A Great Love

Nobody controls the intoxication of love that catches you off-guard like a terrorist, to tie you up and take you to sweet places. In this immersion, the ache of desire and total pleasure alternate. A great love might function as a tipping point, an experience that transforms the world for good. Across me sits Femmy Otten, in a conversation that is prompted by her recent installation (New Myth for New Family, 2011) at the Rijksacademie, in which love vibrated and triumphed, and the viewer was left feeling timid by the gazes surrounding him. Between us on the table lies the book by Pierre Klossowski, which is full of erotica and voyeurism. In Klossowski’s crayon drawings the classical merges with the temporary, and also the violent side of love can be recognized in the work; sometimes even literally, as in the photos in which he ties up his wife Denise.

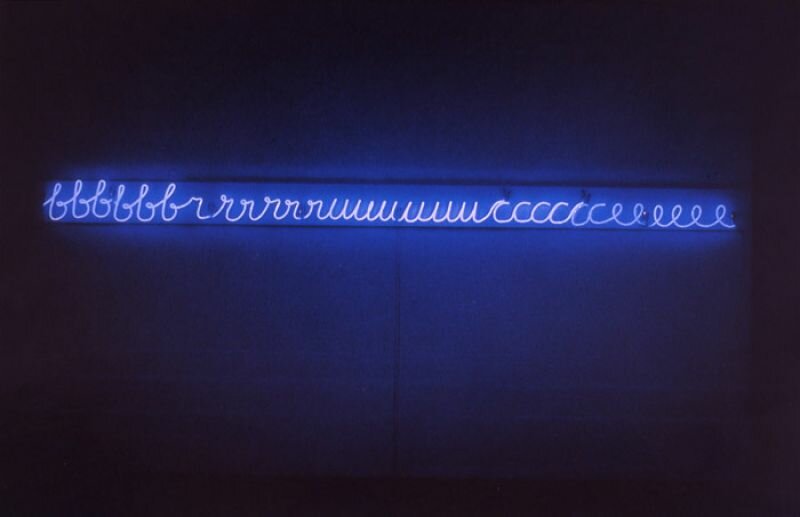

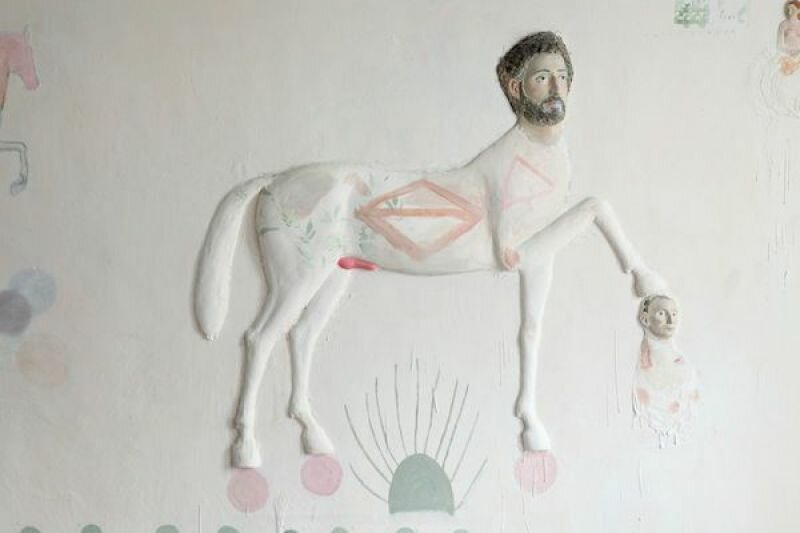

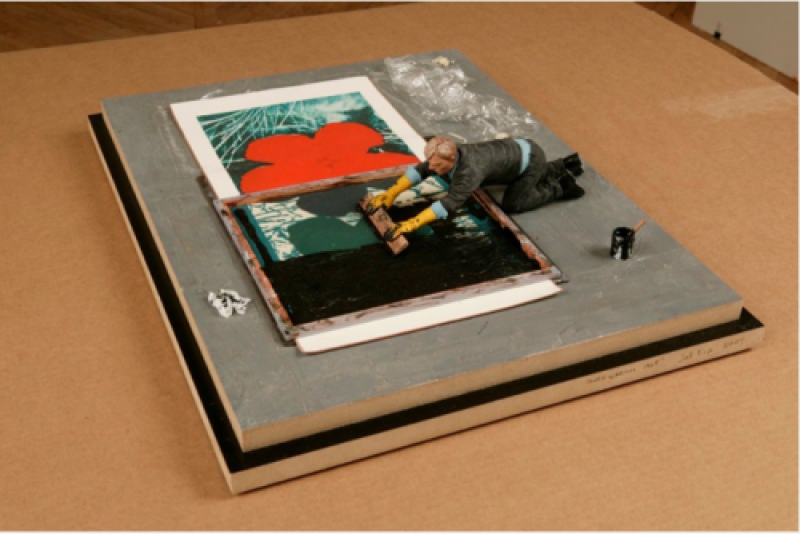

Otten relates the moment on which she first made, or could make, her first relief after a very intense experience of love. ‘After a stable and pleasant seven-year relationship, I got into an unprecedentedly intense romance. Something has since stuck with me and not gone away, whilst there was also something that had been destroyed. Not before did I know that one could desire so extremely. That surrender, real letting go, is what accompanied this love. To be able to free myself from it I have inscribed his story, as if he were the one writing it, I am him, and I made a sculptural relief about it. This allowed me to give the experience a place and move on. I have continued to use that switch of perspective: every time I make a work I write from the perspective of the person that the work is a reaction to. It gives me a strange kind of freedom.’

Somewhere in the book by Klossowski I encounter the line: ‘Then I married Denise very quickly. Denise represented reality while I was metaphysical.’ The reality of the body embraced his mind and took him along. That is what love does.

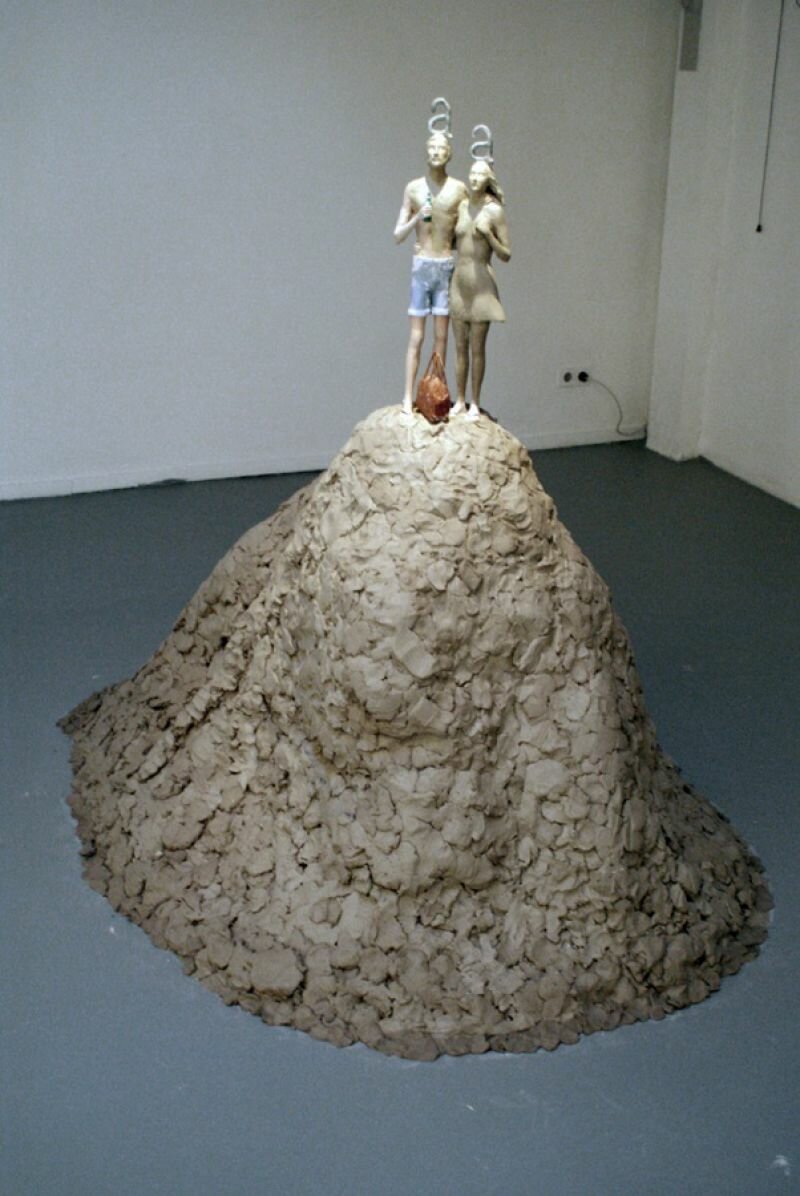

In the installation, a woman in low relief on the wall wears a medallion with the portrait of her beloved close to her. It is a realistic portrait, he even wears glasses. Above her head floats a halo in various light colours. Her cheek has been slightly grazed. Her body is squashed like in some strange flowered corset and her hands dangle clumsily downwards. Opposite the relief, the two lovers stand on a peak with earthly attributes such as a bag, blue trousers and a beer bottle. Two As.

‘I was so obsessed by love that I couldn’t not make a work a about it. But who possesses who, does he possess her amulet or the other way around? With the arrows and the halo, it is almost a sanctification of love. I have made his portrait, but I feel it is about all loves that I had to part from. While I am in the middle of love’s ecstasy, strangely enough it foreshadows the end.’

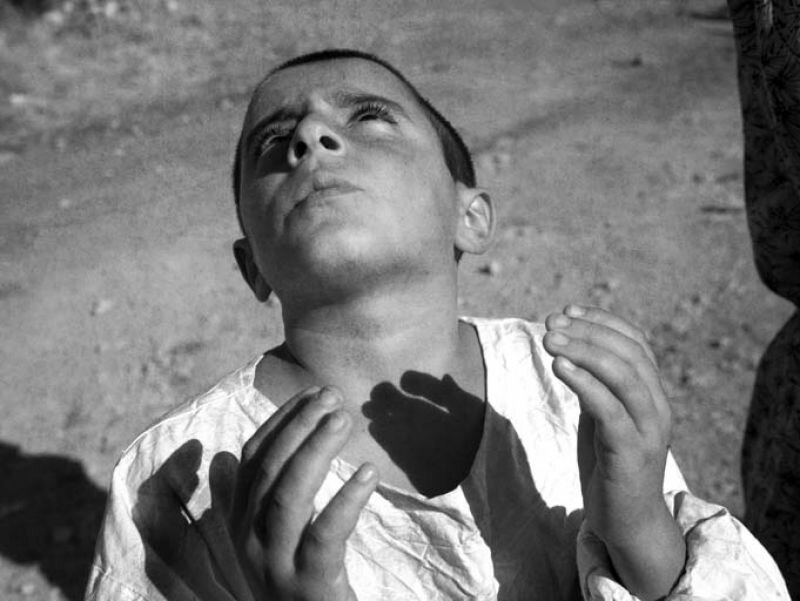

Klossowski speaks somewhere of a faltering moment, a wavering moment in which the jolting gestures give the impression of being possessed by unknown forces. The strange hands in Otten’s installation seem to contradict the directness of the facial expression, to push something away, a helplessness. Or the facial expression confirms that which the hands reject, renounce or deny.

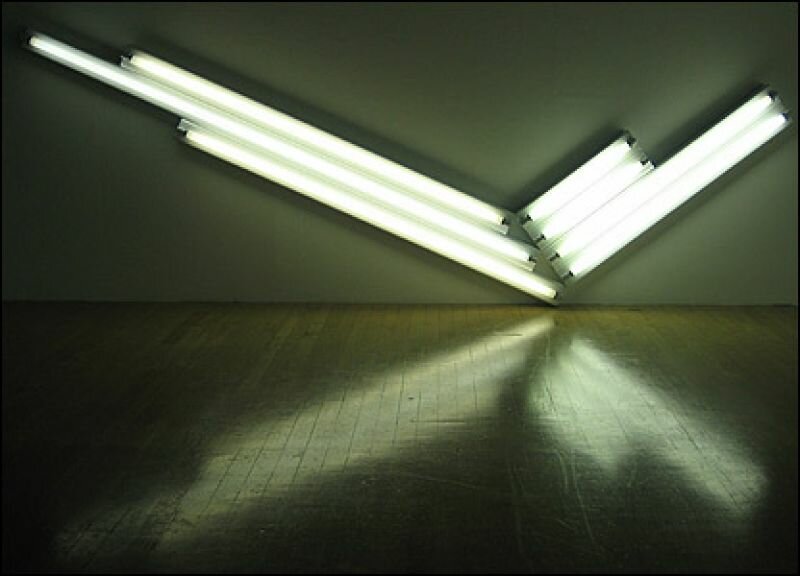

A former writer, Klossowksi spoke of his drawings as ‘the art of the deaf and dumb who are painters’. Standing in Otten’s installation, this silence breezes around you. It is mainly the silence of her experiences that is present in this installation, which, as a viewer, you can touch with your fingers in the air. A condensed moment that gathers everything that leads up to it and prefigures the gaze of the viewer. The viewer is caught between the gazes, locked in and locked out.

Otten tells how in summer she made a bike trip with her boyfriend across Italy, as a religious pilgrimage past the murals of the Early Renaissance. How her loved one grew in beauty with the exercise, tanner, more muscular, and how she would find herself red and sweating, trying to follow him. Love survived. The frescos of Fra Angelico and Piero della Francesca were a honeysweet catalyst.

Otten: ‘The Madonna del Parto of Piero della Francesca, in the church in which his mother is buried, is free of sentiment, pure painting. So moving. When I saw a fresco of Fra Angelico I was reminded of Henry Darger. I recognized that level of detail very much, he works per square millimetre; a peculiar devotion speaks from it, an almost autistic passion. I relate to that, it is what I am always searching for, short moments in which you are sure it is just right, that things will work out in your work. A destined feeling. During the realisation of the work I am very slowly looking for that precise form. Total devotion, that is what it is about too. It has to do with oblivion, that enchantment that leaves you in a sort of hypnotised state. A frenzy in utter silence and concentration.’

The same sometimes occurs to me when I am listening to a concert. Once, during a Schubert piece, my body seemed to grow, my body members felt very long with large warm feet and hands on the far ends. When your body relates to you differently, it is intoxication too. You can also get that when you receive a very pleasant massage from someone, but it is much more intense when it surges up from within yourself, much grander.’

At the exhibition at Art Association Diepenheim I saw her adding the final touches to a relief; she put on headphones for isolation and in uttermost concentration she finished the painting with a few strokes of the brush. ‘Working is a great ecstasy. Unfortunately I cannot reach it every time; sometimes I idle all day in my studio in order to work for a mere twenty minutes around eleven. I then need the whole day to do that. That makes it very frustrating sometimes, and it makes art a time-consuming affair. I can speed up the process just by drawing or making something, which will set things going, and yes, it then becomes meditative.’

‘Francis Alÿs finds this rush in hiking, in its repetitiveness. The rhythm of the footsteps makes you part of a larger whole. Everyone has his own rituals to reach a state of ecstasy.’

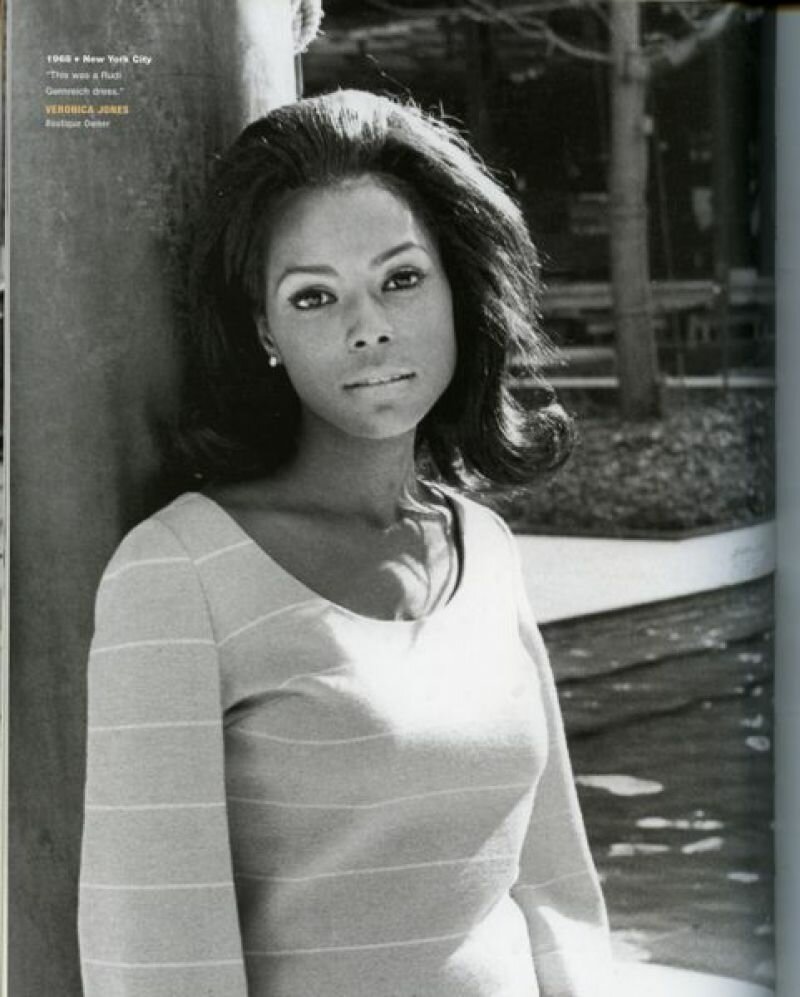

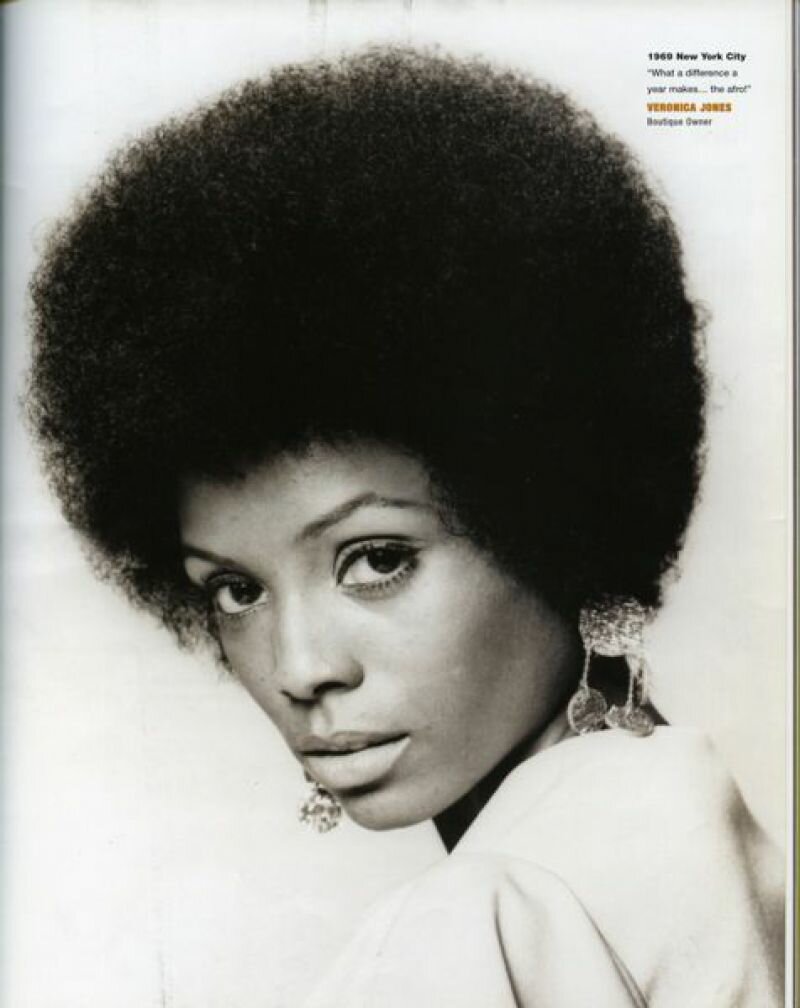

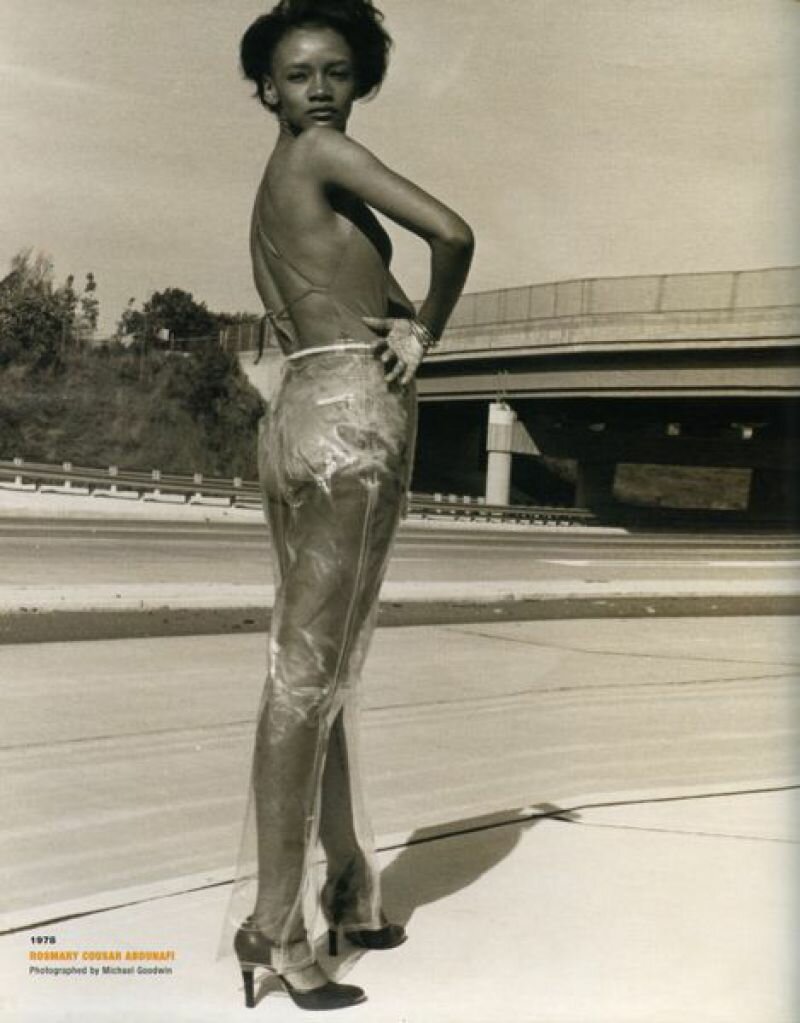

‘It is a specific beauty that has its hold on me. I can’t quite put my finger on it but it makes me very happy. It might happen just on the train, when a young girl obsesses me with her beauty; I enjoy that, it is most exciting, the adventure of looking. I want to hold onto that so badly. The feeling that something can disappear so easily is hard for me to bear.’

‘My work is always about the ones close to me, but also there do I have that very specific feeling of beauty. I often use the face of my youngest sister because she has that specific, magical beauty that I’m looking for. It has always been very clear what I found beautiful, the archaic, the simple, powerful shapes, free from emotion. But it is more than that, it is also something primordial, something ancient, that tells no story but is visual, a sublimation.’

As a 13-year old, Femmy and her mother walked into the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. She saw the charioteer of Delphi and started to weep. A museum guard took her by the hand and she was allowed to climb the partition and stroke his foot. ‘To touch that statue seemed an almost sexual experience, so strong and all-encompassing.’ The charioteer, originating from the sanctuary of Apollo in Delphi (470 BC) is a stately bronze sculpture of 1 metre 80 tall. A tall man whose heavy tunic falls down in folds. An open glance, set in coloured eyes, a slightly open mouth. An experience that already started to tilt the world.