The calvary mountain in a bottle.

We all know that image of utmost intrigue of a boat in a bottle. How we delight ourselves in wondering how on earth one could fit the entire ship and its masts, sails, yards, booms, gaffs, bowsprit and rigging through the tiny mouth of a bottle! How very painstaking the task, how immensely disciplined the maker! Let alone the enormous amount of time spent making each separate object.

Although it may seem that way, ships aren’t the only things that have made their way to the bottle. In fact, the bottle is the scene for yet another setting.

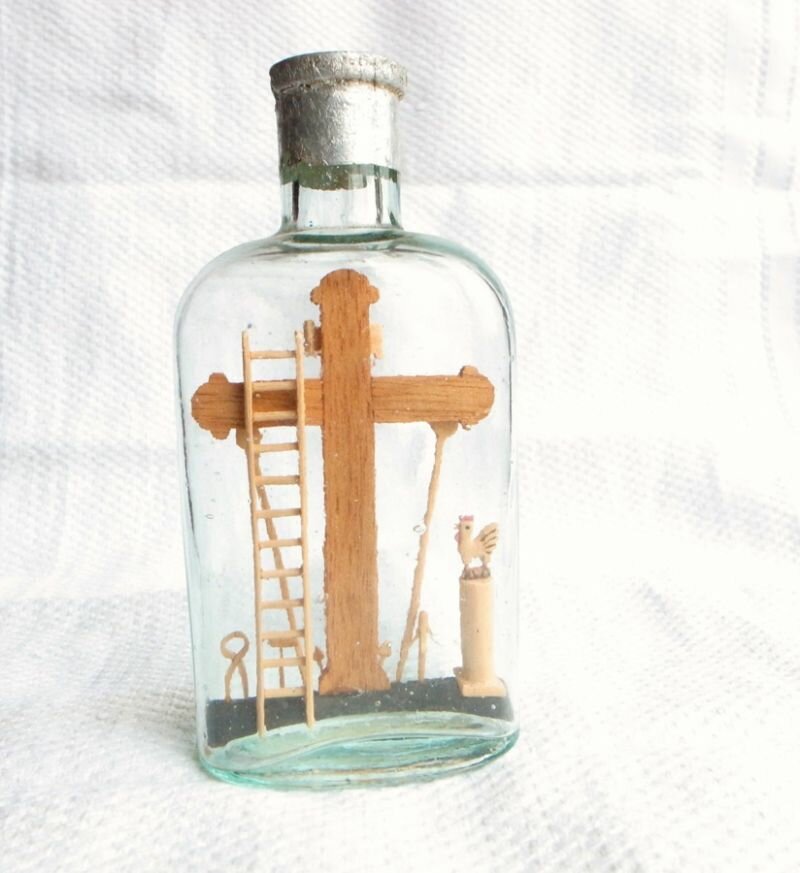

In the south of Germany and Austria, entire Golgothas are places inside bottles. Simple wooden carvings of the crucifixion of Christ, framed by Arma Christi, otherwise known as the Instruments of Passion.

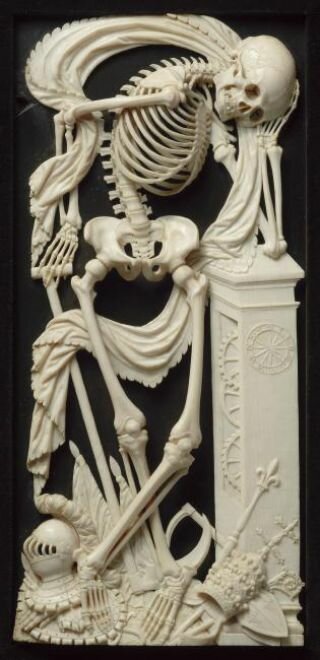

The word arma sounds related to weapons, and so it is. For the devoted, these symbols represent the weapons with which Jesus entered his conquest against death from which he emerged victorious.

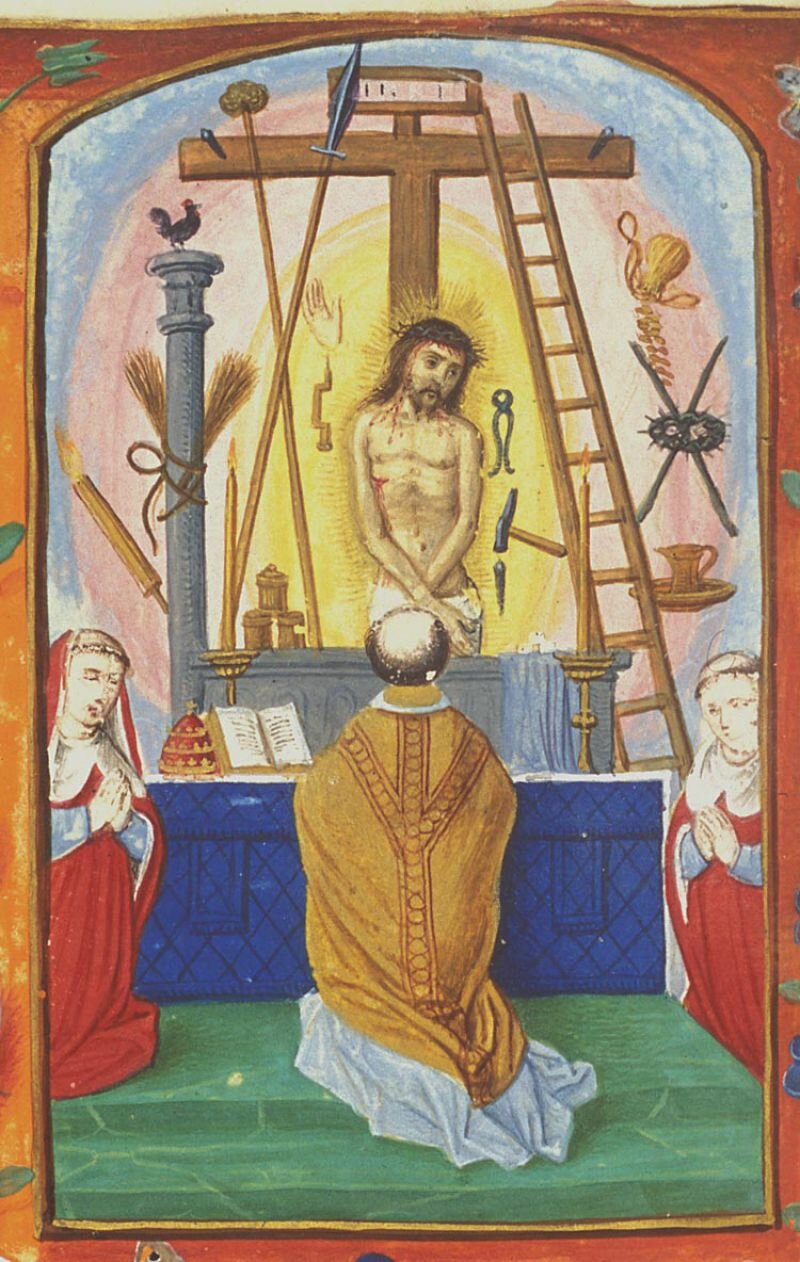

I’d previously only been familiar with the Instruments of Christ through an interesting painterly theme, namely, the Gregoriusmis. During a holy mass led by Pope Gregorius, Christ magically appeared as the Man of Sorrows. The Arma are scattered around him randomly and in and are painted in a cartoonish fashion on the canvas or panel. There are many instruments. The most important are the cross, the crown of thorns, the whipping post, the cock, nails, a hammer, pliers, dice, a ladder, a lance, a sponge (on a long stick,) but the more fanatic might proceed with the shroud of Veronica, the silver pieces Judas was paid (with or without pouch,) a spitting mouth, a portrait of Pilaus, a punishment tool made of knotted string, a bottle of balm, a king’s mantel, a torch, a Judas kiss, the good and the evil murder, a bucket (for vinegar,) INRI written on a piece of paper, the sun and the moon, a representation of the Denial of Peter, a pitcher and a bowl (in which Pilatus washes his hands of guilt,) a cup (that he can’t let past him,) and my favourite instrument: a sword stuck into an ear.

Using these symbols, one can reconstruct the entire story from Christ’s capture in the Mountain of Olives to his crucifixion and subsequent descent from the cross (which explains the presence of an object as mundane as a pair of pliers inside the bottle.) I’m well versed in the passion of Matthew and John. I even know them by heart, albeit in German.This is why: because I’m a professional classical singer, I’ve been singing Bach’s passions for four to three weeks a year since my college days. The passions are performed more in The Netherlands than anywhere else, whether this is St. John or St. Matthew’s version. At this point, it’s likely that I’ve performed the gospel dozens of times, and probably more than a hundred times per passion.

The simple wood carver unleashing his blades onto the blocks of wood in his wintry farmer’s home can find inspiration for the most precious details from St. John’s gospel. He tells us the name of the servant who’s short an ear after his meeting with Peter. He describes the garment that Jesus wears as he is dressed as a saint to be ““Ungenähet, von oben an gewürket, durch und durch.” These bottle of patience makers (“Geduldsflasche,) as they’re also referred to, don’t go as far. Besides the impossibility of really understanding what is meant with “gewürket, durch und durch,” most of these amateur carvers are not quite apt enough at their hobby to be able to go into too much detail with their bottle scenes.The dice might have the right amount of dots, and you won’t mistake the cock for just any old bird, but don’t expect any filigree wood works.

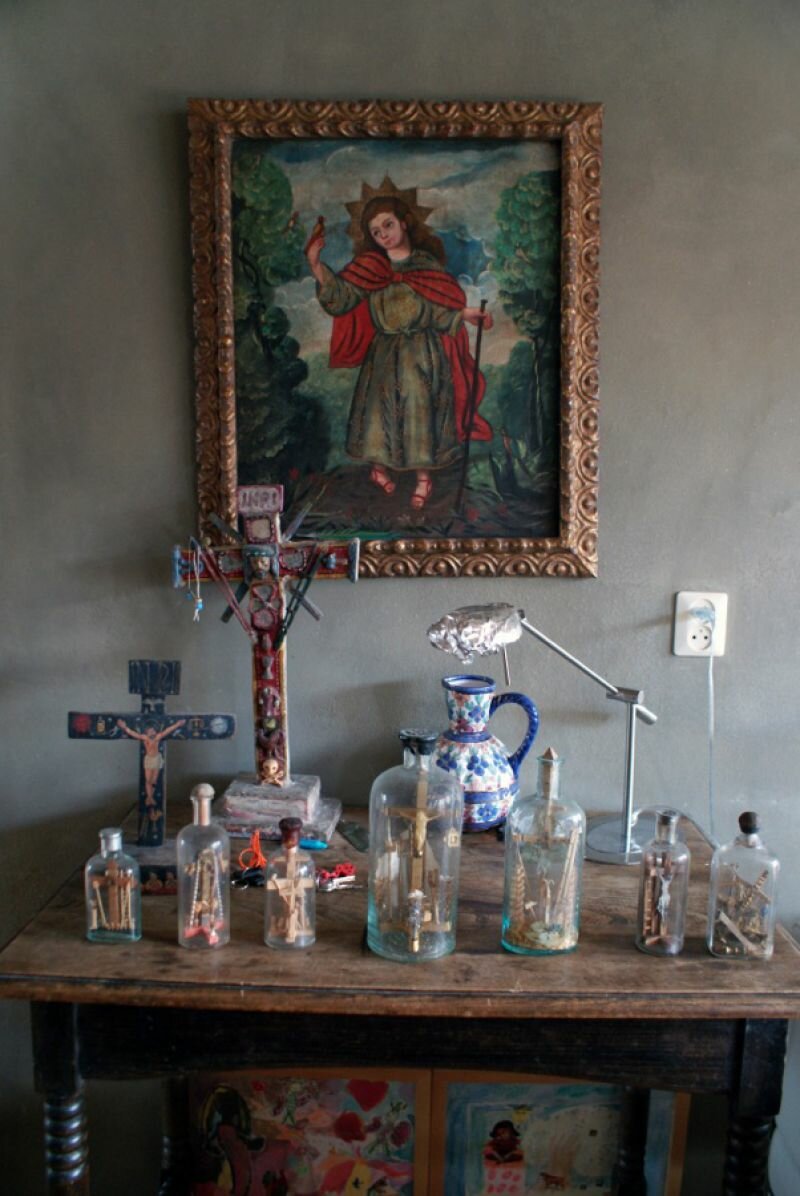

In the same areas where the crucifixion is placed within bottles, you’ll find the theme outside the bottle, in large format, hung up in houses. These are called Wetterkreuz, around which entire families would congregate on stormy days and nights when thunder and lightning would threaten the hay and straw decked farms, to pray for God to keep the house from being struck by lightning.

The Eingerichte that I own have all been bought on eBay and have been delivered to me by mail. The most beautiful example has not survived its journey intact. The goodnews is that now own one in which the earthquake (one of Bach’s Mattheus Passion’s most famous scenes) is shown. Now that’s rare.