photo Joris Landman

The mother takes father on a trip. Their daughter Georgina stays behind with the nannies that are going to take care of her. The mother sends her daughter a postcard every day.

'It's proof of her love and her absence. 'And every day we were apart wrote to her.' (The mother)

'I have come back to the family.' (The father.)

'The drinking stopped and so did the postcards.' (The daughter.)

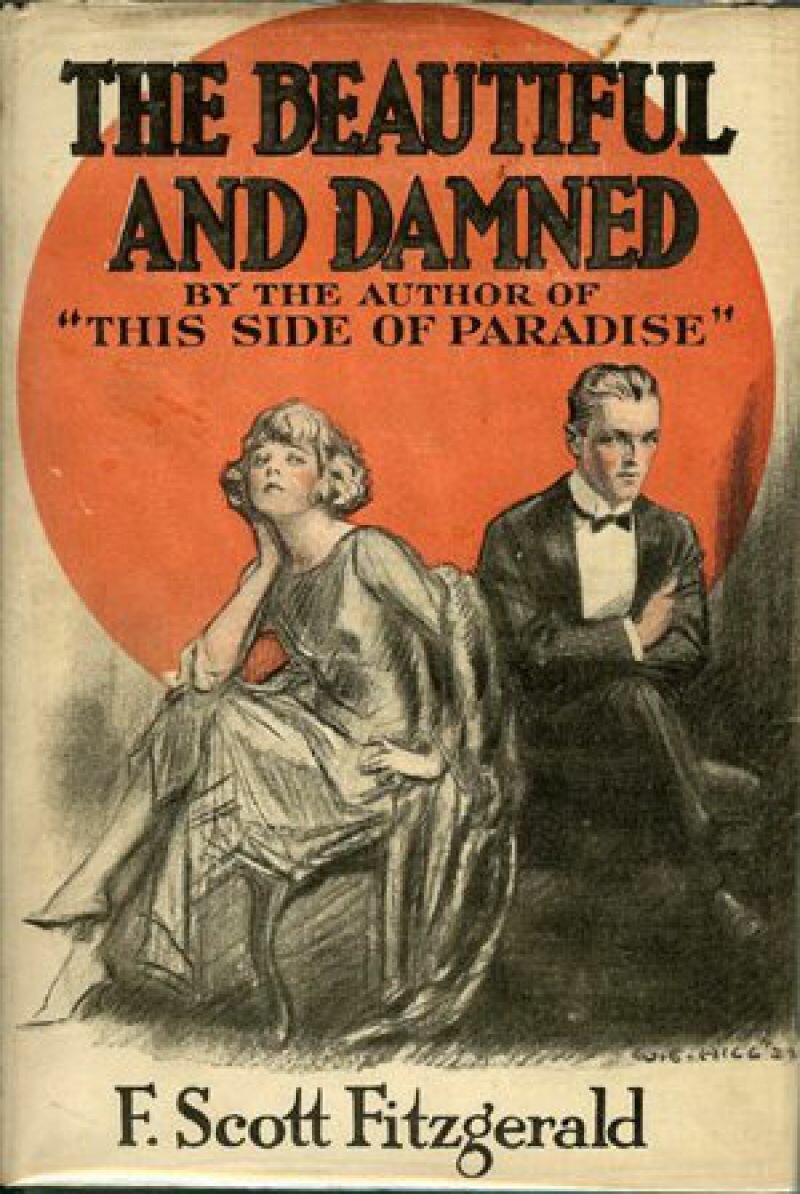

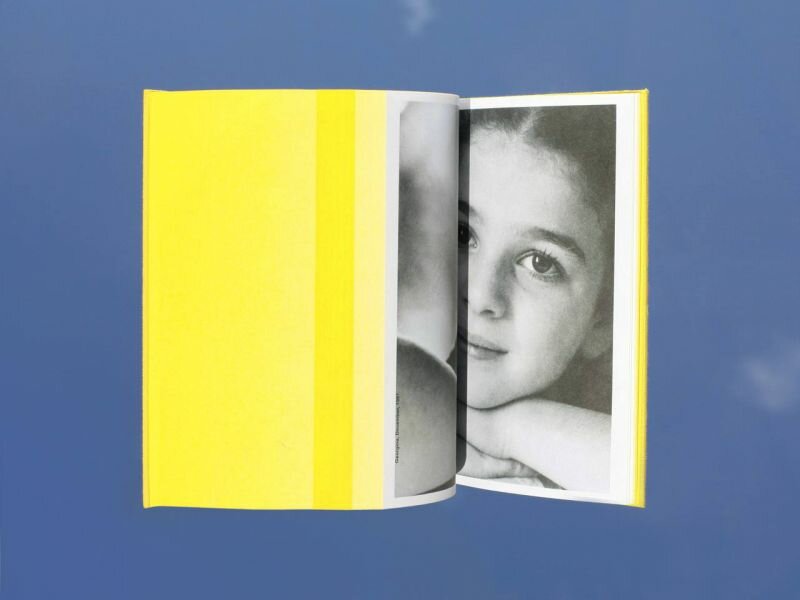

210 of the 1136 post cards were selected and printed in a thick book, the front and backsides matching and the written messages on the cards printed in block letters so that they're easier to read. A bright yellow, sun yellow book, thicker than a phone book, so thick the spine needs three folds to properly open. The book tells their story. The Beginning. This time over, James and Jennifer wanted to stay together.

Even when Georgina was born and the father kept on drinking heavily. The doctor warned him that he wouldn't have much more than two years left if he stuck to his drinking habits. Rehab didn't help. Jennifer discovered James hardly drank when they were travelling and decided to take as many trips together as possible, in an attempt 'to dry him out'.

The first trip begins October 25, 1989 and the card reads: 'Qui (we) love you more than Paris.' Georgina is 79 days old by then. On August 8, 1990, a day after Georgina's birthday, Jennifer writes: 'Over the Atlantic Ocean en route to Boston. My darling 1 year 1 day. The dots at the side the stamp are the spots of color used. I do wonder if you will like stamps. Mentioning dots reminds me of kites which are dots in the sky; a tug-of-war with the wind. Love Mumm.'

November 16 marks the last post card of that year, which means the family will spend Christmas and New Year's together. Thank God!

August 7, 1991: ‘We’re here and you’re there which is a terrible situation on the occasion. We have spent the day with Jill and that was jolly good. We laughed because we were with you on the 21st! These fellows threw the British out in 1775 just before the Boston Teaparty. Not like your birthday, a bit rougher. Love Dad and Mumm.’ The card has a picture of the statue of The Minute Man, lead gray against a bright blue sky.

How strange it feels to read the father's vile words towards the mother during this anti-alcohol journey: 'Mumm has swallowed so many pills that she rattles when she walks.' Other than that there are messages about the different kinds of champagnes, descriptions of celebrating Left Hand Day in the US, delays and bad behaviour, and on March 17 there is a little drawing of a hunting daddy: 'We are very sad that you have measles and a high fever - all these awful childhood diseases one has to muddle through in growing up. The good news is that the tiles were laid today in your bedroom and the bath is in situ in your bathroom.'

Later: Daddy has been brilliant. His French is so good the natives want to claim him.' And later this lamentation: 'To be queen and live with such paintings.'

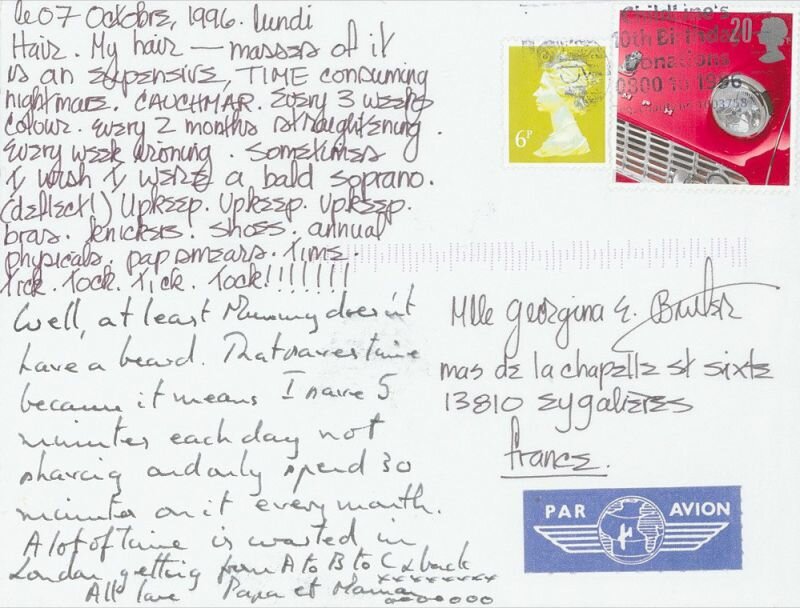

Except for a few, the cards aren't made for children, there is a lot of art, monuments, cities and landscapes. A sneak peek at the world. 'Hair. My hair - masses of it - is an expensive, time consuming nightmare. Cauchemar. Every three weeks colour. Every months straitening. Every week ironing.’

Some of the cards are made by hand and every stamp is picked with care, just like every written word has been carefully chosen. But it's not just the post cards that tell the story; just like every movie on DVD, it comes with extras.

The family turns itself inside out, like turning a piece of clothing and exposing all the seams, stitching and lining. What's this family doing to themselves? Each of three main characters shares stories throughout the book, there is a small photo album and there are the 'Conversations':

21 conversations they had, printed without any censorship. I imagine a shockingly honest AA-meeting and this time I get to participate from the sideline, I get to read whatever happens.

‘I don’t remember you and Dad at all before seven. Zilch (nothing). If we have 1200 postcards and some days there were three in one day, that’s a lot of years. And that’s being kind,’ the daughter says.

During ten years, 1136 cards were written. The daughter was left alone for about a third of the time. Jennifer kept all of the post cards: 205 flights, 268.162 miles in the car, two bull fights, one speeding ticket, 53 unpaid parking tickets, 13 cancelled flights, one bomb alert, 205 church visits, wars, inflating prices, births, funerals, holidays and so on.

Georgina remains mild and laconic about her childhood. At first the reader is confronted with a stinging kind of truth and the uncomfortable feeling that comes with it, but there's a sense of admiration at the same time. Georgina: ‘It’s been a much more honest family environment because you have never been dishonest with me. Dad doesn’t really say much so there’s no dishonesty there. [An ironic laugh] Yeah, I think a lot of families tried to hide things for so long – suddenly the truth comes out and all hell breaks loose. Our truth would come out and it would create very unpleasant moments, but it would only last a day or two days instead of three years because everything was hidden for so long. Life has been brutally honest from when I was young. That could have been good or bad but I think it’s turned out to be very good.’ And there are those truths every parents tells their children now and then, knowing the child will forgot about them is as soon as he or she turns around the corner. Parents try to calm themselves.

Daughter Georgina says in 'Conversations': On the other side was the lesson of the day: don’t ever be dependant financially. Rely on yourself first. Don’t marry a man with crummy shoes. A woman must never seem in a hurry.’

Jennifer made the book for Georgina's 21st birthday, but also for herself, as a kind of reassurance and oath at the same time. The book is dedicated to the eight children that came from their earlier marriages. Every decision regarding the book is based on the number 3, the price is 999 € and it's printed in an edition of 999 copies.

The immaculate design is done by Irma Boom. And no matter what you may think as an outsider, Georgina speaks very lovingly when it comes to her parents. ‘Even though my mother was absent, she immortalized every day she was gone. She endowed me with her ability to observe, give detail and discover a good story, and gave me a love for history and perhaps unconsciously, for Russia.’ ‘The book is yellow because it’s full of light and success!’ Jennifer says in an interview.