We drive through the hilly woodlands of northern England. Our bus only just makes it through the winding roads to the entrance gate where we alight and walk up the hill through the wet grass into the cold evening. In the distance, a small structure stands in darkness. It’s Kurt Schwitters’ Merz Barn.

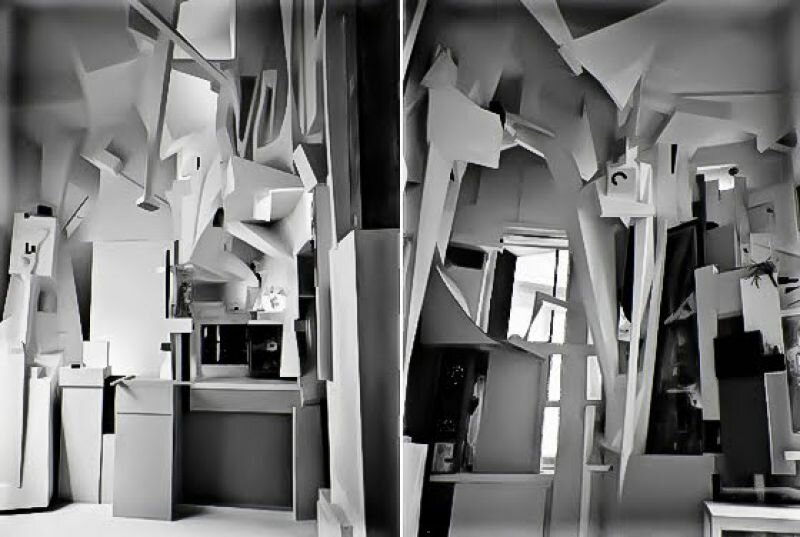

In the 1920s Schwitters began his Merzbau in Hannover by dramatically transforming the rooms in his house and studio into abstract grottos by manically covering walls, ceilings and floors with plaster, wire, wooden structures, paint, and strange objets trouvés. The Hannover Merzbau were completely destroyed by Allied bombs.

Hannover Merzbau

After being labelled an Entartete Kunstler (degenerate artist) by the Nazis, Schwitters fled Germany and landed in Norway where he built his second Merzbau, the ‘Haus am Bakken.’ This Merzbau, of which no photographs exist, was also destroyed within a decade of its construction.

Kurt Schwitters

We’re met by the live-in caretaker of the property, Ian Hunter, a greying man dressed in simple clothes. He shines a flashlight into the tiny dark empty barn where there’s little to be seen but a life sized photograph of where the wall used to stand. The original was moved; bricks, mortar, and all, to the museum in Newcastle after it had lain in neglect for decades. He tells us of how Schwitters denounced his German nationality, of his contribution to Modernist art, and mostly, of his love for the artist and his joy at owning the property where Schwitters once worked.

Merzbarn by day

Soup at the Hunter residence, 2013

Outside again, he shines his flashlight onto a grassy hill. That’s where he plans to build the Merz Shed, a structure to act as a gallery and education centre. Soon, a replica of the torn out wall should be erected where the original stood. He hopes a Kurt Schwitters museum will follow in a nearby town. 6 million pounds would suffice. As of now, there’s been no positive response from the funding bodies. Until then, Ian will remain living on the property and lovingly care for that little barn that carries the traces of Schwitters’ last Merzbau.

Kurt Schwitters in front of the Merz Barn in Cumbria, accompanied by fellow artist-in-exile Hilde Goldschmidt, 1947