The Lustful Turk is a pre-Victorian erotic novel published in England in 1828, written in the form of a correspondence between the heroine, Emily Barlow, and her friend, Sylvia Carey. While sailing to India, Emily is kidnapped by Moorish pirates and is forced into the harem of Ali, dey of Algiers. Although initially resistant, Ali awakens her sexuality and she willingly indulges herself in sodomy, a great taboo in England of the time. When Ali tricks Emily’s pen pal, Sylvia, into coming to Algiers and entrapping her in his harem, a similar sexual awakening occurs. However, Slylvia refuses sodomy, resulting in her vicious dismembering of Ali’s penis. Emasculated, Ali sends the women back to England. Emily returns home carrying Ali’s amputated phallus with her, conserved in a jar of spirits.

The following text is taken from a conversation between the artist Patrizio di Massimo and Robert Leckie in October 2013:

I first came across The Lustful Turk while reading Edward Said’s Orientalism – a foundational work of postcolonial theory, as you know – during my MA at Slade School of Fine Art in 2009.

Edward Said makes reference to The Lustful Turk – a work of epistolary erotica published anonymously in England in 1828 – which he describes as a “black book” of Western Orientalism. Intrigued, I quickly bought a reprinted edition online. When first flicking through, I found it to be a very curious document. American academic Steven Marcus lucidly describes it as something like [paraphrasing] “a condensation of the stereotypes that the West produced about the Orient.” But its erotic, Oriental staging also fascinated me – you could say that I participated in the writer’s fascination. And I did this despite having originally encountered the book through Said, knowing therefore that it as deeply oriented in the ill-informed authority of Western “knowledge” about the Orient.

After discovering The Lustful Turk book, I questioned for a long while what form my engagement would take. I began roughly three years ago, while reading it, to do some drawings, which I never exhibited. I was in residence at the time at De Ateliers in Amsterdam and I remember trying to describe the project to some tutors and peers. My ideas then were admittedly very vague and while some of them found it a very intriguing prospect, others insisted that I shouldn’t pursue the subject and so I didn’t.

It wasn’t until some years later that I returned to the idea after receiving an invitation from Alessandro Rabottini to present a solo show at Villa Medici in Rome.

The path leading to that exhibition was rough and frustratingly slow. Looking back, I think I had three main difficulties: how not to banalise such a loaded subject, how to translate such an interpretation into painting, and how to “follow” the text, or not.

I think that reworking the cultural production of the past can encourage us to re-think what, where and how we have been before, culturally. And although The Lustful Turk may not be of interest to some, we all continue to be influenced by the way in which Western empires deformed the relationships between countries during the colonial period. The astonishingly simplistic and dichotomous relationships between East and West, so grotesquely portrayed in the book, are still politically relevant today and the fetishisaton of the Orient also persists. For the writer of The Lustful Turk the Orient was the place to imagine a series of sexual encounters that weren’t permitted in pre-Victorian England. For us, opening a space for debate about the representation of sexual desires and practices in the Arab world is I think crucial to our understanding of that culture.

When I started this project thought a lot about what position I should take. I could have, for instance, proceeded with moralistic judgement and political correctness, seeing the book as nothing more than an emblem of a retrograde and “racist”” culture, or otherwise I could have reiterated the author’s highly questionable motive, weaving my work into his, unquestioningly. But neither path felt like mine, and so I eventually realised that all I wanted was to somehow bring this topic to the table and do it in my own way.

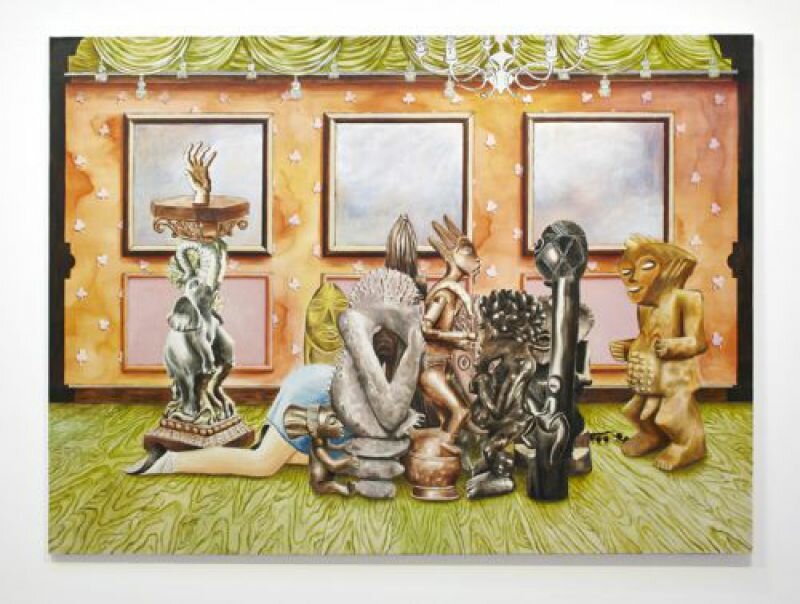

In this sense I don’t consider my project to be a replication or re-staging of the book – I see it more as a proposition regarding how entrenched we still are in our past cultural heritage. My referencing the book also serves primarily to emphasise the connection between the Orientalist tradition and sexual desire, which I believe remains an interesting lens through which to pick apart our relationship to the “Other” nowadays, no matter how problematic and ambiguous that relationship may be.

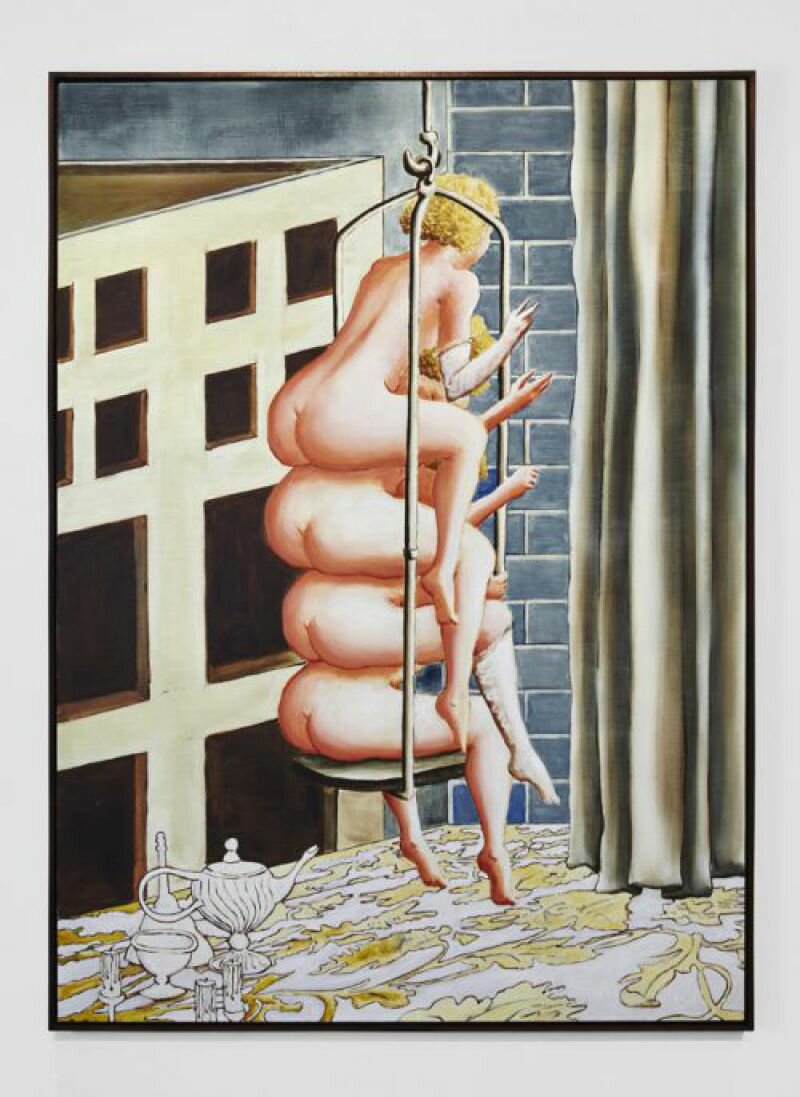

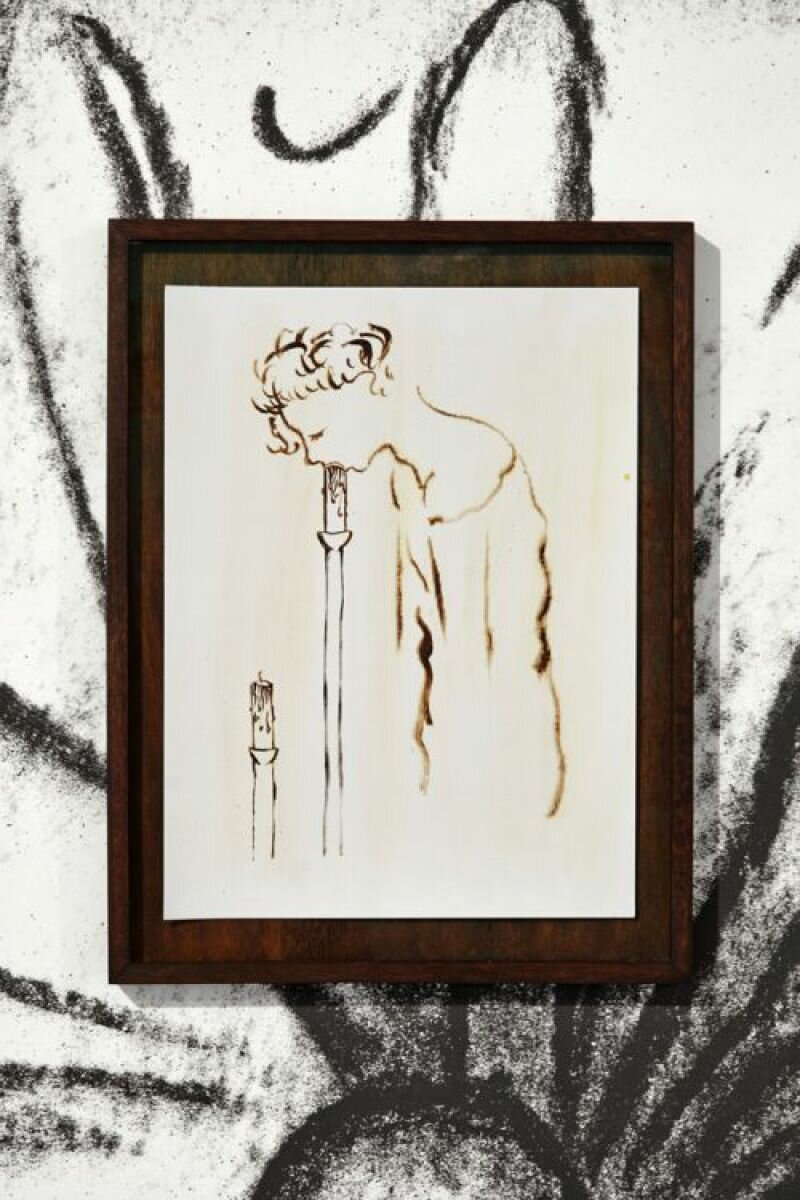

I didn’t want to detach the project from the illustrative tradition… I didn’t want my work to follow the narrative of the book page by page, with my images responding, secondarily, to particular passages of text. As far as I understand it, painting has always referred to literary sources historically, whether the bible or Greek myths, and my work looks for contemporary “ways in” to this kind of art-making. So that’s why I wanted to embrace illustration and to understand my work as continuing that tradition… These images are illustrative, but I also like to think that they can stand up on their own.

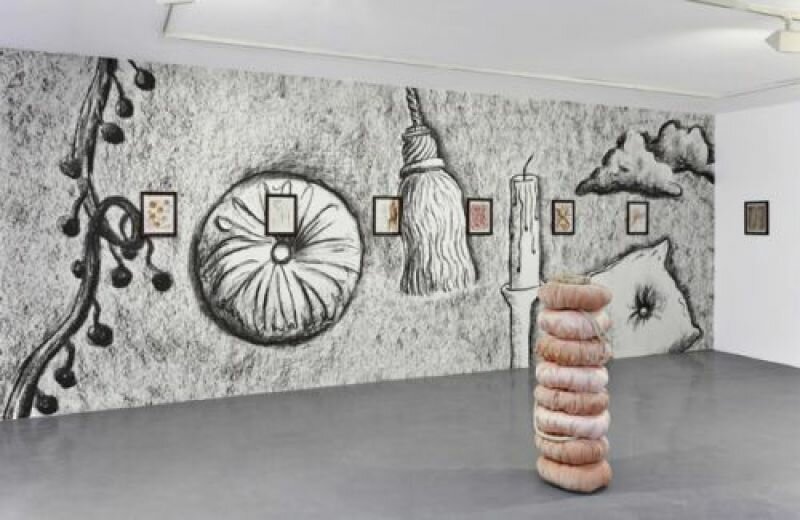

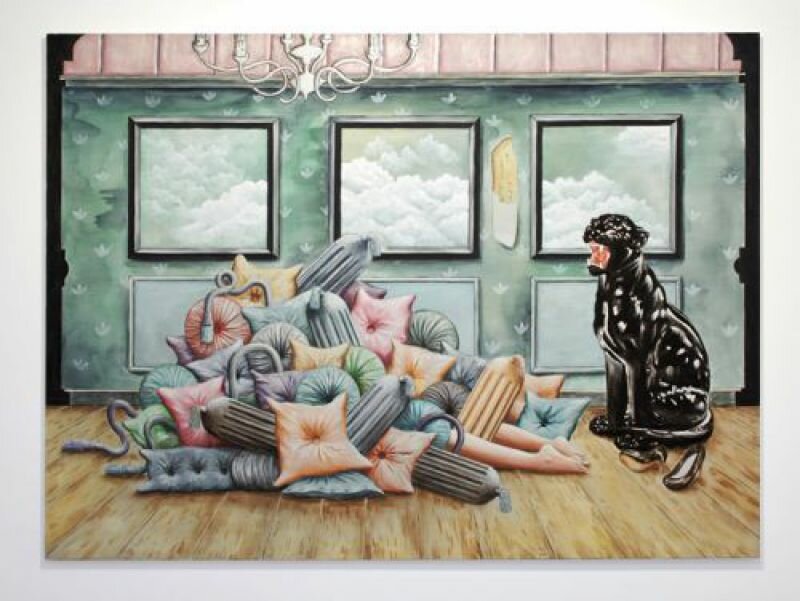

Imagining the harem interior, I became particularly interested in elements of décor – cushions, curtains, tassels, candelabra—in this way, I created a sort of meta-language. There is a reconnection with language through the use of visual “figures of speech”. In the same way that you can replace language with image, I found I could replace a leg with a tassel, for example, or buttocks with a cushion.

I also think these works are unapologetically over-the-top because I don’t think there is any reason to be apologetic. Racy as it may be, I have to follow through on my decision to make a project about this thorny subject, and I think, for me, that necessitates pleasure, playfulness and enjoyment. If The Lustful Turk book is based on stereotypes and how these stereotypes condition our understanding of an “Other” world, and if I don’t want to be moralistic about these stereotypes then I must make use of them.