“That which is creative, creates itself” – John Keats

Nothing remains unsaid at schools; everything is up for discussion. The child’s right to cherish his secrets is denied him. There doesn’t seem to be a place for daydreams, fantasies, or repression. Every minute of a child’s life must be meaningful. But children want to play and experiment without pretension. They should be allowed to form images and thoughts that manifest themselves within the hidden corners of the mind, far away and out of sight from others.

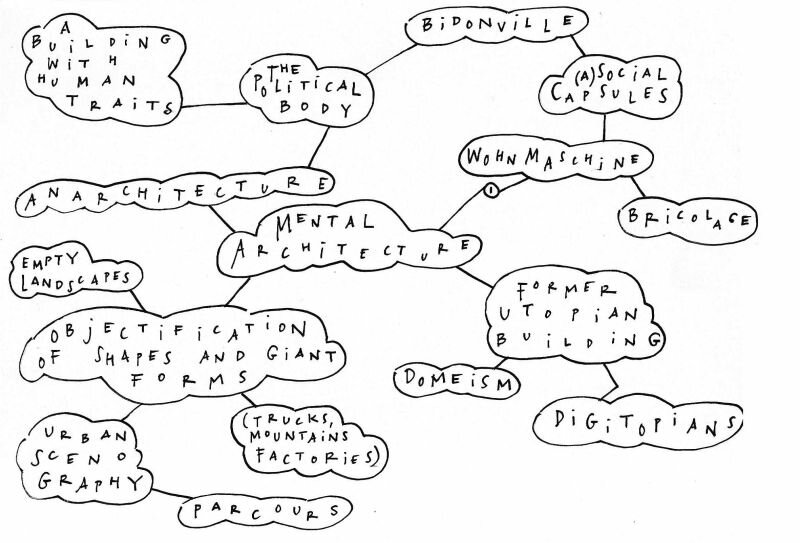

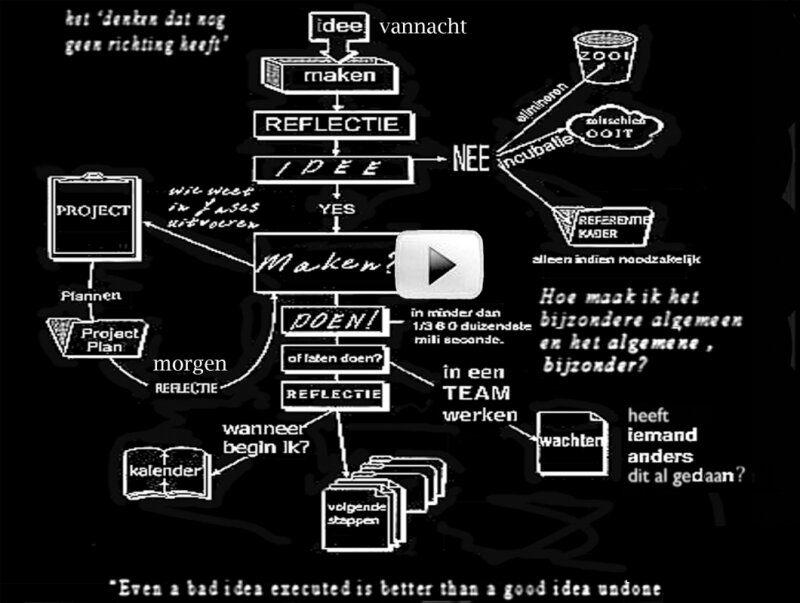

My life is given form by the countless images that impose themselves on me every three hundredth millisecond. The distance between the conscious and the unconscious seems minimal. Useless thoughts dominate my brain and link together to create a chain of countless, fleeting thoughts. Every action and all behaviour are preceded by fictional plans and fantastic imaginations.

My ability to make exceptional drawings was recognized early at kindergarten. Were parents and teachers competent to recognize ability? On the grounds of what criteria were my drawings assessed? When I analyse them, I notice realism, detail, and intensity. The sense of imagination is not strikingly idiosyncratic or expressive. The use of colours seems realistic. The images were related to trips and outings I’d made, as well as creatures like garden gnomes and fantastical animals. Goblins. The challenge was to portray these imaginary images as perfectly as possible. Kids don’t strive for expressiveness. Only adults appreciate the visible struggle of creation or the painter’s movements coagulated in paint upon the canvas.

My talent had little to do with the characteristics that would be important for a future artistic practice.

At primary school I endlessly drew mice with human features, top secret flying, driving, and diving survival cars; and even historical events made their appearance, like the beheading of van Oldebarneveld. Many artists say that they’ve felt like an outsider and an observer since childhood, and to have a greater sensitivity to their surroundings.

Teachers interpreted the bloody drawing as expressions of mental illness or family issues. By doing so, they made an implicit connection between artistic quality and mental abnormality. I had an undeniable urge to shock. Bloody, scary scenes lent themselves well for this. It isn’t only admiration that stimulates the need to create, a negative response likewise stimulates this need; I’ll show them! The feeling of being an outcast energised me.

When I was twelve, I had a teacher sporting a bow tie who presented himself as an artist. He created an inspiring environment by being a role model, observer, dreamer and rebel. The point of departure is what formed the student’s ideas, while constantly referring to art and artistry. He had faith in the idea of the student. It was this attitude that also drew students to him who had little to no interest in art. He was very conscientious, delayed his judgement and was constantly alert. The students believed in his honesty. Without being aware of it, he was a forerunner in what now would be called authentic teaching.

Still, I was seen as a talented student. That implies a promise that had simply to be fulfilled. At this point, heading to the academy seemed self-evident.

The promise remains. But the longer it stands, the less likely it is that it will be realized. As time goes by, personal identity becomes entwined with the identity of the artist. This makes quitting impossible. With Bourdieu in mind, being an artist is like a coat that I can’t take off, for if I do, I’d be naked.