Every product in Euroland costs one euro. The countries that don’t carry the euro have similar stores like the Pound Store or the 99c Store where everything costs a pound or a dollar. While travelling through foreign lands, I’m always on the lookout for these stores. There’s always one. More than the touristic highlights, the cathedrals, or museums, I visit Euroland. I’ll easily skip a gallery, but I’ll never pass up a so-called junk store. Because although these stores are the same everywhere, they always carry different merchandise. Each country imports its own range of cheap crap.

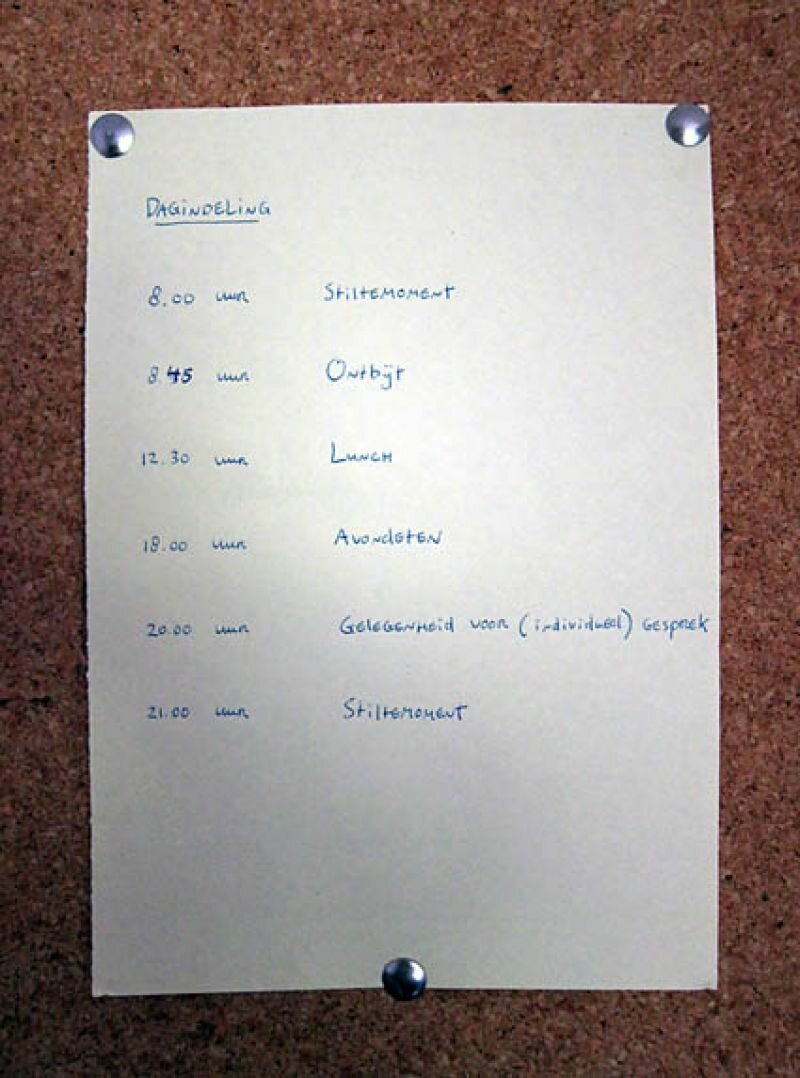

Photo by Dirk Vis

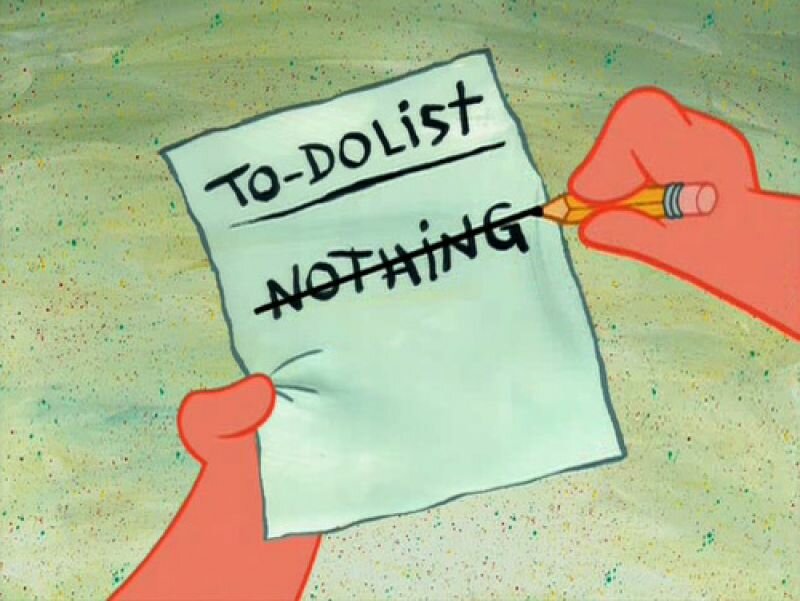

Many of the products have a second layer in addition to their direct function. A pistol is likewise a dolphin, a penholder also makes noise, a globe also serves as a stress ball, and so on. It’s this second layer that makes them so fascinating. And it’s the reason why, regardless of whether you use them, are special. As if that second layer is an excuse for their cheap appearance. I collect second layers. Their second layers bewilder, they’re silent witnesses of a world that could have been different. I like to imagine a world in which these strange products are the every day norm, where all pistols really are dolphins. And pink. Or where all penholders speak.

They’re sold in mass quantities. They’re made to earn money. For the makers, there is no ulterior goal (no urgency, no sanctity, etcetera.) These products are common objects without much consequence. In that sense, they’re the exact opposite of what economics terms the black swan: an unlikely occurrence with great consequence.

But just as in folk art and folklore, they find themselves relating to the mysterious directly and without pretension. They’re the least mysterious objects imaginable: stress ball, ruler, notebook; and yet it’s astonishing how strange they are. Why a stress ball in the shape of a globe? Accidentally, they often speak in beautiful terms. Like the butterfly that spins thanks to solar energy: the mechanics that drive the butterfly are bigger than the butterfly itself.

For a euro, you can own something that’s been envisioned, sketched, designed, assembled, shipped, packaged, and arranged. While they’re every day objects, they’re also completely absurd (a combination that could make the best absurdist jealous.) I often take one-euro objects home to use as artefacts in short stories. Without a doubt, they’re just as effective as inspiration for animations, design furniture, comic books, pieces of music; the list goes on.

Recently, I’ve been examining these objects ever more closely. With the advent of 3D printing, we’ll probably be able to print these objects ourselves in the near future. Of course, the euro shops won’t stop existing, but will their products remain as inventive, fantastical, and surprising? It’s for this reason that I collect them, a collection which is turning into a swan song for the euro products. Because it’s hard to imagine, and it surely isn’t a problem, but they eventually will disappear.