In 2002, I received a New Year’s greeting from the Amsterdam Archive in which they announced a grand exhibition about city maps from across the centuries. I imagined making the most current map of Amsterdam. A living map. Formed by use of the city, using the most modern technology. While traversing the streets, the users of the city would create a trail, as though the streets were formed by the pedestrians the way that roaming cows form paths in the mountains.

Visible trails. This could be made possible by giving a number of pedestrians a GPS system and sending their information to a central computer. This computer would, in real time, sketch their routes on a blank screen. The more movement and the more users, the more visible Amsterdam would become. Different types of users would be appointed different colours, so that one could see the difference in how the automobile driver, cyclist and pedestrian uses the city.

I called the Municipal Archive and spoke with Ludger Smit. He made the great suggestion of attaching equipment to ducks so that canals too would become visualised. I understood that he understood where I was going.

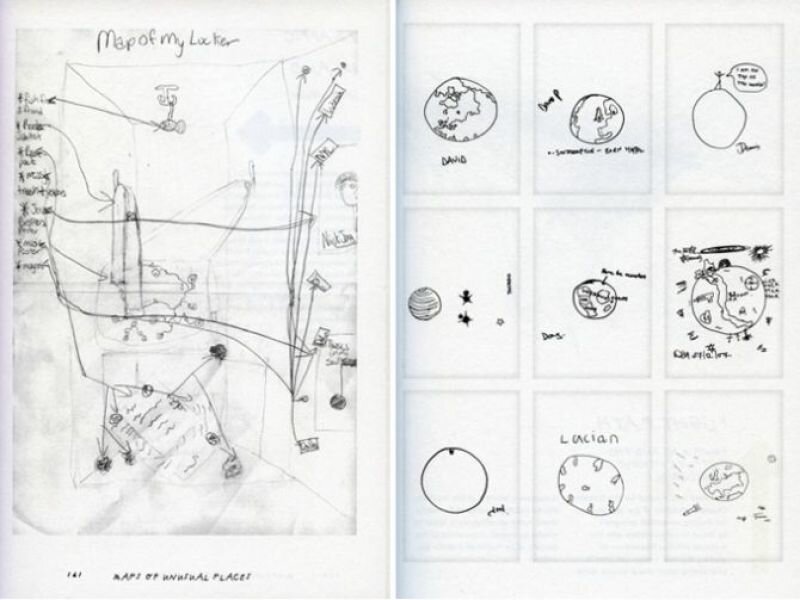

Every Amsterdammer has, as I imagine, an invisible map of the city in their head. The way they move throughout the city and the choices that he makes while doing so are determined by this mental map.

When different users leave their traces in different colours, the viewer will be able to see how individual the map of Amsterdam can be. The favourite routes of a bike courier differ immensely from that of a taxi driver. The mode of transportation, the customer’s request and the person’s mental map will shape the trail that he leaves behind.

I imagine that trails older than a few days will erase themselves. In this way, a constantly changing, very current, but also extremely subjective map of Amsterdam will be created.

The data will be stored and will result in a film at the end of the project. In the best case scenario, the film will also provide a time frame that will indirectly make visible large events and crowds, like a marathon or a royal wedding.

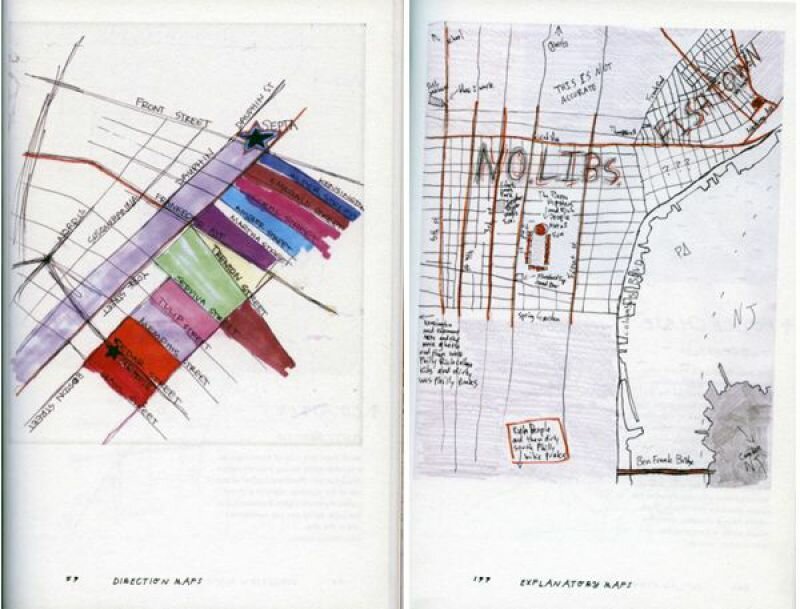

A completely different option is to use this installation to undermine the power of the cartographer. It would be possible to invite a number of people to use this drawing machine to create their own map. One could use the GPS system to trace the name of their loved one by cycling through certain streets. Another might attempt to draw the official border of the Vondelpark (regardless of having to brave fences and bushes in the process), Another might decide to walk across the same small path hundreds of time, so that it appears on the map as the most important route in the whole of Amsterdam. However, as more people make use of the GPS tracking system, it will start becoming more recognizable as an objective map.

To begin my project, I headed to the Stedelijk Museum’s library to research what other artists have done using maps and charts. What I found most stimulating was a work by Kim Dingle. She had asked teenagers to draw a map of America from their imagination. This resulted in bizarre splotches that she arranged in a rhythmic pattern on a white plane. It looked good as a reproduction. The teenagers were anonymous, yet I could see straight into their minds. It makes one think of the possibility of creating a psychological test based on the analysis of their internal map. You could ask someone: make a realistic map of the terrain that you see as your living environment. A domestic type will draw a map of their house; an adventurous type would draw the whole world. The discrepancies in proportion say a lot about someone’s personality, Reading a palm and reading a map in one.

I also found Morit Kung’s book Orbis Terrarum to be fantastic, it contains an extremely rich content. The combination of historical maps and contemporary art is, of course, very relevant to my own projects, and I have to admit that the contemporary works motivate me to study the old maps in more detail. Enjoying these objects is an acquired taste. There are, of course, errors in the maps, but they only make their further accuracy all the more impressive. God knows how they were capable of creating a reasonably accurate depiction of the world back then. Without satellite photos... was this all just done with the aid of a compass and the sun?

I also attended an event organised by the hiking club Nemo; a lecture by John Eberhardt, head of the publishing company Buijten en Schipperheijn. Eberhardt creates inventories of routes, and so cartography has become his occupation. Cartography is a Dutch invention. A man named Jacob van Deventer was ordered by the king to draw 250 city maps in 30 years by securing a chain between his legs and counting his steps. The maps are still remarkably accurate.

Eberhardt admitted to mapping stretches of neglected paths as functioning cycle paths, in the hopes that they would end up actually becoming cycle paths. In some cases his plan worked: sometimes so many complaints were issued to the municipality that something really must be done about that bike path. As I heard the cartographer speak about his map, it became apparent that The Map, with its intrinsic air of objectivity and authority, is in fact determined by the subjective choices of the map’s maker and the constraints of technology, time, and money. What I had also never realised is that freedom of press is equally applicable to the publishers of maps. Eberhardt even spoke of the ‘dissident cartographer,’ which I find in itself a beautiful title. The world that is mapped is constantly changing. Each ‘layer’ of the map changes in its own tempo. The difference in the tempo of movement of continents and of migratory birds is immense, and the changes in buildings and plant growth are wedged in between there. His ideal map is one that is in constant movement, which is always changing. My idea of the most current map is very similar. The map itself draws this constant changing of the map.

Reading a map is a form of virtual reality. A model of reality can also change reality (think of the cycle path). By viewing a map through a new perspective, one can discover things that even the cartographer missed. A smart archaeologist, for example, found that all the dolmens of Drenthe are aligned in an exact straight line. The maker of the map had drawn it, but had overlooked it. A map is, then, a reality within itself, where new discoveries are always possible.

A map is also a Utopia. Each map and each user holds his own Utopia. A map for fishermen, hikers, drivers, or geologists each manifests another imagined world. Each map will allow you to enter a landscape with a different experience.