If an idea to research something crazy suddenly befalls you, it’s well advised to go just through with it, complete it, and publish it. I once had the idea to visualise human coitus using an MRI scanner. It was a spontaneous idea; like the French poet-statesman Lamartine said, ‘I never think, my ideas think for me.’

I immediately received criticism. ‘What’s that good for?’ ‘You don’t even have a question! ‘We know everything already.’ But also enthusiasm: ‘if you want to research something that’s never been done, and easy as pie, do it! Why not?’

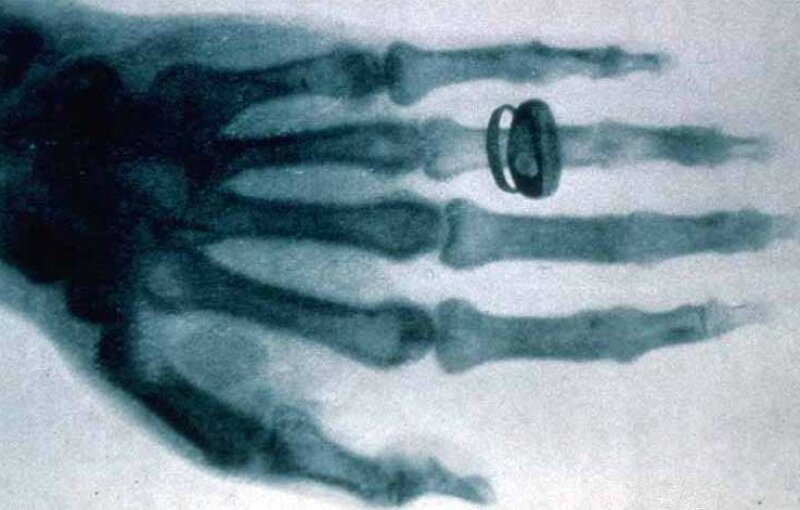

And so, we were able to conduct this study, but only in secret. Subsequently, the first scan was immediately compelling, iconoclastic even. It turned that all Da Vinci’s drawing proved to be fabrications, without anyone ever objecting (you and me included). The scans showed that the previous depictions had originated partly from the bedroom (before death) and partly from the cutting table (after death).

The article about our research was rejected three times. That’s just how deviant our findings from the scanner were. Even our fourth article was considered to be ‘made-up’ by the British Medical Journal. The article wasn’t considered an actual report of an actual study until the magazine had done a thorough research on the accuracy of it, without us knowing. They even asked to include us in their Christmas edition (where every year strange studies are bundled).

Meanwhile, the study is the most clicked article on their site, while images of the scans weren’t even on the cover of the magazine. The film version of the MRI scan on the ‘Improbable Research’ site has been watched over a million times. It also immediately received the LG Nobel prize, because it makes one laugh before it makes one think.

In retrospect, the study is a classic example of Spielerei nebenbei to Ernst im Spiel and freedom in research.

Like Johan Huizinga argued in his Homo Ludens: play is indeed a higher order than severity because play includes severity, whilst severity excludes play.