Catedral de la Almuneda. It was in this church that I first came across ex-votos without knowing what I was looking at. Fascinated, I stared at a wall where dozens of beige coloured shapes were hung. Forms made of paraffin wax that seemed like they’d been moulded straight from a human body. I could discern eyes, a liver, a heart, limbs, breasts. I took a few photographs.

When I looked back at the photos, I realised this was the first time I’d ever witnessed such an exceptional presentation of blind faith. A faith in a higher power that could protect, heal, and that one could show thanks to. That is if you, as a faithful believer, were given the opportunity to hang an object of the sort on the great wall of the church.

Upon my return to The Netherlands, I asked the curator of the Catherijne convenant in Utrecht what’d I’d seen in Spain. He told me they were ex-votos, which literally means: to offer out devotion. Ex-votos are usually small objects, sometimes casts, other times paintings, drawings, or photographs. But essentially, they can be anything, as long as the're offered with the immense faith that someone or something in the heavens above is peering down with compassion.

In the old days, the very rich could grant the church a candle as large as their weight in wax. As long as the candle burned, their existence was ensured.

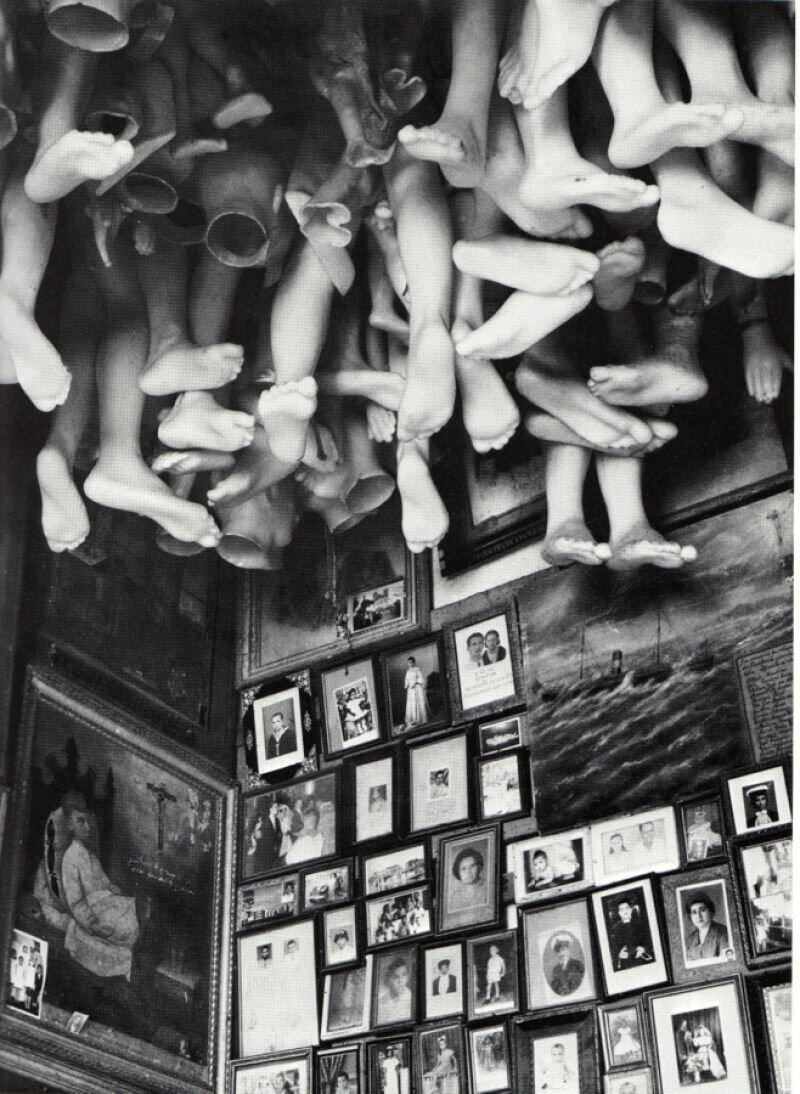

Years later, a friend and I took a trip through middle Europe in search of ex-votos. We came to chapels where we found hundreds of wooden legs stacked in piles by grateful believers who might have re-grown a leg, or had otherwise regained their powers of mobility.

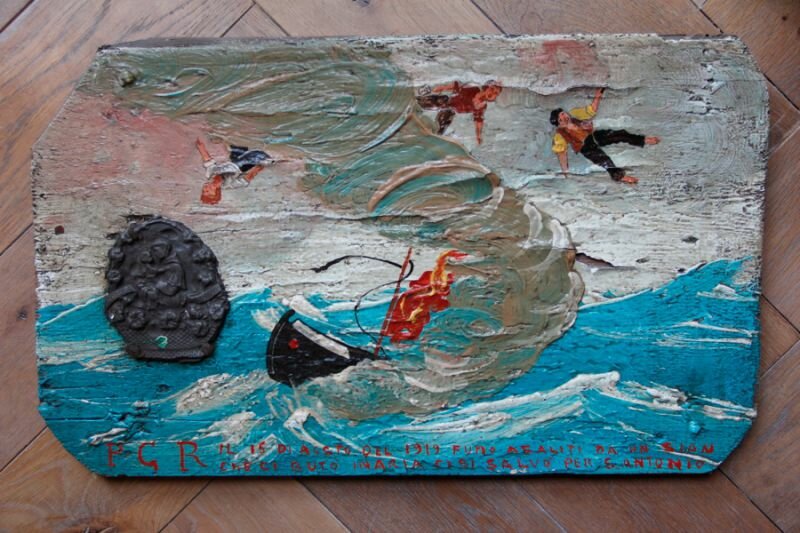

Unbelievably beautiful and naively painted images depicting the rescue of a loved one from a fire, or surviving a serious illness. Often in a corner of the painting there would be a saint who lovingly looks down upon the scene being carried out underneath him

This trip led to an artwork in the courthouse in Groningen. A place where worldly power prevails, but where truth is still verified by swearing on the bible. You never know. A place where the air of the visitor room is pregnant with a sense of justice, protection, and mercy. Where each object might possibly be used as evidence, which is precisely the opposite of faith: attempting to convince the believer without evidence.

Along the way I came across ex-votos everywhere. Sometimes they were needy: pleading letters in a Cuban church and at a place of pilgrimage in Wallonia. Others were placed out of gratitude, like the long row of motorcycle helmets or the altar filled with photos of car accidents at a church in Padua. Or photos of fishermen in a small chapel on the Flemish coast.

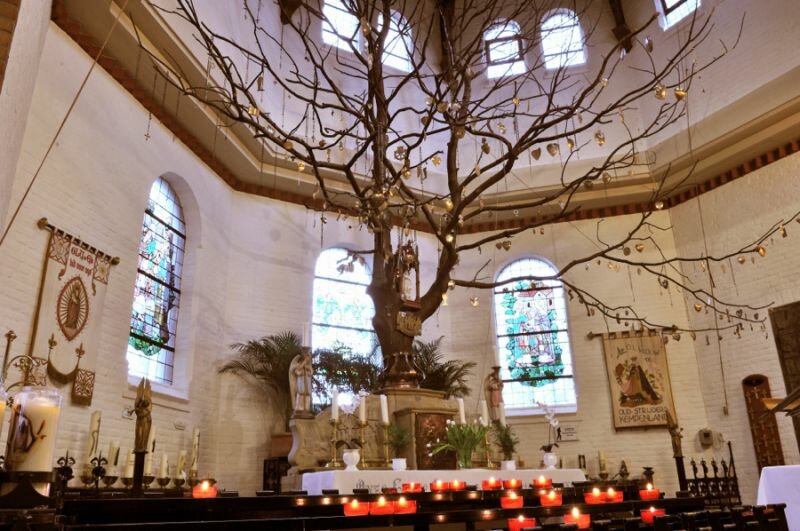

Even in The Netherlands, with its ceaseless religious wars, there are places where ex-votos can be found. Of course, the grand St. Jan’s Church in Den Bosch is one of them, where countless metal trinkets are hung, as well as the St. Bavo Church in Haarlem. Here, a number of exceptional, carefully crafted little ships hang motionless—no , they float motionless—under the great arches. They are a testament to the faith in a higher power that will keep the fishermen safe until homecoming.

We’re all familiar with the search for protection or the desire to express our gratitude to someone or something. All of us hope for a higher power, for someone or something to see us. Maybe each one of us has our own, private ex-voto, hidden away in a secret spot of devotion. And maybe it doesn’t matter who you thank or who it is that protects you. Maybe all that matters that this object exists, and that it's you that knows it's there.