Camouflage is a weapon that tricks the eyes of the opponent. Though it seems innocent, a life may depend on such visual deception. By way of a specific application of colour, patterning and shape, an animal or object merges into the background and/or is harder to recognise. This is of significance to both prey and predator, the latter of which is able in this way to sneak up to its target without being noticed.

Humans, however, have to get by with the colours of their bodies; fortunately they wield the human brain for a weapon, with its vast range of applications. This age-old technique of Mother Nature, the art of camouflage, was copied early on by monochrome men. Vegetius, in the 4th century A.C., mentions that the Romans painted their boats and the crew’s outfits venetian blue in order to blend into the background. The blue of this pigment matched the dark deep blue of the ocean they crossed to make for England, as ordered by Julius Ceasar.

During World War I, polychrome camouflage was applied at a large scale for the first time. In 1915 the French started to exuberantly paint their gear and armed vehicles. Up to then these had muddy colours to not stand out; now they were given separate colour fields according to the technique of shape-blurring colouring.

The first camouflage painters were members of postimpressionist and fauvist (less dots, more fields) schools in France. Later, modernist movements such as cubism had an impact on camouflaging armies, since they were knowledgeable of distored contours, colour theory and abstraction. In France one went as far as to found an official ‘Section de Camouflage’ in which painters worked. If you might have the idea that art does not dwell in times of war- well, it seems that art and war sometimes get along frightfully well. During the end of World War I thousands of ‘camoufleurs’ were employed in studios around Paris and thousands more at the front.

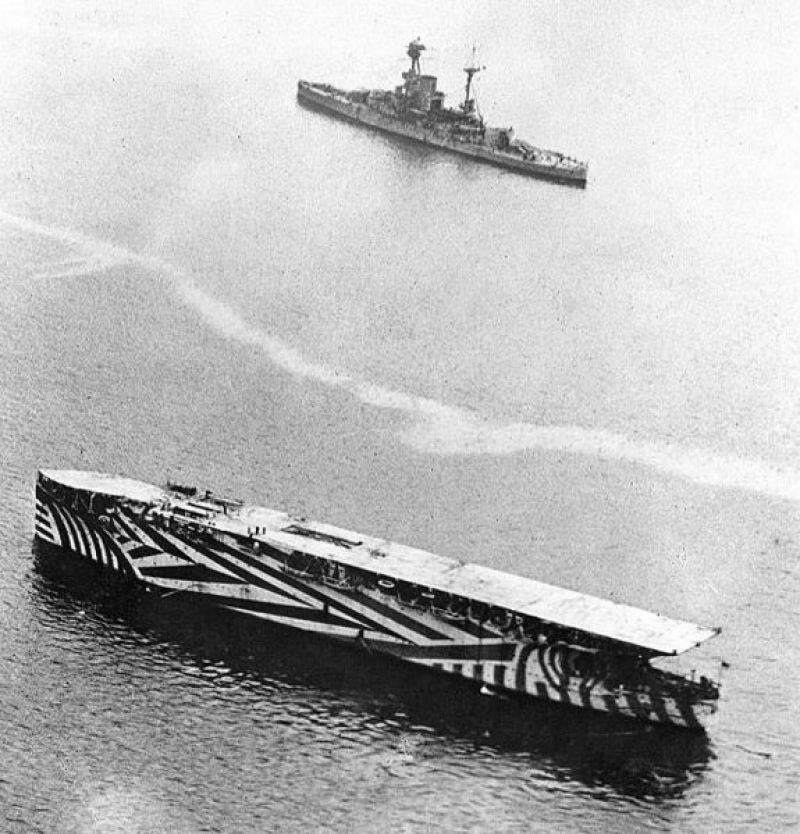

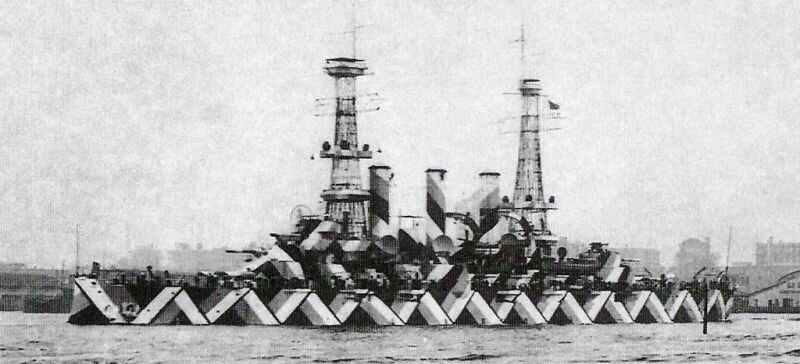

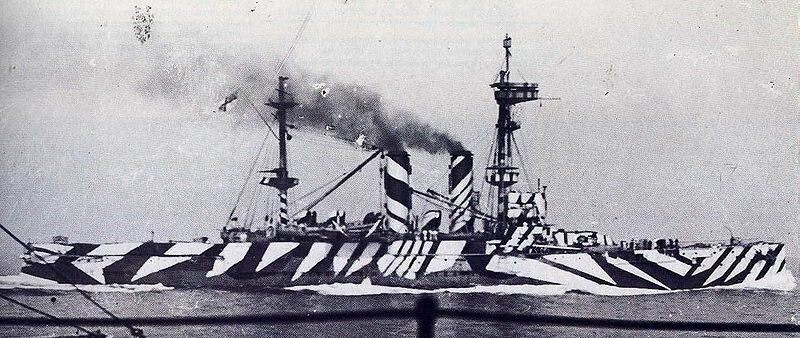

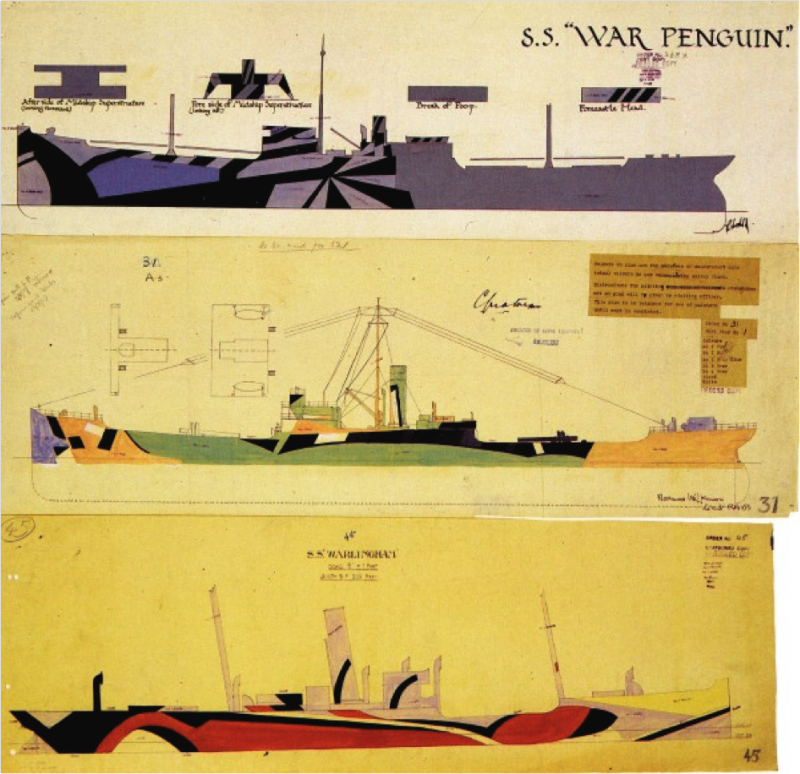

Cubism reached the flourishing peak of its military application when the cubists were commissioned to paint British and American ships. Neither the venetian blue the Romans used nor several other pigments appeared fit for the task of rendering the ships virtually invisible through the fluctuating weather conditions. Oddly enough, the colours needed to camouflage the ships were not to be found in the grey/blue spectrum, but in sharply contrasting colours such as white, black, blue, red etc.

Norman Wilkinson, a British marine officer and painter, conceived of painting the ship in geometrical fields with these colours, in such a way that the blurred shape of the ship would make it hard to gauge for the enemy, who would be blinded by the colours and miss when firing his torpedo. The effect of this paintjob was so significant that it became almost impossible to estimate the direction of the ‘razzle-dazzle’ ship. At the end of the war, no more ships were painted in this way. The aesthetics of the ships no longer fit with the military spirit and made ships visible for airplanes.