The scary thing with art school is:

- YES you do need to invest soul money in it!

- YES you do need to strip mentally naked and bare your innermost soul for ALL to see!

- YES you will get critique.

- YES you might find out that there are things that you thought were clear and definite for everyone

but… it is only clear and definite for YOU, and if you have the will to communicate with others (which is basically what art is all about) you will have to change your ways. Or accept that no one gets it. Or even worse, maybe they get it, but they don't give a shit.

SOOOO… just keep being open.

I have been going to art schools for 8 years (3 years in Sweden, Rietveld for 3 years, 2 years of Sandberg.) I remember in Sweden having this attitude that I was afraid that the teachers would influence me too much and that that which was unique in me would be ruined. I was making comic drawings and making music and I had this idea that I KNEW what I wanted to do; I didn't need no asshole teacher to tell me what to do.

At that time I was clearly not ready to go to art school.

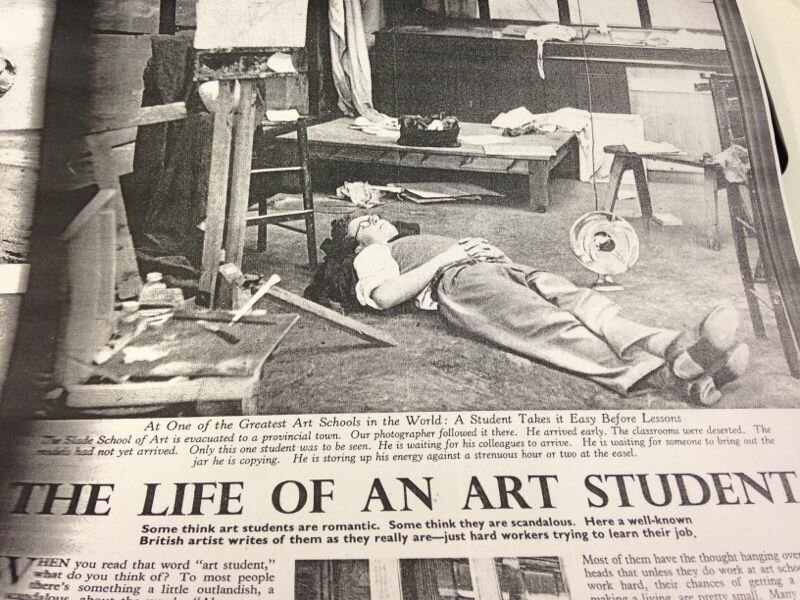

I COULDN'T receive, couldn't take IN, and wouldn’t let other people take part in my process. SO I stayed in a defensive mode. I basically didn't change much during art school in Sweden, just did my thing and was proud of it. After 3 years of art school I came out pretty much the same person/artist I was before.

After that I had a studio on my own for a year and did my thing. But when I was sitting there on my own I realized that SHIT, I just wasted 3 years of my life! I can ALWAYS do my own thing. You don't need to go to art school to do your own thing. You go to art school to get messed up in the head and to get new ideas that you would not come up with on your own.

After that, when I got a second chance at Rietveld, I decided to take that chance with open arms. Yes, I had assessments where I almost cried; I got so much shit from the teachers!

AFTER art school (I promise you this) you’re going to have the rest of you life to do ‘your own thing’. Like ALL of us (no matter if you are successful or not) you will be sitting in your dark studio somewhere in an industrial area or at home. AND you’re going to MISS those days when you had 20 people talking about your work and giving you shit and praise.

Good luck in trying to call 15 people to come over to your studio to see your art in five years from now. You'd be lucky to get ONE person to come over to see it.

So realize what a unique time this is, GRAB the art school experience with both hands and feet, tongue, brain and whatever else, otherwise you are just wasting your time, energy and money. USE us as teachers, use your fellow students. No one is here to hurt you, but we ARE here to give your ART shit (if needed) to make it bigger, better and stronger.

And the MOST important thing is your process:

- HOW you make art.

- HOW you talk about your art AND just as important, how you talk about OTHER people’s art.

- HOW you share your process with the rest of us.

- HOW you come to your results.

- HOW you present your ideas and work.

- HOW you make decisions.

- IF your process is open, transparent and inviting, then you are on the RIGHT track.

So, just let art school mess with you for a couple of years, it is not going to destroy you, it will make you stronger. And DON'T worry, that which is unique in you can NOT be hurt by information, assignments, other people’s ideas, or modes of working or talking. It ONLY gets stronger by more information!

And if after 5 years of Rietveld you think that all the stuff those teachers told you was just PURE bullshit, well, after that you will be stronger and more knowledgeable. Then at least you will know what you DON'T believe. And that is a MUCH stronger position than to NOT know that.

So in that sense you are in a win-win position.

AND if you then think, shit, this gets VERY personal and intimate very fast, well, the art world out there is EVEN more hard, lonely and ruthless. So this is like a safe haven where we can ALL experiment and be insecure together.

Including me…

I also don't have the answers; I am also nervous and scared. I have a big show coming up in Frankfurt in December and I am scared SHITLESS!!! I want it to be NOT good but GREAT, because I’m exhibiting with artists that are world class! So the nervousness starts to creep in: who the HELL do you think you are Jonas, exhibiting together with Jim Shaw and Jeremy Deller? Who the FUCK is Jonas Ohlsson??!!!! The only thing you can do is the get USED to being nervous and scared, and to try and suck energy out of that feeling, and to let that fear help you to make the best work you have ever come up with in your life.

If you are NOT nervous and scared, then you are not investing enough soul capitol into your art.

You can, of course, also be nervous because you feel that you haven't DONE enough, but that is the

WRONG kind of nervousness. You should work your ass off and STILL feel nervous, that's the right kind of nervousness.

Maybe you sometimes feel that SHIT, I am tired of being in this vulnerable situation as a "student"; I want to be all knowing, self-assured and arrogant! Well, the fastest way to get there is to listen a lot, go see TONS of art shows, buy TONS of expensive art books (yes, buying expensive art books REALLY works as a way to increase your involvement), make a lot of art! Talk a lot about your art.

To EXPOSE your fears, doubts and insecurities is the fastest way OUT of unnecessary fear, doubt and insecurities. But you can't get to that level WITHOUT passing that stage. So just get it over with!!!

The longer you try to hold it out, the longer it will take you to get to the DESERVED position of an all knowing, self-assured, and arrogant brat.

Greetings, Jonas