The Internet encyclopaedia Wikipedia is one of the top six visited websites in The Netherlands. Interestingly, the content of this source of knowledge is contributed completely by unpaid volunteers and write the entries in their spare time. It’s curious, indeed, that this functions at all. In June 212, the Dutch Wikipedia will have existed fifteen years.

The Wikipedia entry on Wikipedia.

I use Wikipedia almost daily, and often compare entries in different language. It’s fun and informative, but I must admit I don’t write entries myself. Somehow this is a shame, because the best way to improve the encyclopaedia is to actively contribute. That’s the main principle of Wikipedia: two heads know more than one.

At the moment, most of the contributors to the Dutch Wikipedia are highly educated men of around thirty years old. Men and women above forty hardly contribute at all. The Dutch online encyclopaedia currently encompasses more than 600,000 articles. The English version is the largest, with more than 3,100,000 articles.

Artists often complain about inaccurate entries about them on Wikipedia. This is readily resolved; they can leave a remark on the discussion page of the article with a reference to the correct sources. Dutch celebrities who threaten lawsuit almost always decide against it when they realize how easily entries are corrected. Every so often information cannot be protected. For example, an actress was unable to take action when the encyclopaedia published her maiden name at her disapproval because the same information was readily available at countless other places online. On account of this, the information remained on the site.

Critics are still concerned about the way that Wikipedia operates. This is mostly in regards to how neutral or reliable entries are.And, for example, what mechanism of control monitors Wikipedia when basically anyone with “good intentions” can participate? But the facts belie this suspicion. A study by scientific journal Nature in 2005 showed that Encyclopaedia Britannica was only slightly better than the English Wikipedia. And in the past five years, Wikipedia has grown and improved so extensively that one wonders who would be best now.

“Critical Point of View,” a Wikipedia conference, was held in the Public Library in Amsterdam in March, and took a critical look at the problems concerning Wikipedia. During these two days, international Wikipedia versions were examined, and their advantages and disadvantages were discussed at large. The Dutch Wikipedia includes a page where the disadvantages are described point by point. Like: “the majority is not always correct”, and “idiotic and purposely wrongful entries are easily taken seriously”. Wikipedia cannot guarantee the accuracy and quality of information. It’s admitted that, because of the project’s open character, vandalism is a problem here and there.

Like many before them, American conceptual artists Scott Kildall and Nathaniel Stern have experimented with the encyclopaedia. They created Wikipedia Art, an article created as an art work/performance that anyone could edit. But because this concerned a conventional page in the English Wikipedia, the page was soon removed. The artists argued that the page should be kept because references to this “art work” could be found in credible sources: interview, blogs, and texts by media-institutions. The argument used to remove the entry was that it consisted of information not suitable for an encyclopaedia. The action seems to be a futile attempt at using the encyclopaedia as an “art platform.” The debate around the project can be re-read on wikipediaart.org.

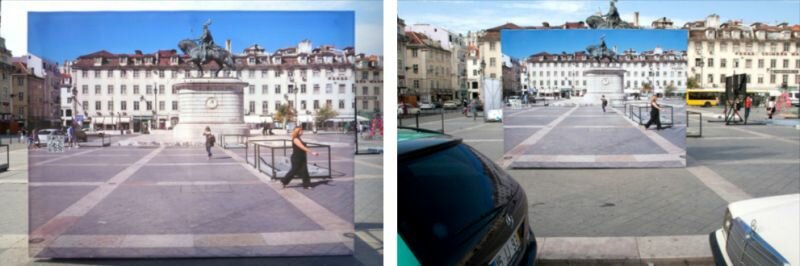

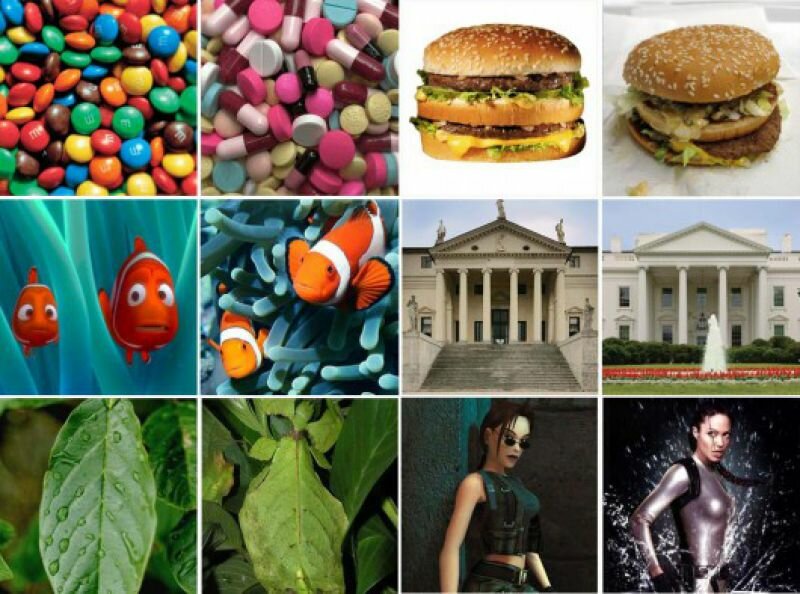

The photography competition Wiki Loves Art/NL is an example of another Wikiart project, initiated by Wikimedia Nederland. Last June, visitors participating in the project were asked to take pictures of art works in different museums – something that normally would not be allowed. Around 5000 photographs were uploaded to the website Flickr, and made accessible to Wikipedia under a creative commons license.Among the winning photographs was a photo of a lamp by Gispen, the brushstrokes on a painting by Isaac Israëls, and a vacation home by Rietveld. While browsing through the website's amateur photographs, it's striking how unalike the same work can appear in different lighting, or even by simply taking the picture from a different angle. Graphic designer Hendrik-Jan Grievink also noticed this.Previously, he had designed the memory game Fake for Real, in which two cards slightly differ from one another: one is "real" and the other is "fake".An image of a real clownfish is juxtaposed against an image of Little Nemo from the Disney animation, for example. Currently, Grievink is busy making an art book, Wiki Loves Art, and searches for the amateur's diverse perspectives: paintings are photographed with or without their frames, are very pixelated or extremely sharp. By playing with the many photographs from the amateur collection, Grievink not only documents these images, but also “re-mixes” them.

In 2006, the Royal Tropical Institute donated footage of our former colonies Surinam and Indonesia. These photographs were digitally "restored" by volunteers (edited so that the images would become clearer). Via Wikipedia, the Tropenmusem publishes information about the Surinam Marrons, descendants of the Africans who were forced to Surinam by slave traders.Also, volunteers translate captions into Bahasa Indonesian for the Indonesian Wikipedia. Institutes such as the Tropenmuseum benefit from Wikipedia's archiving of photographs. The material is used fanatically, improved by volunteers, and is provided with secondary information (metadata). This means that more people are being able to profit from the collection, which in turn increases its importance.

Of course, museums and archives publish their collection on their own website, but they lack the manpower and critical mass to improve the information. Also, digitalizing their collection doesn't necessarily increase visibility or reach a wide audience. By collaborating with Wikipedia, they’re easier to find through search engines, and they're able to reach a different target group. And, of course, an encyclopaedia remains an encyclopaedia; it's no online museum or archive.

For many museums, yielding control over their collections by donating footage under a free license is a great shift in thinking. The license naturally has some conditions, like referencing its source, but usually the material is also released commercially. Through using platforms such as the Internet, museums are developing new business models to place art and culture at the foreground. The first steps have been made in making available materials, made with public money, to the public domain. All of us are now able to use this material, which is good for creativity and, who knows, good for art.