – only has to grow in size from now on. Face, ears, fingers and toes are already recognisable in this specimen. (collection Woerdeman 1934)

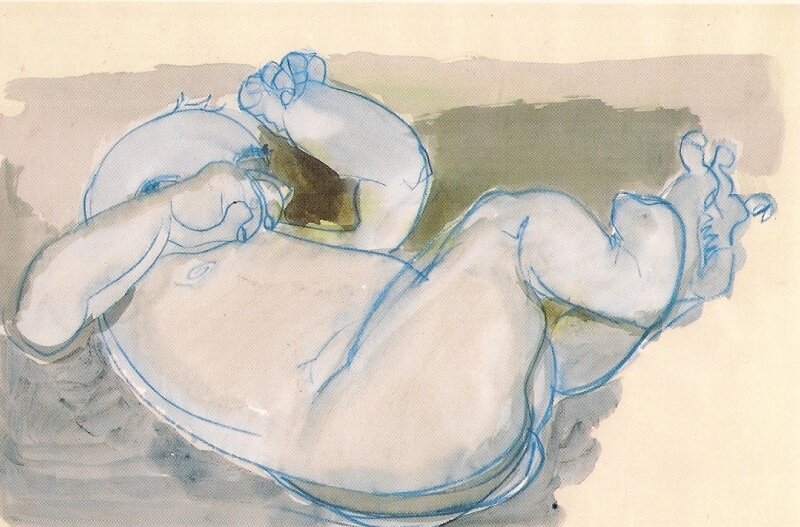

3.

Foetus in the uterus, with opened membranes (5 months old). The inner membrane, the amnion, contains the foetus in its fluid. The inner membrane, the chorion, forms a whole with the placenta (see also specimen to the left).

4. ‘Siamese twins’ is really a misleading term for a pair of twins joined in utero. The name finds its origin in 19th century Thailand, called Siam, where the conjoined twins Chang and Eng Bunker. Chang and Eng travelled the world and became so famous as ‘Siamese twins’ that this name would be continued to be used after their death for all connate twins. Just as this specimen, Chang and Eng belonged to the group of twins that are joined at the front of their torsos. Thoracopagus means ‘stitched together at the rib cage’. On the inside, it is also possible for organs, such as heart and liver, to be conjoined. Compare this thoracopagus to other Siamese twins (and skeletons) to see in which other ways the two bodies can be conjoined. (collection Vrolik)

5. Lithopedion or Stone Baby. A lithopedion starts as an ectopic pregnancy: the implantation of the embryo into the uterus does not occur, as it gets stuck in the Fallopian tube. This happens in 98% of all cases of this complication. It is very rare whenthe embryo burrows into the abdomen, as is the case here. Here, the foetus can reach a considerable size. When the foetus dies, sedimentations of calcium can encapsulate it, thereby petrifying it, as it were. (origin unknown)

6. Development of brain. A series of heads of foetuses and new-borns of which part of the skull has been removed to show the brains. As the foetus grows older and the brain gradually develops, an increasing number of furrows and coils appear. This development actually continues until long after birth. Compare the brains of the foetuses and new-borns with the brains of adults (on the shelf below). (collection Bolk)

7. Cyclops. Cyclopia is a congenital disorder in which the normal development of the brain is disturbed in both cerebral hemispheres. As a consequence, especially the parts of the brain that are centrally located and the body parts that are connected to these, such as the facial bones and nose, do not develop well. The eyes, which are normally formed more to the side of the face, end up in the middle, fused to one central eyeball. There is some variation in the appearance of Cyclops. Sometimes there is a proboscis (‘trunk’), a non-functioning deformed nose; sometimes there are two eyes, but very close to each other; sometimes the eyeball has two separate pupils. The variation in Cyclopes is also apparent from the series of Cyclops-skulls. The skull located on the far left is that of a normal new-born. (collections Vrolik and Bolk)

8. Development of teeth. This series of upper and lower jaws shows the development from deciduous teeth to permanent teeth. It is notable how the permanent teeth are present in the jawbone long before they erupt. When big enough, they slowly press away the deciduous teeth. The latter will become loose and fall out one by one. (collection Anatomical Museum Waag 1856)

9. Skull bones. Human skull from which all skull bones have been taken apart and, using brass plates and screws, reassembled. It is notable how the face is built up from many different bones, most of them very small. The part of the skull that surrounds the brain consists of a relatively small number of larger pieces of bone. The bones are normally connected with skull sutures, which are somewhat similar to zippers. (collection Anatomical Museum Waag 1856)

10. Hydrocephalus. A Hydrocephalus, commonly known as ‘water on the brain’ emerges when the normal circulation of brain liquids (liquor) is disrupted in the brain and spinal marrow. Often, a small tube (called the cerebral aqueduct or the aqueduct of Silvius) that carries liquid from the brain to the spinal cord is obstructed. The consequence is that the amount of fluid entering the brain increases continually, but does not leave it anymore. The brains are then pushed outwards and the skull grows to facilitate this. Without medical intervention, this deformation leads to severe mental impairment and often to death. The most important contemporary treatment consists of the placement of an artificial tube that drains excessive brain fluid. (collections Vrolik and Bolk)

11. Tightlacing Liver. Three livers, deformed by the wearing of a corset. In the 19th century, corsets were meant to provide their wearers – mostly women- with a slim waist as dictated by the fashion of the times. Enduring pressure from the corset resulted in deformations of the rib cage, lungs, diaphragm, and liver. The compression of the lungs and diaphragm led to breathing disorders, but the liver was not restricted in its functioning by the wearing of a corset. Corsets existed in all kinds and shapes. As a result, the deformations of the liver equally differ. The liver in the middle was partly divided into two by the corset (see the large cavity on the left side). (collection Bolk, 1906,1914, 1923)

12. Siren. A siren is a mythical creature from Greek mythology. Just like a mermaid, the siren is human on the upper side, fish on the lower. Sirenomelia is a congenital syndrome that in respect of shape reminds strongly of a siren or mermaid. There is only one leg, which sometimes ends in one foot, sometimes, two, but also often none at all. A remarkable detail is that sex organs and anus are usually lacking and that the pelvis and knee joint seem to have been placed the wrong way around. The knee thus bends forward. The cause of sirenomelia has not been well explained. Children with this disorder typically die during birth. (Collections Vrolik, Bolk, and unknown)

13. Penis. Two dried penises stuffed with wax, one with part of the (dried) bladder and part of the pubic bone (the front side of the pelvis) attached. The technique to inject tissue with (coloured) wax was invented in the 17th century by anatomist Frederik Ruysch and extensively applied until the 19th century. Especially tissue with many blood vessels or hollows was suitable to be dried after being pumped full, such as hearts, large arteries, placentas and penises. The penis consists, apart from a urinal tract, of erectile tissue that fills with blood during sexual arousal. (Collection Vrolik)

14. Chinese foot. The deformed lotus foot from the late 19th century can be seen as the Chinese equivalent to the tightlacing liver. For this beauty ideal the feet were fractured, often with young girls. The heel bone was pressed against the metatarsal bones, after which the foot was swathed. The result was a deformed, severely underdeveloped foot. Chinese women with lotus feet were very often prostitutes. The deformation made them hardly able to walk. Their clumsy waddle was deemed to be attractive by men. (collection Bolk, 1900)

15. Giant Hand. A plaster cast of the hand of a giant from Japan. Gigantism (also: giantism or acromegaly) is an overgrowth syndrome in which excessive growth hormone is produced. This happens in the pituitary gland, a small organ underneath the brain. The hypersecretion of growth hormone is mostly caused by a benign tumour in the pituitary gland. (Collectie Vrolik)

16. Harlequin Baby. Ichthyosis congenita literally means ‘congenital fish disease’. It is a genetic skin condition that must be very painful for the foetus. The aberration is caused by a severe swelling of the stratum corneum, the outermost skin layer that consists of dead cells or corneocytes. Motion in the uterus causes the thickened skin to rip in many places. The foetus on the left was born around 1841 and was described at length by Gerard Vrolik. (collection Vrolik)

17. Skeleton development. Foetus of around six months old, conserved in a clearing agent, a liquid that makes tissue translucent. The bones have been chemically coloured to render the bone formation visible. The skeleton of a foetus initially consists entirely of cartilage. During the development (before and after birth) this cartilage is slowly but gradually replaced by bone fibres. This foetus shows that the ossification of the skeleton (orange) has progressed considerably, yet is still far from completion. Especially at joints (knees, elbows, foot and hand) there are parts that still consist of cartilage and, consequently, are left uncoloured here. (origin unknown)

18. Dwarfism. Achondroplasia (literally ‘underdeveloped cartilage’) is a skeleton dysplasia, a genetic disorder of the skeleton. The main cause, as the name already suggests, is a disturbance in the development and ossification of the cartilage. This causes the vertical growth of the bones to lag behind badly. Very characteristic of this form of dwarfism is the relatively large head with a bulging forehead, a torso of relatively normal size and short, somewhat bended arms and legs. People with achondroplasia usually lead relatively normal lives (albeit with some modifications). There are many types of skeleton dysplasia that are more severe than achondroplasia; children with these more severe types most often die during birth (for more, see the vitrine ‘deviations of the skeleton’). (collection Vrolik)

19. Breakable bones. Osteogenesis imperfecta belongs, just like skeleton dysplasia, to the hereditary diseases of the skeleton. The name literally means ‘defective formation of bone’. The aberration arises by a mutation in a gene that is responsible for the formation of collagen (gluing agent) in the bone tissue. Without this gluing agent, the skeleton is very fragile: the bones of a foetus with this disorder will break with the slightest motion in the uterus. The fractures heal, but the bones come to be severely deformed. The skeleton on the right belongs to a special type of Osteogenesis imperfecta. That type has been described for the first time, and in this skeleton, by Willem Vrolik himself. This specific disorder is therefore named disease of Vrolik. (collection Vrolik)

20. Bezoar. Bezoar stones come from the stomachs of antelopes, gazelles or lamas. They consist of chalk-like substances and clotted hair. For a long time, the trade in these stones flourished, since they were regarded as an antidote to poison. Kings and other eminent gentlemen who feared poisoning had the stone set in gold for dipping in potentially poisoned drink. Because of their rarity and supposed powers, Bezoar stones were also a much sought-after item in rarity cabinets from the 16th and 17th century. (Collection Vrolik)

21. Bladder Stones. These two bladder stones, set in metal, are the oldest objects in the museum. The smaller of the two bears the following inscription: On the 27th December 1588 died Jan Jacopsen Dick, who went by the name of Schot, in the morning at six o’clock. This stone was cut out of his bladder, weighing a pound, and also a twig, both intact. A caption on the other stone says that on the 6th of May 1608, it has been removed from Elisabeth Fransen, 52 years of age, who passed away shortly after the operation. Bladder stones consist of all sorts of urinal salts and usually emerge when a kidney stone ends up in the bladder. Infections and the inability to fully drain the bladder allows them to gradually grow to enormous sizes. Bladder stones were removed by the stonecutter (lithotomist). A painful operation that was far from being always successful, as is also apparent in these inscriptions. If the patient did survive the procedure, he or she would often suffer from incontinence for the rest of his or her life. (collections Hovius and Vrolik)

22. Cart Wheel. Femur that was crushed by the wheel of a heavily loaded cart. Probably, the leg got jammed between the spokes of the riding cart and fractured in a complex way by the revolving motion. According to the anatomist Andreas Bonn, who described all bone samples from the cabinet of Horvius, the muscles in this specimen were torn, but the skin was still intact. The leg is a good example of what, in the 19th century, might have been a common incident, when horse carriages dominated the streetscape. (collection Horvius)

23. Kick of the Horse. Skull of a man that was deformed by the kick of a shoed horse. The anatomist Andreas Bonn states that the horse had delivered the blow in June 1750. The kick broke the cheekbone of the man. Consequently, a swelling emerged that gradually increased in size and reached from nose to temple. The eye became blind and bulged out of its socket. According to Bonn, nineteen years after the incident the swelling burst and the man died. (collection Hovius)

24. Kyphosis of Pott. A forward-bending kink in the spine is called kyphosis. This is different from scoliosis (see upper shelf), which is mainly a sideward curvature. The kyphosis of Pott is caused by an infection, mostly of TBC bacteria, in the vertebrae. Over time, the infected vertebrae are so consumed and weakened that they sag and, as it were, effectuate a fracture in the spinal column, which then bends forward. Kyphosis was named after English surgeon Percival Pott, who was the first to describe the disease. Not until the 19th century was it discovered that the same cause of the disease was already known as pulmonary tuberculosis (see the samples in formaldehyde below). TBC is still a serious and common disease worldwide.(collection Vrolik)

25. Rickets. Rickets is an excessive curvature and deformation of the bones that exacerbates over the years. It is caused by a deficit of vitamin D, a substance that is acquired through food or produced under the influence of sunlight. In the 19th century, rickets was common among the poor population in cities. Death by rickets was rare, except in one specific context: among pregnant women. The bone softening caused the spine to sag into the pelvic inlet. This resulted in a pelvis narrowed to the extent that women were no longer able to give birth. This was often discovered late and hence all kinds of complications occurred during labour – the child typically died and the emergency interventions of doctors often caused bacterial infections: childbed fever. Rickets was thus a frequent cause of death for both mother and child in the 19th century. It is no coincidence that the collection of Gerard Vrolik contains a large amount of ‘rickety’ female pelvises. (collection Vrolik)

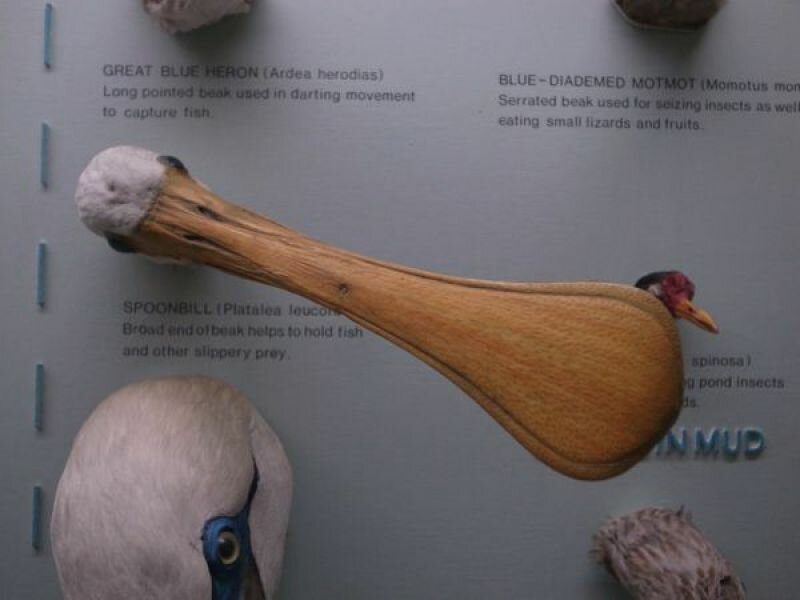

26. Vrolik Cabinet. Whale eye, lion heart, giraffe tongue and many other organs of a wide range of animals. It was mainly Willem Vrolik who showed interest in animal anatomy, as he kept the organs of basically every animal that he dissected, either dried or preserved in formaldehyde. In this way, a sizeable collection gathered of what is called ‘comparative anatomy’: by way of comparison of the same organ in different animals, one gained insight in the structural similarities and differences between all those animals. (collection Vrolik)

27. Napoleon’s Lion. The skeleton of the lion that was once part of the collection of live animals belonging to Louis Napoleon, king of Holland from 1806 to 1810. In 1809, this animal collection found its dwelling place in the botanical garden of Amsterdam, of which Gerard Vrolik was the director. When the lion passed away, Gerard Vrolik was allowed to dissect the animal and to keep the skeleton. The skeleton of the lion is posited prominently in a so-called ‘chain of life’, a series of skeletons and skulls of vertebrates. Father and son Vrolik were of the view that all living creatures were created according to an order, namely a chain or ladder that ranged from the least perfect to the most perfect creatures. In this case, it lead from fish to, ultimately, apes and man. (originally collection Vrolik, courtesy of NCB-Naturalis)

28. Young chimpanzee. Skeleton of a young chimpanzee from the collection of the anatomist Lodewijk Bolk from Amsterdam. Bolk developed a strong interest in human evolution. How did man originate from an apelike ancestor? Bolk compared skulls, skeletons and prepared samples of humans and apes and came to the surprising observation that the human body, especially the structure of the skull, had much more in common with the equivalent physiology of young apes than with that of mature apes. Bolk concluded that man must derive from an ancestor that had physically remained an infant, but was able to procreate. In Bolk’s words: “man is a sexually matured ape foetus.” (collection Bolk 1925)

29. Piltdown. Plaster cast of the Piltdown skull, one of the greatest cases of scientific fraud in history. The fossil remains of the skull, a piece of the brain-pan and half a lower jaw were found in a quarry in Piltdown, England. The find was immediately characterised as the missing link in the evolution of man. Plaster reconstructions of the entire skull were made at once and disseminated across the whole scientific world. Museum Vrolik also purchased one, in 1924. Although there was already some doubt about authenticity, the fraud was not unmasked until 1955: the skull bones appeared to derive from a medieval man and the jaw of an orang-utan. (collection Bolk 1924)

30. ‘Vivat Oranien’. Tattoos preserved in formaldehyde are rather documents of the times than anatomical specimens. Especially if the tattoo contains dates or text. A tattoo that says “Atjeh 1873-74” refers to the War for Atjeh. The owner probably served in that war and possible experienced love (the dark-haired lady with the hibiscus). 50 years after the tattoo was done, the man passed away. The tattoo “vivat oranien” with the orange tree stems from the first quarter of the 19th century. It possibly refers to the years around 1815, when The Netherlands became a sovereign kingdom with the advent of William the First, or to the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century, the Batavian Republic and the time of French hegemony, when a struggle raged between patriots (those in favour of the republic) and Orangists (those in favour of the prince). (collections Vrolik and Blok, 1924)