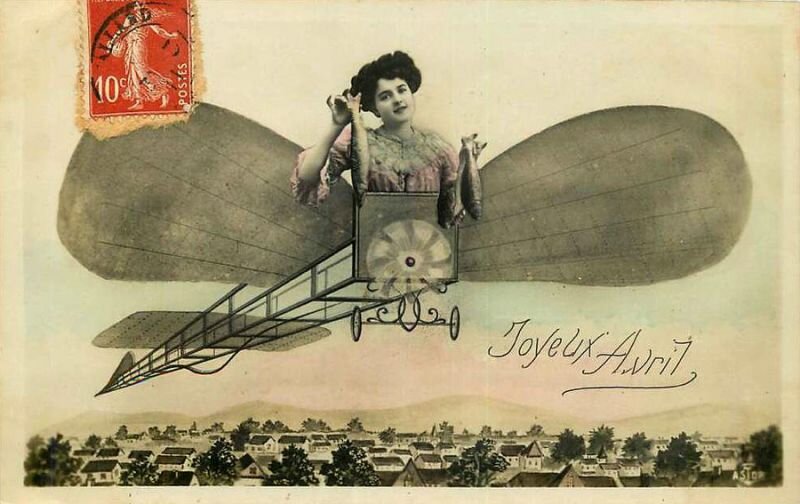

In a garage sale, a briefcase filled with photos and typed papers is found. All of them document a passionate affair, which took place between May 1969 and December 1970 in Germany. An affair. What a delicious word. With a strip of birth control tucked in the handbag and a new moral in mind, the sexual revolution was ready for take off. Premarital sex became more common and one might say that marriage even got abolished. Freedom lured all.

The book Open Marriage opened all doors en described how to respectfully let each other be. Married couples often organised swinging and key parties. When entering the party, the men threw their car keys in a big jar. After enjoying each others company and a glass of wine or sherry, all women took a pair of car keys and left with the man whom they belonged for a passionate night together. Of course, some cheating occurred (my key is the one with the peace mark).

An affair fascinates more than planned adultery, because it is about passion for the one man or women and filled with secrets. Because, revolution or not, the married did find it difficult to share their partner. With every infatuation, the choice of being straight forward occurs. And then there's the practical side… How do you organise an affair? How often can you get away with 'working late'? Always being cautious that not the slightest stain of pancake is still on the collar of your shirt. Covering tracks is necessary in an affair.

Chronik einer affäre. This archive of a secret affair goes against all code. Instead of covering his tracks, main character Günther documents his affair like a compulsive accountant, collecting evidence with photos and descriptions.

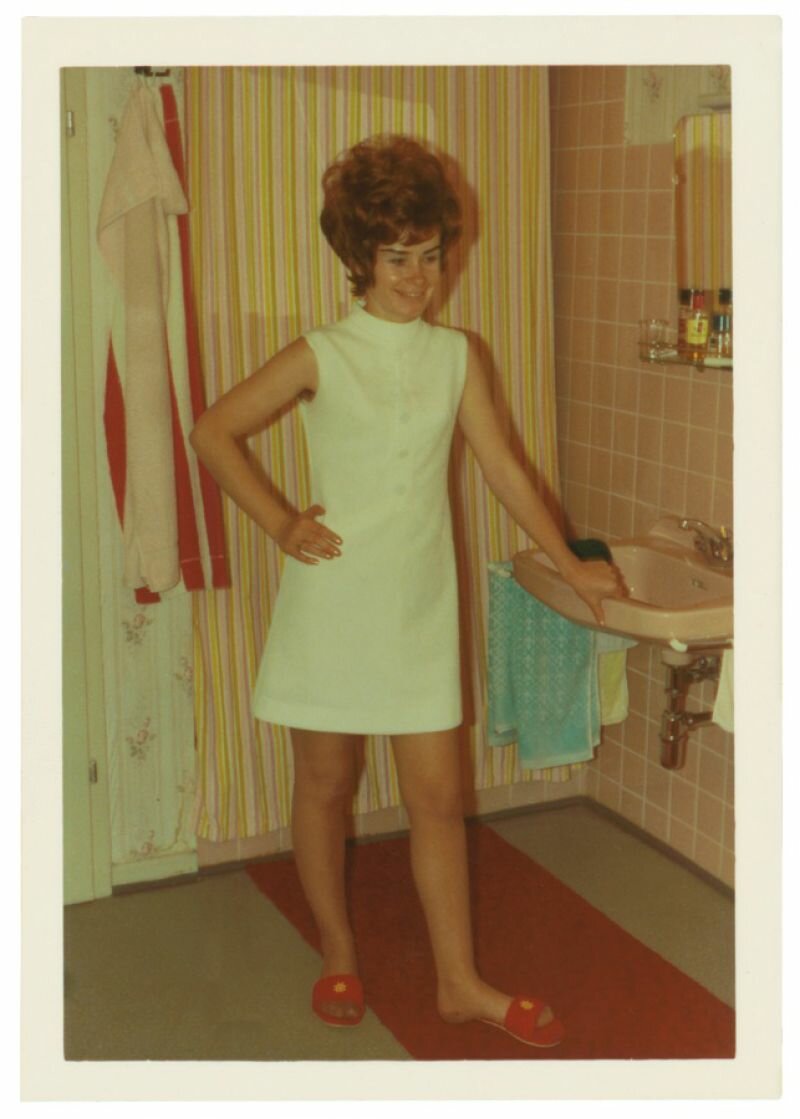

Günther is 39 years old, owner of a construction company and his mistress Marget is his 24 year old secretary. On the first black and white photographs of 11 May 1969, we see Margret at work on her typewriter. She looks into the camera, a little shy, wearing a light sweater with two pockets on her small breasts. Her eyebrows are straight lines, which bend up to her temples. Her hair is dark. Another picture showed her posing at the table with her skirt pulled up high.

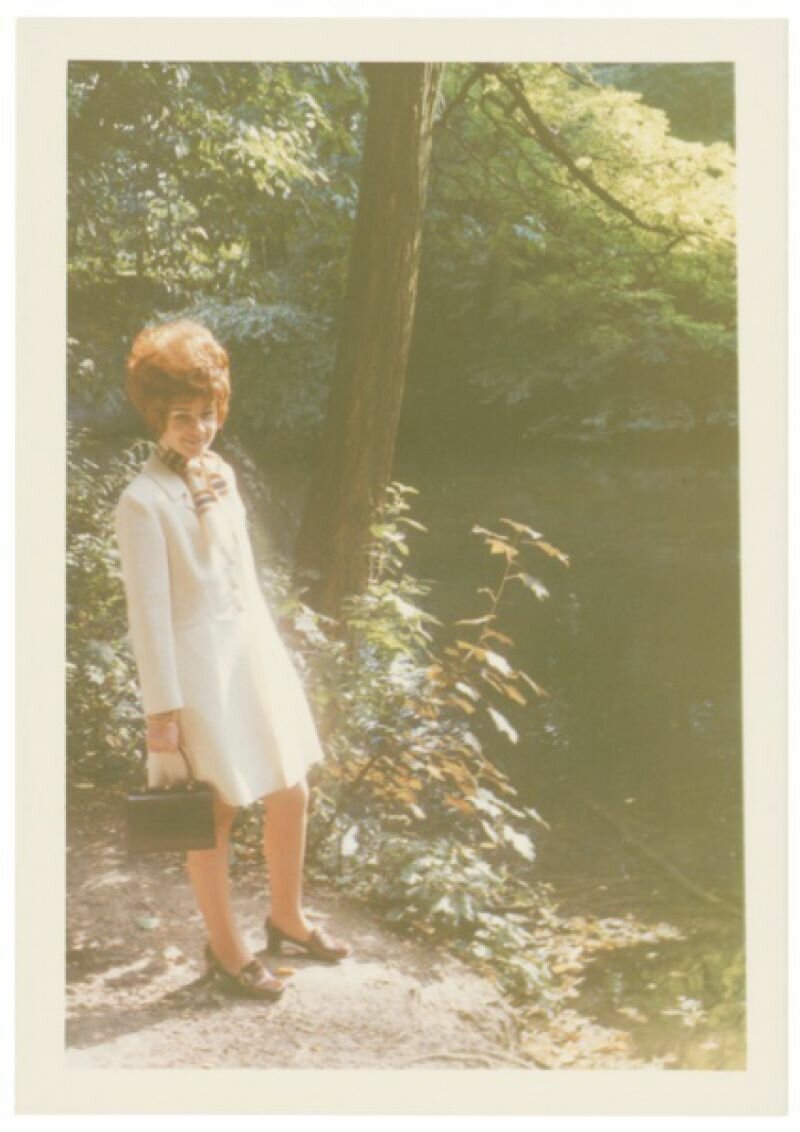

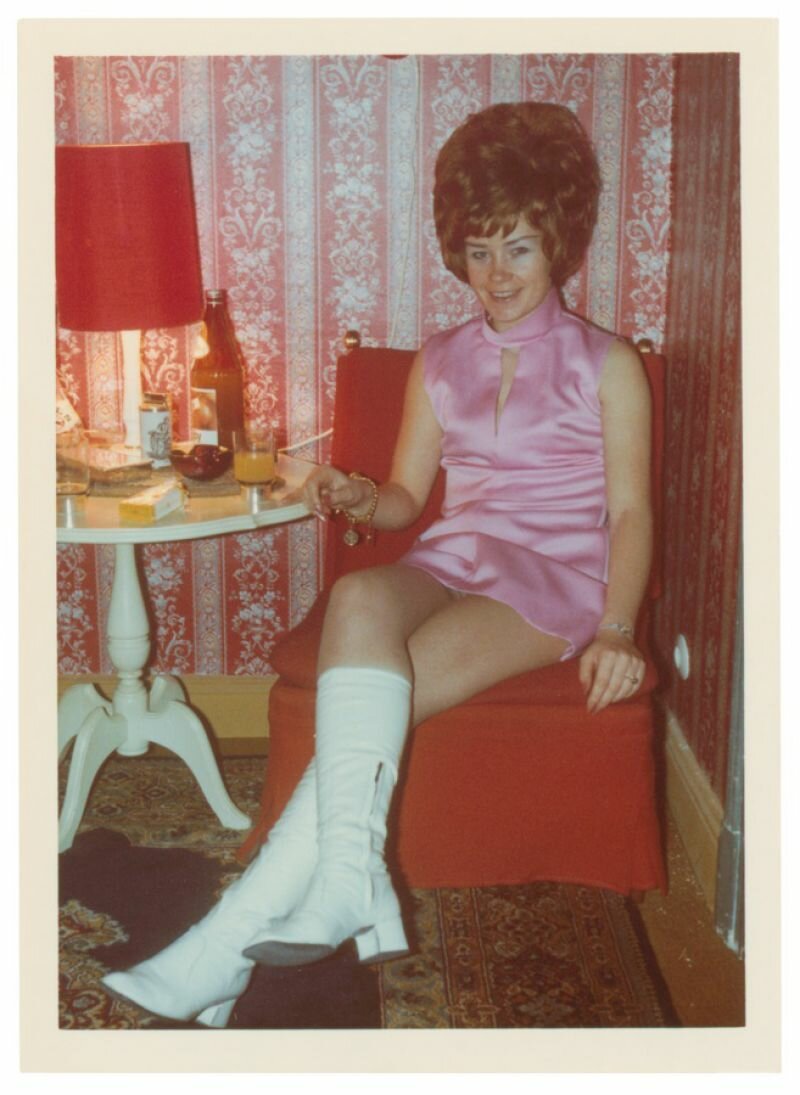

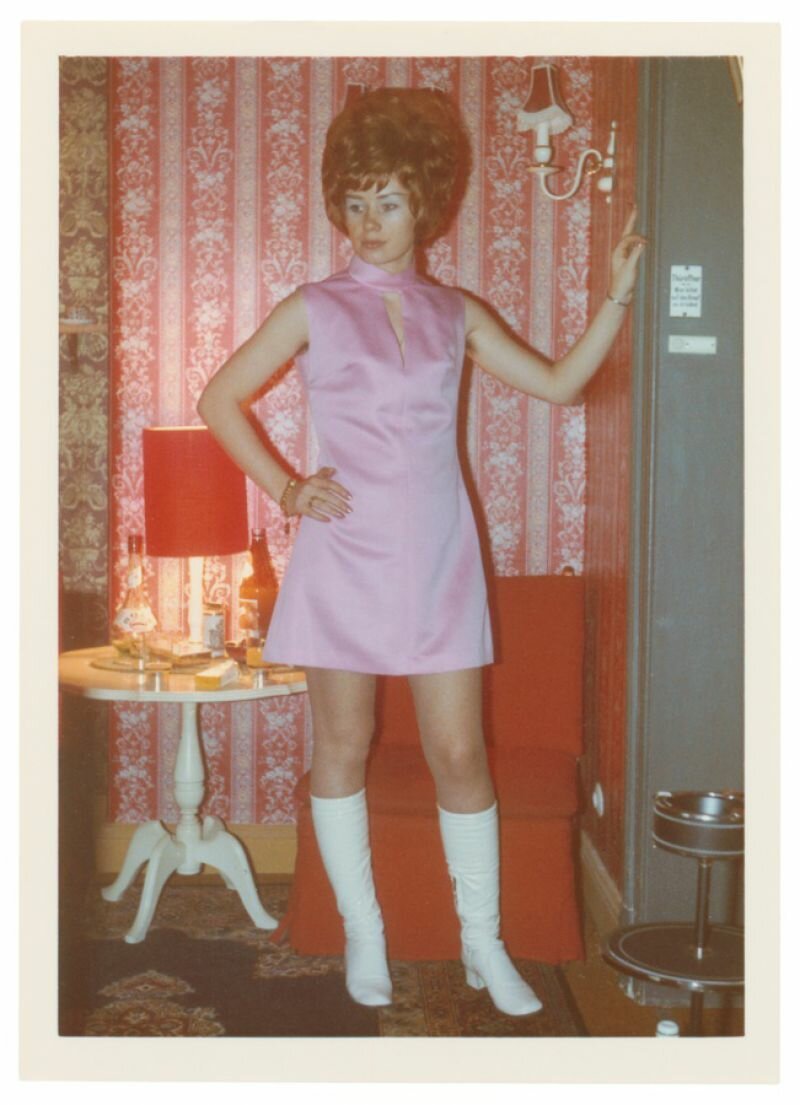

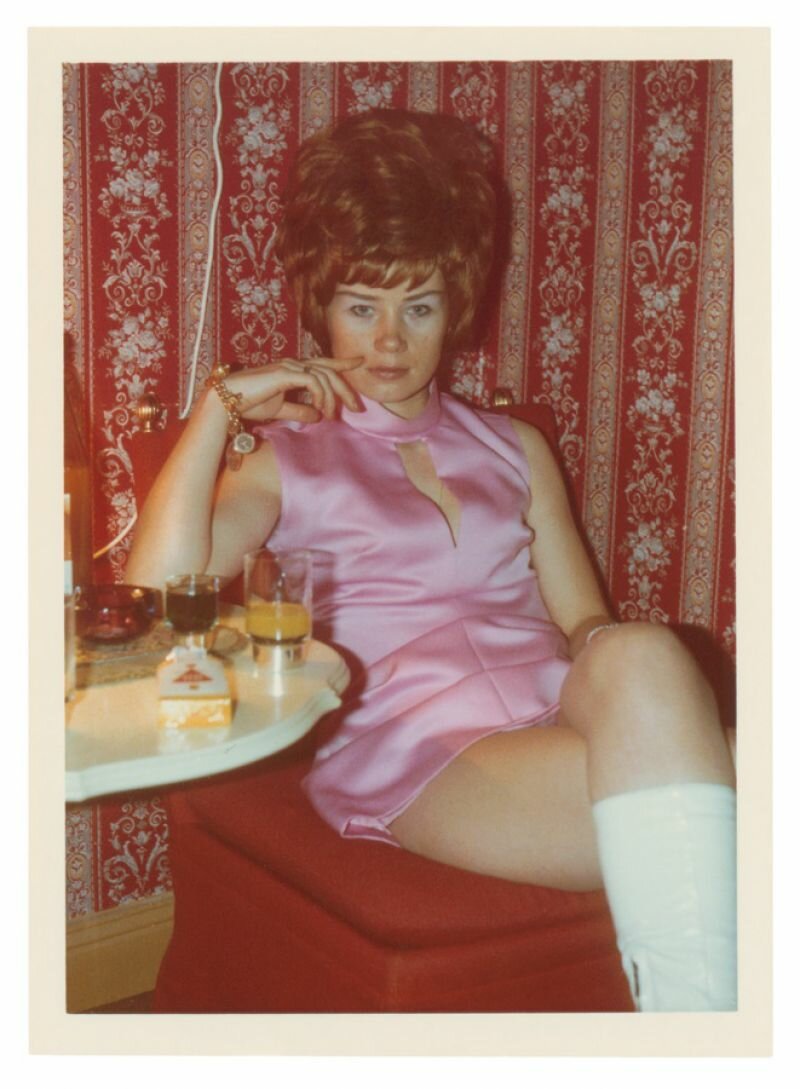

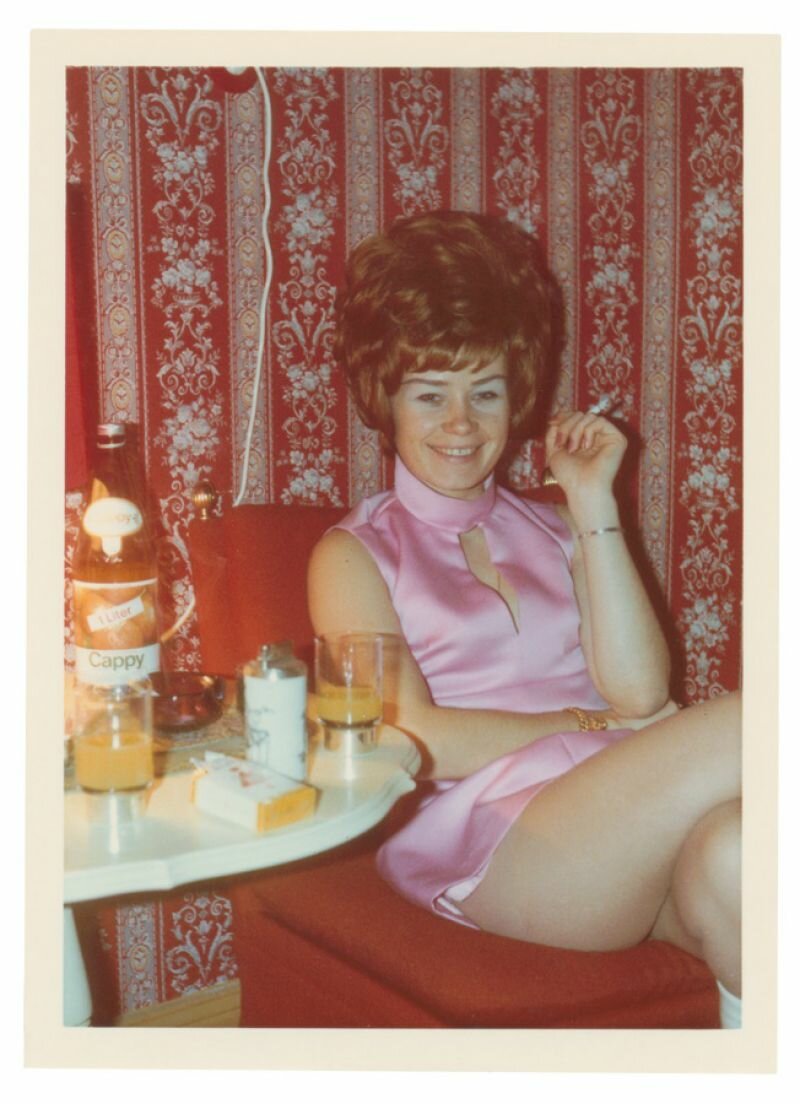

The first note of Günther is written on Friday, the 9th of January 1970: ‘Fr. 9.1.1970: haren getont ’ (hair dyed), and in the next series of portrets we see Margret with a modern, red haircut with bangs. Günther transforms his secretary into a sophisticated woman. He dresses her, buys her stockings and jewellery and takes a lot of pictures. This affair follows a few clichés. As seen on the photos, Margret actually wears glasses, but prefers not to in her role as a seductive lady. Günther takes her to a modern world of spas, casinos and castle dinners. The love is allowed to be celebrated. Margret poses in an orange bathroom, next to flowers in a vase, against the decor of the park-like gardens that surround the hotels. She smokes often and with pleasure, because nothing is better than a cigarette after love making.

He takes pictures of his love during the rendez-vous, before and after sex. While time passes by, the notes get longer and the details get both dry and juicy.

In the first lang note, typed on a page from a calendar with a big eight on it, ‘dienstag, Maria Geburt’, Günther describes the next scene:

Monday 7.9.1970: At lunch Leni (Günthers wife) says to Margret: Madame, you are of lowly character, you're disrupting a good marriage.

Dinsdag 8.9.1970: Around 10 a clock Margret says to me: You let this insult from your wife against me pass? No more sex, you can jump on your own wife. Whatever you do, don't think you can jump on me anymore!

Later, my wife has to apologize to her at lunch on 8.9.1970

That afternoon they go upstairs again to make love and the note ends with:

Teufelsalat gegessen.

Alles in Ordnung wiederum.

The sexual revolution is happening right now and yet old conventions and principles of power determine the position of the man and women. The boss and his young secretary. Günther’s Leni knows about the affair, she endures it and humiliates herself. Marget is his lover, overflows with confidence and plays it high. Her husband knows nothing about the affair en when the boss takes his secretary home after a business trip or meeting, they even drink together. He calls her Zini and she calls him Schnaggel. In January 1970, she takes her birth control and Günther saves the empty strip. He also saves hairs, pieces of fingernails, a towel with a stain of blood, bills and receipts of bought clothes. They seem to have an obsessive relationship.

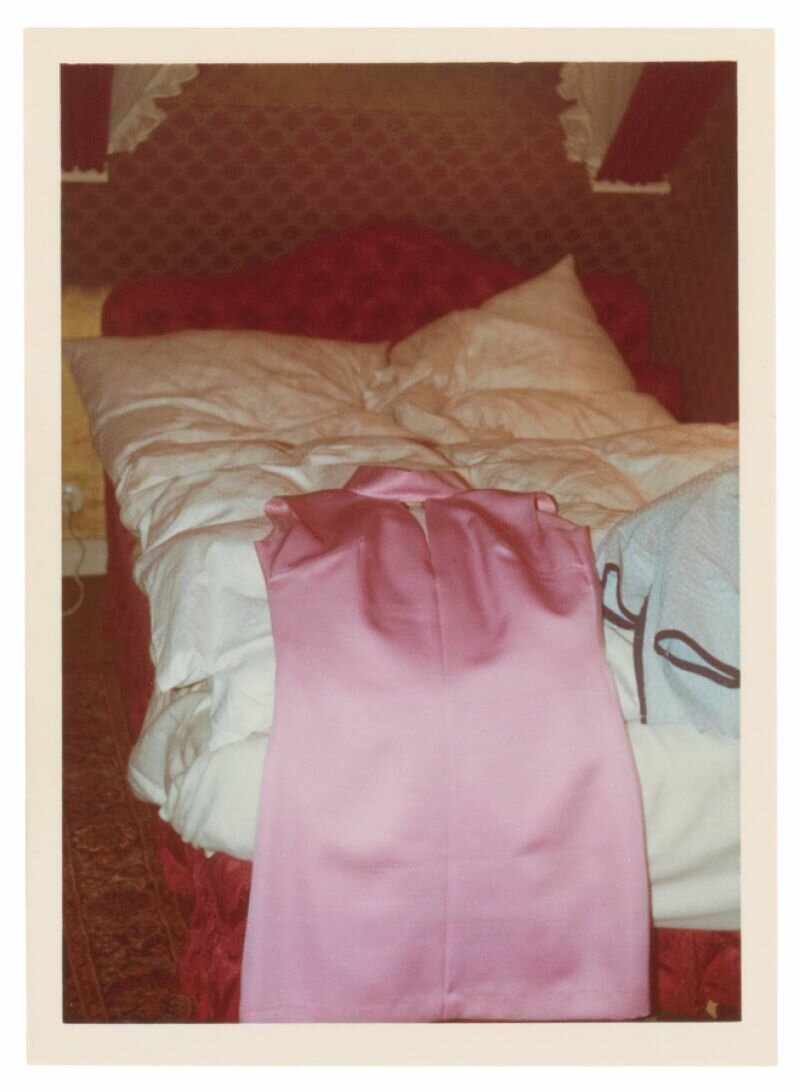

In 1970, they go on a trip twice together. The looks are typical of the 70’s, with high hairstyles, miniskirts and innocent poses. The most revealing photo is a naked Margret who dries herself with a towel in the bathroom, which can’t be more like home. Or a photo from her dress, lying on the bed. Each photo is perfect, love makes good photographers and there is nothing better than a lovers gaze.

Only in words, their affair could be more explicit. During one of the trips, Günther makes a list of all the times they made love.

Wednesday 12 Aug. 1970: 17 18.15 1x

Beginning of her period (tampon) Initiation party anyways

Tuesday 18 Aug. 1970: 15.15 -15. 20

Yellow chair in front of the aquarium (sitting) 1x

Wednesday 2 Sept. 1970: 17. 05-18.00 1x

With beautiful music, resting afterwards

And so forward..

In timed, his descriptions get longer rand more explicit. While the love gets more complicated, there are less photos and more words.

Monday 2 Nov. 1970

At 1 am I played with her pussy and clitoris until she came. At 5 pm we went upstairs again. White-blue dress and white boots. After a drink, she had taken of her dress and put on the brown with the messing buttons I gave her. It fit perfectly. Took photos of the front of the dress and then of her in the brown dress at the bar. Then to bed. Both naked. Licked her two breasts, caressed her bushy cunthairs and her clitoris until she came on top of me. First a normal position, then a special one. It was amazing.

When the couple is staying in Bad Eims, Margret's husband, Lothar, causes a deadly accident with a 70 year old bicyclist, as we can read in the typed notes, but the trip doesn't end there and no further information is typed.

And then, suddenly, there is Giesela, and Ursula. Because Margret wants to prevent any suspicion, she requests that Günther goes on dates with the women. And with the same pleasure, Günther describes the love making with Giesela. After their diner in Grill-restaurant Goldener Pflug (receipt saved), he takes her with him, fucks her and calls her sexually starving. He describes Margret as extremely jealous:

Fraulein Ursula, 21th birthday in Nov. 1970, big and skinny, she looks really good. White boots, green dress, black hair.

Margret starts to panic.

In a note from Günther we read: Margret immediately said, whether she had not seen her: You are in love, don’t go through with her, Günther, please don’t go through with her, not with her. I was unmoved and Margret stepped out of the car in de Subbelratherstrasse.

Günther drives on and returns to Ursula. The last line in this long note: In that same night Margret fights with her husband and asks for a divorce.

In the next note he picks up Margret at her house and they make love: Sie war wirklich so wie ich mir eine verliebte Frau wünsche.

His last note is a long description of their love making.

It is an unfinished report, fragmented, by which you have to read between the lines and fill up the empty spaces. What makes this man write notes and report his affair so precisely? Perhaps he wanted to contain the love and relive the sensation. He wanted to give his love a platform. He wants to confirm his control over the situation, to master the affair. Does he type his reports in the living room, accompanied by his wife? At work? And where does he keep the suitcase with the evidence? The suitcase was found at home. In the attic? And his wife did not once throw away the whole love account. She swallows it, again and again. He must be the kind of man that has that much power over his wife that she just lets it happen. After all, the feminist revolution had only just begun.

Love and power share an inner bond, even in the times of the sexual revolution.

Margret, Chronik einer affäre, Mai 1969 bis Dezember 1970. Uitgever Walther Köning, Keulen, 2012.